By Finn Farmer

Chicago is renowned for its numerous contributions to musical history. Chicago is where Delta blues went electric, where queer DJs electrified disco’s corpse with Roland synthesizers to create house music, and where generations of young, independent rock bands have cut their teeth.

Believe it or not, our city has also served as a hugely important incubator for country music, from a brief midcentury stint as the pre-Nashville center of the country-western recording industry to subsequent decades of quiet, hardscrabble innovation in dives across the city. One might expect the musical traditions of rural America to be at odds with the sensibilities of a dense urban jungle, but country music has nonetheless earned an important place in Chicago’s cultural landscape.

Throughout the mid-20th century, a lack of jobs pushed millions of Southerners northward. Chicago’s centralized location and diverse economy brought many of them here, and they’ve left an indelible mark on the city’s musical traditions. African-American transplants quickly turned the city into a widely heralded mecca of blues music, but droves of white Southerners, mostly by way of Appalachia, brought their music with them as well.

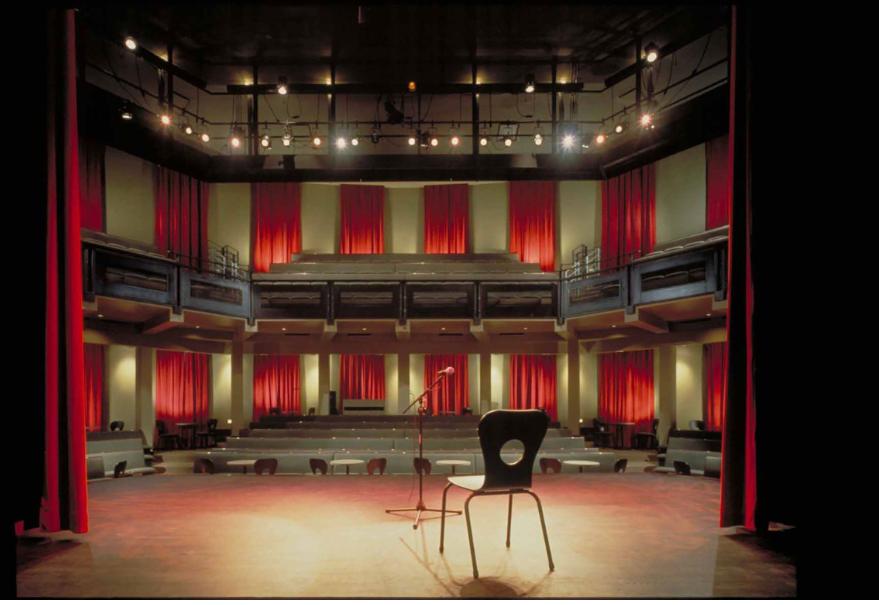

Country music has a significant presence in Chicago dating back at least to the 1920s, when radio smash WLS National Barn Dance began airing. Devised by Edgar L. Bill as a saccharine tribute to the “old-time” country music he’d grown up on, the program was among the earliest nationally syndicated radio broadcasts, predating even the better-remembered Nashville equivalent, the Grand Ol’ Opry. During its original run, the program drew talent and spectators from across the outlying states. Scores of people would have to be turned away from the packed 8th Street Theater in the South Loop every Saturday, and the program minted countless icons of early country music like Gene Autry, Bill Monroe, The Carter Family and Red Foley, many of whom cut significant records in the city through the 1940s.

During the 1950s and 1960s, WLS Barn Dance’s popularity faded, and with it, Chicago’s prominence in the national landscape of country music. Journalist, historian, and author of Country and Midwestern, Mark Guarino, attributes this to broader trends in the recording industry as well as a reluctance to modernize on behalf of Barn Dance’s execs.

“The recording studios really moved as the entertainment industry at the bigger corporate level was still being created in the early part of last century, and so there was a shift,” he said. “Because of the cost of centralizing everything to New York and Southern California, a lot of the recording centers left [Chicago] so there was no reason for people to come here to make records anymore.

“Barn Dance sort of lost its relevance in the time after World War II because the people who were producing it weren’t really interested in keeping up with trends or being in kind of a place for new artists to go to. New or exciting artists, they weren’t going to the Barn Dance. Nashville really was becoming the place where a lot of the newer music was coming out of.”

