OLD IRVING PARK — Plans to bring a 606-style rails-to-trails project to the Far Northwest Side have gained support from elected officials, but many say anti-gentrification legislation needs to be put in place before the project comes to fruition.

The proposed Crosstown Trail would stretch from near West Montrose and North Knox avenues in the north to near West Cortland Street and North Kilbourn Avenue in the south. The 3.2-mile trail would follow a current Union Pacific freight line that travels alongside North Kenton Avenue. The Crosstown would serve Old Irving Park, Irving Park, Portage Park, Kilbourn Park, Belmont Cragin and Hermosa and would help connect The 606 to the North Branch Trail and proposed Weber Spur trail.

While there has been talk about turning the old Kenton rail line into a pedestrian trail for years, Old Irving Park neighbors George Witchek and Jim Franke formed the nonprofit Friends of the Crosstown Trail this year.

The group has been presenting the project at neighborhood meetings, and in June they launched a petition that has gained more than 4,500 signatures. Ald. Jessie Fuentes (26th) and Cook County Commissioner Jessica Vasquez held a virtual town hall Thursday to discuss the trail. Almost 300 people attended.

Vasquez called the town call “the beginning of the conversation around the vision for the Crosstown Trail.”

“A project like this is exciting when it’s done well, and a step in the right direction is having conversations like this,” she said.

A map showing the proposed Crosstown Trail route. Credit: Provided by Friends of the Crosstown Trail/ Block Club Chicago

A map showing the proposed Crosstown Trail route. Credit: Provided by Friends of the Crosstown Trail/ Block Club Chicago

Development Without Displacement

Ben Helphand, founder and president of Friends of Bloomingdale Trail, spoke during the meeting and said the Blooomingdale Trail took well over a decade to bring to life. The trail turned 10 in June and has already seen more than 10 million users.

Fuentes said she remembers all the “excitement” when the Bloomingdale Trail opened, and she remembers the displacement.

A 2016 study from DePaul University’s Institute for Housing Studies found that, along the western part of the Bloomingdale Trail, housing prices went up 48.2 percent after construction on the trail began. Between 2013 and 2018, the area near the Bloomingdale Trail lost almost 60 percent of its two- to six-flat buildings, according to the Institute for Housing Studies.

The two- and three-flats near the trail were demolished to make way for multimillion-dollar single-family homes, Fuentes said.

Fuentes said elected officials should start thinking about what kinds of policies can be passed to protect against gentrification now, in the early stages of the Crosstown Trail planning.

“We should not shy away from these types of developments, but we should make sure that there’s legislation in place,” Fuentes said.

Marco Chaidez, the community and economic development manager with the Northwest Side Community Development Corporation, said creating a community land trust, like the Here to Stay land trust in Logan Square, can reduce displacement. Rent control and giving tenants “the right of refusal,” which means renters have the first opportunity to buy their building when it goes on sale, are also tools that can reduce gentrification, Chaidez said.

In December, the City Council approved the Northwest Side Housing Preservation Ordinance, which charges developers when they tear down single-family homes and multi-unit buildings in parts of Hermosa, Logan Square, Avondale, West Town and Humboldt Park.

The fees from the demolition surcharge go to the Chicago Housing Trust and Here To Stay. The ordinance also gives tenants the right of refusal.

Jeanette Hernandez, a lifelong Logan Square resident, said that if the proposed trail is constructed, she would like to see controls put on property taxes to ensure current residents aren’t priced out.

“The people who live in these neighborhoods should be the ones benefiting and enjoying these new amenities,” Hernandez said.

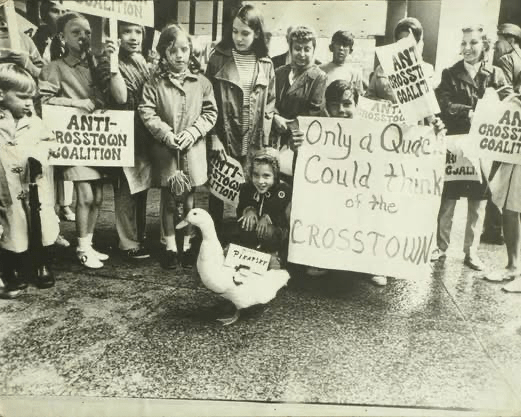

A photo of an anti-Crosstown Expressway protest. Credit: Provided by Debbie Timko/ Block Club Chicago

A photo of an anti-Crosstown Expressway protest. Credit: Provided by Debbie Timko/ Block Club Chicago

A Long Trail Ahead

Neighbors and elected officials have been talking about transforming the Kenton Avenue rail line for more than six decades.

In the 1960s, then-Mayor Richard J. Daley wanted to create a 22-mile Crosstown Expressway that would run from the Kennedy-Edens junction south to the Eisenhower Expressway, then to about 75th Street, where it would have turned east and run to the Dan Ryan Expressway, according to the Tribune.

The goal was to reduce congestion and divert traffic from Downtown, but the Illinois Department of Transportation estimated the Crosstown would displace 33,177 residents and 2,103 businesses, according to the Tribune.

Neighbors living within the Crosstown’s proposed footprint organized against the project, and it was killed in 1979.

Franke said the Crosstown’s history shows “the community can do big things.”

However, he knows the project has a long road ahead.

“I believe it’s fair to say that 10 years and several tens of millions of dollars is pretty optimistic,” Franke said.

Franke said another complication is that while the Union Pacific rail line along Kenton Avenue is “underutilized,” it is still active.

Witchek said Friends of the Crosstown Trail is still in the process of getting the word out about the project. He said the group met with neighbors, representatives from the city’s Department of Transportation and local elected officials over the summer.

“We need to make the Crosstown Trail a household name,” Witchek said. “It’s amazing that over 250 people are here tonight, but we know this trail could impact hundreds of thousands of people, and it’s really important that everybody is informed on what we’re trying to do here.”

Vasquez said Thursday’s town hall was the first of many meetings.

You can learn more about the proposed Crosstown Trail here. You can sign up to volunteer with Friends of the Crosstown Trail here.

Listen to the Block Club Chicago podcast: