Overview:

South Dallas is facing a transformative moment with the 2026 World Cup at Fair Park, restoration of Forest Theater, and state legislation accelerating development timelines. Developer Scottie Smith, II believes that the neighborhood can reclaim its future through a proposed Public Improvement District (PID), which could generate approximately $225,000 annually to support lighting improvements, rebuild sidewalks, increase public safety response, stabilize legacy small businesses, and transform commercial corridors into walkable destinations. However, the previous PID struggled due to a disconnect between leadership and the community, so the new plan includes significant guardrails and will not advance without resident input.

South Dallas is entering one of the most transformative and high-stakes moments in its modern history. With the 2026 World Cup at Fair Park on the horizon, the restoration of the historic Forest Theater underway, and state legislation accelerating development timelines, the neighborhood faces a critical question that DW has explored extensively through its investigative series: Who owns South Dallas, and who will own its future?

Developer, broker, and community partner Scottie Smith, II believes that the neighborhood can reclaim that future — but only if residents control the financial tools that shape redevelopment. He currently serves as the chairperson for the South Dallas Fair Park Area Plan Taskforce. And for Smith, one of the most powerful mechanisms available is the proposed Public Improvement District, or PID, a tool he says could keep investment dollars circulating within the community they’re meant to support.

In a wide-ranging conversation with Dallas Weekly, Smith shared his journey, the urgent opportunities ahead, and the lessons that must guide South Dallas if it hopes to build development that protects, not displaces, its residents.

Sign up for our free newsletter to receive original, on-the-ground reports from the DFW area three times per week!

A Wrong Turn, and a Vision for Home

Smith’s introduction to South Dallas wasn’t strategic — it was accidental. “I made a wrong turn off Malcolm X,” he recalled. “But when I stepped out on that land, it reminded me of home. And the area was us.” What began as a few development projects quickly evolved into a broader recognition that South Dallas was missing critical elements of a healthy community: reliable lighting, infrastructure, walkable corridors, and places to live, work, and play without leaving the neighborhood.

His work in the area deepened with the Jefferies-Meyers Project, an example of intentional, Black-led investment in one of the city’s most historic — and vulnerable — neighborhoods, and a model South Dallas hasn’t seen at this scale since the era of Honorable Diane Ragsdale. For decades, Ragsdale defined what it meant to build from within South Dallas; grounded in Wheatley Place and rising through volunteer activism, city-council leadership, and the founding of the Inner-City Community Development Corporation, she reshaped housing and land use around Spring Avenue and Dolphin Heights while insisting that real change must be led by residents, not imposed on them. Today, Scottie Smith II picks up that mantle, echoing Ragsdale’s commitment to reclaiming land, resources and power so that economic uplift happens for the people who already call this place home. In doing so, he not only connects to her legacy — he demonstrates that intentional, resident-centered development remains possible when it is rooted in community agency.

What a PID Really Means for South Dallas

Many residents know what taxes are, but fewer understand what distinguishes a PID (Public Improvement District) from other funding tools. Smith describes it plainly:

“A PID is group economics at its purest. Property owners agree to self-assess, and that money — by law — stays within the PID boundary and must be spent according to the community’s priorities.”