Barn Dance chugged along as a hokey nostalgia act until it was finally taken off air in 1968, by which time the torch music it helped popularize was being quietly carried along by small, disparate scenes across the city. From the black country musicians and University of Chicago student folk archivists in Hyde Park, to the burgeoning singer-songwriter scene in Near West Side clubs like the Gate of Horn, to the music of the sizeable Appalachian diaspora in Uptown, various strands of country music found homes in dark corners of the city. The latter, Uptown’s Appalachians, left a disproportionately large impact on Chicago’s country music history.

The post-WWII restructuring of America’s economy sent millions packing from places like Virginia, Kentucky, and Tennessee towards cities in search of better jobs. Chicago saw many of these arrivals, most of whom landed in the city’s Uptown neighborhood. Now heavily gentrified, the Uptown of the 1960s and 70s was a much rougher place. Poverty, addiction, and unemployment were rampant amongst the community. Barroom stabbings and arson were commonplace.

Moreover, Appalachians in Chicago were widely stereotyped as violent, uncivilized leeches and faced a great deal of discrimination in hiring and housing.

Despite the hardships these people faced, they continued to celebrate their culture through music. Through subgenres like bluegrass, Appalachia has a rich social music tradition, with many laborers and “normal” people dabbling in instruments and a fondness for impromptu jam sessions. The music of Appalachia has historically been tied into the lives of many of its denizens in a way that’s a lot deeper than you’d find with other genres and groups of people. This tendency continued in Chicago, where amateur and professional musicians alike met nightly in the neighborhood’s many taverns to share songs that reminded them of home and lamented their present environment.

The hardship Chicago’s Appalachians faced encouraged them to double down on their cultural heritage, and the rest of the city eventually caught up and saw the value in what they were doing. Guarino stated that “some people moved up here at the time at first generation or second generation had a lot of pride about their Southern roots, and so I think it created more of a determination to play the music and to share the music with people who are already living up here who weren’t necessarily Southern, even though they had a lot of discrimination against them by the city.”

This pride in the face of adversity was reflected outside of their music as well. Appalachian migrants in Chicago also formed a robust network of community organizations to provide resources and advocacy for Uptown’s residents; the Young Patriots aligned with the Black Panthers to promote community resilience and racial justice, JOIN (Jobs or Income Now) lobbied tirelessly for fair treatment in labor; and a network of countless other groups jockeyed to meet the needs of the community.

These efforts culminated in the 1960s with the push to open a racially integrated, mixed-use, planned community called Hank Williams Village in the area bounded by Montrose, Wilson, Clark, and Broadway. The community, named for the country singer who many recognized as a symbol of Southern pride, would have provided thousands of units of affordable housing, shops, parks, a school, a clinic, and all manner of other social services and amenities, ultimately lost out to Mayor Richard J. Daley’s plans to develop Truman College on the site. This defeat, coupled with other factors, ultimately led to many of Chicago’s Appalachian migrants decamping to the suburbs or returning home, effectively putting an end to Uptown’s years as Chicago’s “Hillbilly Heaven.”

Even so, they’d left their mark. Though the city’s Appalachian diaspora never yielded any widely remembered stars, the musical styles they brought with them influenced the city’s musical DNA significantly, and the social organizations they established serve as a model to activists to this day. Most of the taverns they opened and haunted are now defunct, but Carol’s Pub at Leland and Clark, one of the most notorious, remains a popular venue to this day. Once known as widely for its seedy and violent reputation as the music it hosted, the site was recently renovated and now caters to all manner of musically curious Chicagoans. It’s both a living museum of one of Chicago’s most idiosyncratic subcultures and a curious reflection of the changes Uptown has undergone since its Hillbilly Heaven days.

Since the departure of Uptown’s Appalachians, country music has proliferated in several interesting ways across the city. The Old Town School of Folk Music, founded in 1957, continues to serve as a valuable community resource for the preservation and dissemination of traditional American music. Through the 1990s, a new generation of musicians led by the likes of Wilco reinterpreted country music with modern auteur sensibilities, birthing the “alt-country” movement of which Chicago served as an important center.

Even more recently, as country music has returned to the spotlight of popular music, a rash of country bars have sprung up in Wrigleyville. Ed Warm, the man who purchased Carol’s from its original owners, runs Windy City Smokeout, a barbecue/country music festival that’s grown massively in popularity over the last decade or so. This most recent wave is very “Nashville”, for lack of a better word, lacking the grit and authenticity of the city’s earlier country scenes. The recent proliferation of country trappings across the city seems to be more of a market-oriented response to the broader cultural zeitgeist, but it’s nonetheless exciting to see Chicagoans coming to appreciate the music that’s quietly called the city home for nearly a century.