PHOENIX – Marquette King boomed punts downfield, then celebrated with moves tailored to his opposition, carving out a distinct persona at a position known for anonymity.

That persona may also be the reason he has spent the last several years out of the NFL.

In 2012, King signed with the Oakland Raiders as an undrafted free agent out of Fort Valley (Ga.) State, and after impressing during the preseason while playing in place of injured veteran Shane Lechler, spent his first year stashed on injured reserve. When King won the job in 2013, he became just the fifth Black punter in NFL history.

From then on, he shone on one of the NFL’s glamour franchises — and a franchise known for rostering players who went against the grain — in a city with deep-rooted Black history.

King’s cousin, Greg Rhymes, who grew up with King in Macon, Ga., would attend games and think to himself, “That’s my family right there.” He’d take photos with fans wearing King’s No. 7 jersey and share them with his cousin.

“It was all cool,” Rhymes said. “The more famous he got, I actually started to see a lot of people wearing them.”

There weren’t many better fits for a stylish, exuberant Black punter from a Historically Black College than Oakland.

“If Marshawn Lynch was a punter, that would be Marquette King,” said Ameer Loggins, an Oakland-area native and a doctoral candidate in the African American Studies department at Cal Berkeley. “That kind of energy resonated with folks in Oakland. And the way in which (King) acted out his Blackness on the field, it was able to make the punter look like a football player, as opposed to a specialist that happens to be in a football uniform.”

King loved being a Raider. He has the team’s logo tattooed on his leg. He spent his first five seasons playing alongside kicker Sebastian Janikowski, a Raider for 17 years, and succeeded Lechler, who donned silver and black for 13 years.

“I thought that was going to be me,” King said over lunch on a rainy afternoon at the Arizona Biltmore hotel.

He didn’t care that there was an NFL game in nearby Glendale the night before. He doesn’t regularly watch games or follow much of what’s going on. After all, the league left him behind years ago

A second-team All-Pro selection in 2016, King was one of football’s best punters for a half-decade, leading the league in punt average in 2013 and in punt yards in 2014. But at a position where many play into their mid-to-late 30s — six players 34 or older have punted for NFL teams in 2025 — King played his last game at 29. And he thinks he knows why.

“I’m definitely blackballed,” he said. “I’m definitely better than over half the punters still playing. That’s just what it is.”

After King twice pinned the Denver Broncos inside their own 3-yard line in a 30-20 Raiders win in November 2016, he got a call from Deion Sanders. Then working as an analyst for NFL Media, the Hall of Fame cornerback and future coach dialed up the punter for a postgame segment.

“We don’t just like your punting ability,” Sanders told King. “We like the flavor that you bring to the table when you punt the ball.”

That flavor came in many forms. A 2017 NFL Films segment declared King had “the personality to match his proficiency.”

“I’m not a punter,” he told NFL Films. “I’m an athlete who punts.”

Punting provided an outlet for expression. He was active on social media and even more active on the field after a successful leg swing. He mimicked Ray Lewis’ celebration against the Baltimore Ravens and hit the dab against Cam Newton’s Carolina Panthers. He went for a horseback ride against the Broncos and performed Shawne Merriman’s “Lights Out” sack dance against the Chargers.

Punters don’t typically ink deals with Nike, Amazon and Facebook. But at a time when players were just beginning to understand their ability to profit from their name and likeness, King was a pioneer on social media, his former agent, Wynn Silberman, said.

“All of a sudden, these deals started running across our desk,” Silberman said.

Jack Del Rio, the Raiders’ head coach from 2015 to ’17, saw King as a passionate kicker who played with an edge. His only gripe came when King incurred personal foul penalties that hurt the team. King was fined three times for unsportsmanlike conduct: once for a horse-collar tackle, another time for using a penalty flag as a prop, and again for throwing the ball at an opponent.

“I talked with him myself about needing to be in charge of emotions,” Del Rio said. “It was something that was coached on and we talked about. I was one that was in his corner. There was so much talent there. I believed that we could channel that, but I know patience ran out once I wasn’t there.”

King signed a five-year, $16.5 million contract with Oakland in February 2016, seemingly cementing his place in the Raiders’ long-term plans. “He’s someone who developed for us and gave us a real weapon,” Del Rio said.

But after Del Rio was fired following the 2017 season, things changed quickly. Jon Gruden returned to Oakland after leading the Tampa Bay Buccaneers to a Super Bowl victory ahead of a nine-year stint on “Monday Night Football.” Shortly after the hiring, King appeared on NFL Network — wearing a crown and robe while holding a scepter— and jokingly referred to his new coach as “the guy from ‘Monday Night Football.’” Then, during the 2018 scouting combine, Gruden disparaged King’s holding duties on the team’s field goal unit.

King heard Gruden wasn’t fond of him, so he picked up gifts: Snickers for Gruden and bottles of limoncello for new special teams coordinator Rich Bisaccia. The day King brought the gifts to the facility, he was released.

“I still have those two bottles of limoncello in my closet,” Silberman said.

When reached for comment for this story, Gruden told The Athletic, “I never met Marquette King.” Gruden, who resigned in 2021 after it was revealed he used racist, homophobic and sexist language in emails with league personnel, told outlets King’s release was salary-cap related.

King remains frustrated that he didn’t receive an explanation from Gruden — or anyone. He admits the NFL Network interview was “a little extra,” but he maintains that, had Gruden or someone else in the organization told him to shut up and punt, “I would have collected my check and just did my s—.”

“All they had to do was just tell me,” King said. “But some people aren’t secure or confident enough to be able to do that.”

For King, the release showed him the NFL was not a true meritocracy. “That’s when I realized politics was a thing,” he said. There were rumors he was a toxic teammate, that the penalties were his undoing and that the locker room soured on him because he trolled teammate Michael Crabtree by snapping a photo at the Pro Bowl with Broncos cornerback Aqib Talib, who infamously snatched Crabtree’s chain during the 2016 season finale.

King had another explanation.

“I just had too much personality,” he said. “I got a lot of personality, and people just don’t know how to handle that, or people who are insecure with who they are — (if) they don’t feel like they can have some type of control over how you move or what you do, then it’s an issue.”

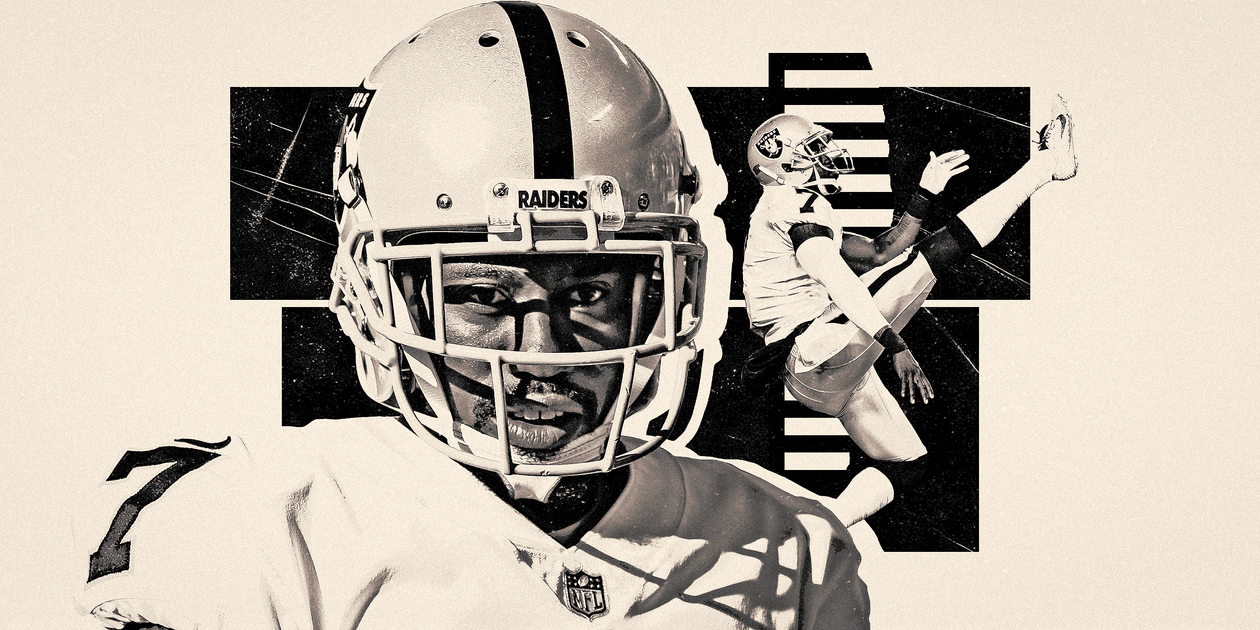

Marquette King was known as much for his exuberant celebrations as he was for his booming punts. (Doug Pensinger / Getty Images)

Following King’s release from the Raiders, inquiring teams — there were several — did their due diligence. Over the years, in conversations with people around the league, Silberman would field questions about his client.