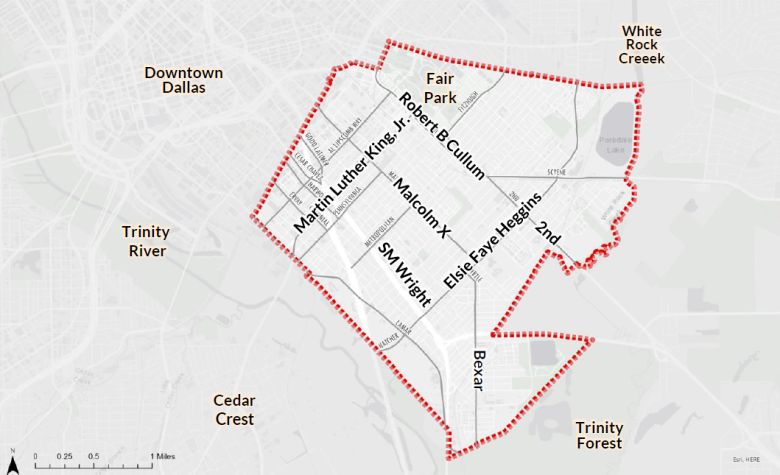

Photo Credit: City of Dallas Planning & Development

Photo Credit: City of Dallas Planning & Development

Unlike general tax revenues that get dispersed citywide, PID funds stay concentrated in one neighborhood. Smith points to the Downtown Dallas Inc. PID as an example of what’s possible: increased residential foot traffic, new businesses, public events, beautified corridors, improved lighting, and even measurable decreases in crime. “If downtown can do it,” he said, “South Dallas can too — with our own flavor and culture.”

Photo Credit: City of Dallas Economic Development, Downtown Dallas Improvement District

Photo Credit: City of Dallas Economic Development, Downtown Dallas Improvement District

Smith believes that with $1.5 billion in development projected for South Dallas over the coming years, a PID could generate approximately $225,000 annually, money that would support lighting improvements along MLK and Malcolm X, rebuild sidewalks, increase public safety response, stabilize legacy small businesses, and transform commercial corridors into walkable destinations.

Learning from the Past — and Not Repeating It

South Dallas previously had a PID, and it struggled. The South Dallas Fair Park Area PID was previously managed by South Side Quarter Development Corporation, and according to city of Dallas records, their management term is up December 2026. Smith did not hesitate to acknowledge that history. “There was a lapse in management,” he explained. “A disconnect between leadership and the community.” It’s a pattern DW has seen repeatedly in South Dallas planning efforts, from Fair Park conservancy oversight to city-led development projects that have failed to center residents.

Unlike previous city planning efforts that often unveiled glossy visions without meaningful community leadership, the new South Dallas/Fair Park Area Plan—adopted by City Council on June 25, 2025—was shaped through more than four years of on-the-ground engagement, including over 100 community events, workshops, neighborhood tours, youth meetings, and stakeholder sessions, resulting in a plan that not only reflects resident voices but also establishes clear metrics, priority projects, and accountability measures designed to ensure that investment finally benefits the people who live in South Dallas.

To avoid repeating those mistakes, the new PID plan includes significant guardrails. Management would be overseen by Forest Forward, an organization rooted in the community with a proven track record of raising and deploying capital responsibly.

Smith emphasized repeatedly that the PID will not advance without resident input.

“This isn’t my thing — it’s an us thing.” – Scottie Smith, II

Whether residents support the PID or oppose parts of it, he wants them in the room. A series of upcoming meetings, listed at SunnySouthDallas.org, will offer opportunities for residents to sign petitions, raise concerns, propose changes, and fully understand the boundaries and goals of the district. “If something doesn’t make sense, tell me,” he said. “I don’t have all the answers — just a lot of ideas. The collective community is where we win.”

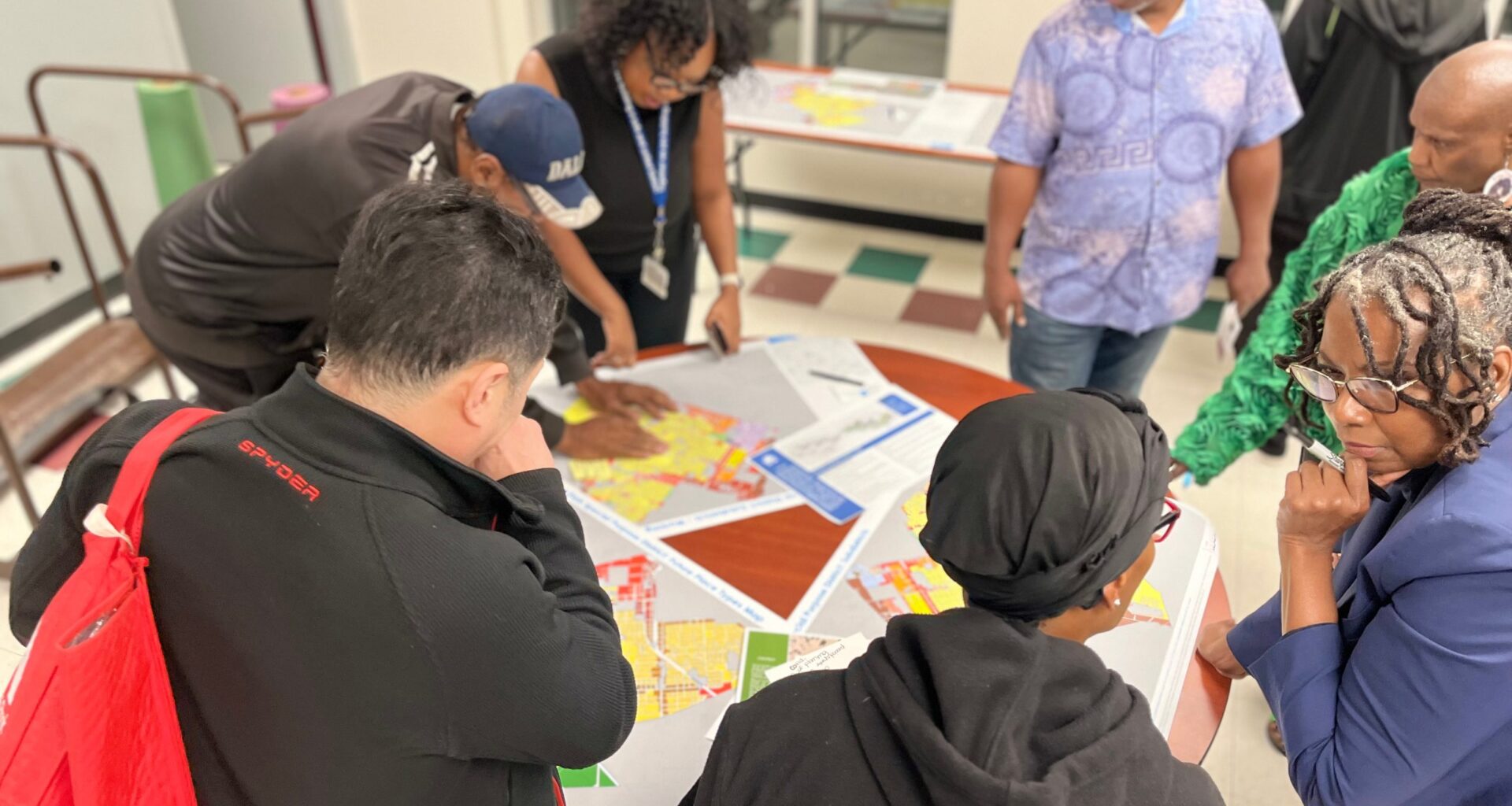

Community Members at the Nov 13th SDFP Public Meeting. Photo Credit: Sisi Encarnacion

Community Members at the Nov 13th SDFP Public Meeting. Photo Credit: Sisi Encarnacion

The next public meeting will be December 9th from 6 -7:30 pm at the MLK Jr. Recreation Center.

A Message to a Rightfully Skeptical Community

In the closing moments of the interview, Smith addressed the skepticism many South Dallas residents feel toward new initiatives. “We’ve been used and abused for far too long,” he said. “Plans get announced with no funding. Promises get made without follow-through.” He referenced the last plan for the South Dallas area that full of potential, but lacking the capital mechanism needed to deliver results.

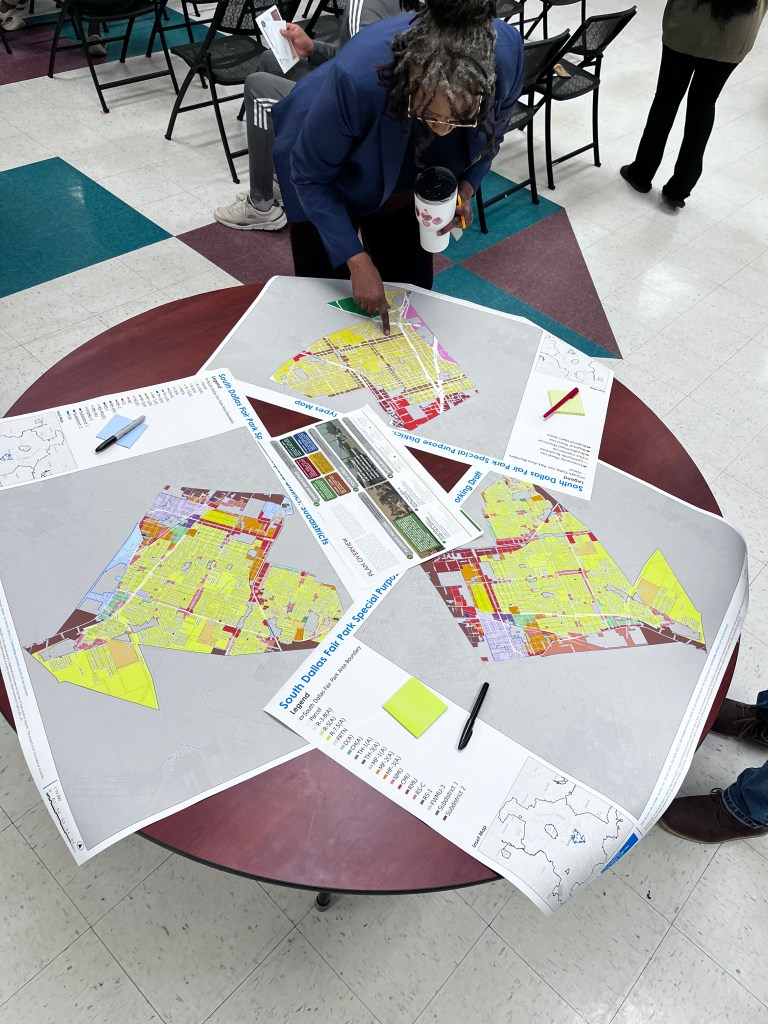

Community Members viewing South Dallas Fair Park maps at the Nov 13th SDFP Public Meeting. Photo Credit: Sisi Encarnacion

Community Members viewing South Dallas Fair Park maps at the Nov 13th SDFP Public Meeting. Photo Credit: Sisi Encarnacion

“This PID is not the solution to everything,” Smith said. “But it’s a tool — one tool in a larger strategy for how we rebuild South Dallas for us.” He added, “Everything I said I would do for South Dallas, I’ve done. I stay until it’s finished. This PID is another commitment to what the community has said it wants.”

A South Dallas Built by South Dallas

Smith imagines a South Dallas where residents can start their morning at a local barbershop, walk to brunch on MLK, attend a performance at Forest Theater, and return home safely — a neighborhood with the infrastructure, culture, and economic stability its residents have fought for over generations.

Through the “Who Owns South Dallas?” series, Dallas Weekly has tracked the long fight for ownership, autonomy, and equity in the neighborhood. Smith’s efforts — from Jefferies-Meyers to the proposed PID — represent a continuation of the community-led development championed decades ago by leaders and demanded today by residents seeking a future rooted in dignity, safety, and belonging. The South Dallas–Fair Park area, a historically Black neighborhood with deep cultural roots, has long possessed the capacity to thrive alongside Dallas’ most affluent districts; its distinct identity and steadfast community pride reveal what could be possible if meaningful investment were guided by the very residents who have sustained it for generations.

As South Dallas stands at a crossroads, the question remains: Will the neighborhood shape the change ahead, or be swept away by it? Smith believes the answer depends on whether residents decide to take hold of the tools available — and build the South Dallas they deserve.

Dallas Weekly will continue to cover every step of this process.

Support Our Work

With the support of readers like you, we can continue to create thoughtfully researched articles for a more informed and connected community.

Related