“One of the running jokes was, ‘Will your guy ever behave?’” Silberman said.

When King needed a new NFL home in 2018, it was Silberman’s job to explain that King’s unemployment wasn’t injury- or performance-related.

“There was an implication there was a personality conflict with the new coach,” Silberman said. “And that’s all you had to say.”

King signed with the Broncos a week after his release from Oakland, but he didn’t last a full season in Denver before being placed on injured reserve with an abductor issue. He was eventually released after coming to an injury settlement with the team.

As he tried to find another NFL job, perception affected reality. Whether he was truly a locker-room problem was a moot point. Whether he was actually unwilling to punt and stay quiet didn’t matter. Despite tryouts with the Texans and Cowboys, King never received another NFL opportunity.

“I feel the role of social media played a negative role in his ability to explore other opportunities in the NFL,” Silberman said. “He was misunderstood often.”

“The people that work for the NFL that want the entertainment and want to bring the camera people out to shoot and stuff, versus the coaches and how they want s— to run — they butt heads a lot,” King said. “The people that do content for the NFL loved all the s— that I was doing. Some of the coaches didn’t like it.”

Neither did some of his peers. King said he was approached by other punters about his nonconformity. The gist of their message: “Why can’t you just do like we do and just kick the ball, do your job and get off the field?”

King’s response?

“I didn’t grow up like y’all,” he said. “I went to an HBCU and, I mean, s—, I just got style, man. I got seasoning. The way I grew up, I just wasn’t taught the same way. Most of the kickers and punters in the league are, what, 95 percent White?”

King tried to pick himself up. On good days, he sipped wine and watched the sunset. On bad days, he’d lie around the house “depressed as f—,” replaying all his missteps.

“It was so negative to where I couldn’t really pull myself out,” King said. “It was just low, low frequency.”

When discussing punters who broke the mold, the first name that might spring to mind is Pat McAfee, who had the soul of a WWE star and the charisma of a stand-up comedian while owning one of the strongest right legs in the league.

The longtime Colts punter retired after the 2016 season at age 29 to pursue a full-time career in media and is now one of the highest-paid figures in the industry. McAfee has shouted out King numerous times online and, during a charity event, called King “one of my favorite humans walking this earth.” King borrowed McAfee’s punt celebration during a UFL game in 2024 and paid homage in an on-field interview, to which McAfee joyously responded on X.

King says he’s enjoyed McAfee’s vault into superstardom because he “found a way to make punters and kickers cool as f—.”

King has spent several seasons punting for the St. Louis Battlehawks and Arlington Renegades of the XFL and UFL He feels that if he were White, he’d “probably” still be in the NFL and “be tolerated a lot more.” There is historical precedent, Loggins said, for expressions of exuberance being perceived differently based on race.

“It transcends the player and it speaks toward the ask of a Black person in the United States to adhere to a politic of respectability that is not indicative of something that a White athlete or a White person has to adhere to,” Loggins said.

King’s identity was tied to football, and having that taken away was difficult. He humbled himself to play in spring leagues, which came with salaries at a fraction of what he previously earned. “I was struggling,” he said.

He says the time away from the league has helped him realize that football was a job, not his identity. He now creates music and custom jewelry and has a clothing line called “Kicksquad.”

“My identity is being authentically me,” King said. “Being authentic to who I am.”

Punting allowed him to do that. But so does recording music, performing at festivals, creating and designing. Whether he left the NFL on his terms or not, there’s solace to be found in discovering who he is outside of the game.

King, who turned 37 in October, might still flirt with the idea of coming back — he tagged the Buffalo Bills in a post on X in October — but, “I’m not pushing to get into the NFL like I used to because I see what it is,” he said. “I understand what it is.”

On Monday, King attended the Raiders’ home game against the Dallas Cowboys as a special guest alongside former kicker Giorgio Tavecchio. King signed autographs and snapped photos with fans, a moment reminiscent of his playing days, when he was one of the team’s most popular players.

It was also a moment that wouldn’t have been possible in the years immediately following his release. “I still felt a certain type of way,” King said. His presence Monday night was the product of King’s peace with his football fate and his place in history.

“It’s one of those things where you can sit around and feel bitter about it or you can do something about it,” King said. “I had to talk to myself and let myself know, ‘At least I did it.’ I got seven years under my belt. I did it. I still made an imprint in the game, no matter what.”