When you buy through links on our articles, Future and its syndication partners may earn a commission.

Credit: NASA’s Scientific Visualization Studio – Mark SubbaRao, A. J. Christensen, Francis Reddy, Scott Wiessinger, David A. Smith, Elizabeth Hays, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

QUICK FACTS

Milestone: Radio pulsars discovered

Date: Nov. 28, 1967

Where: University of Cambridge, U.K.

Who: Jocelyn Bell Burnell

An astronomy graduate student in England was scouring more than 100 pages of data per day from a radio telescope when she noticed a strange, repeating signal that she dubbed “LGM” — short for “little green men.”

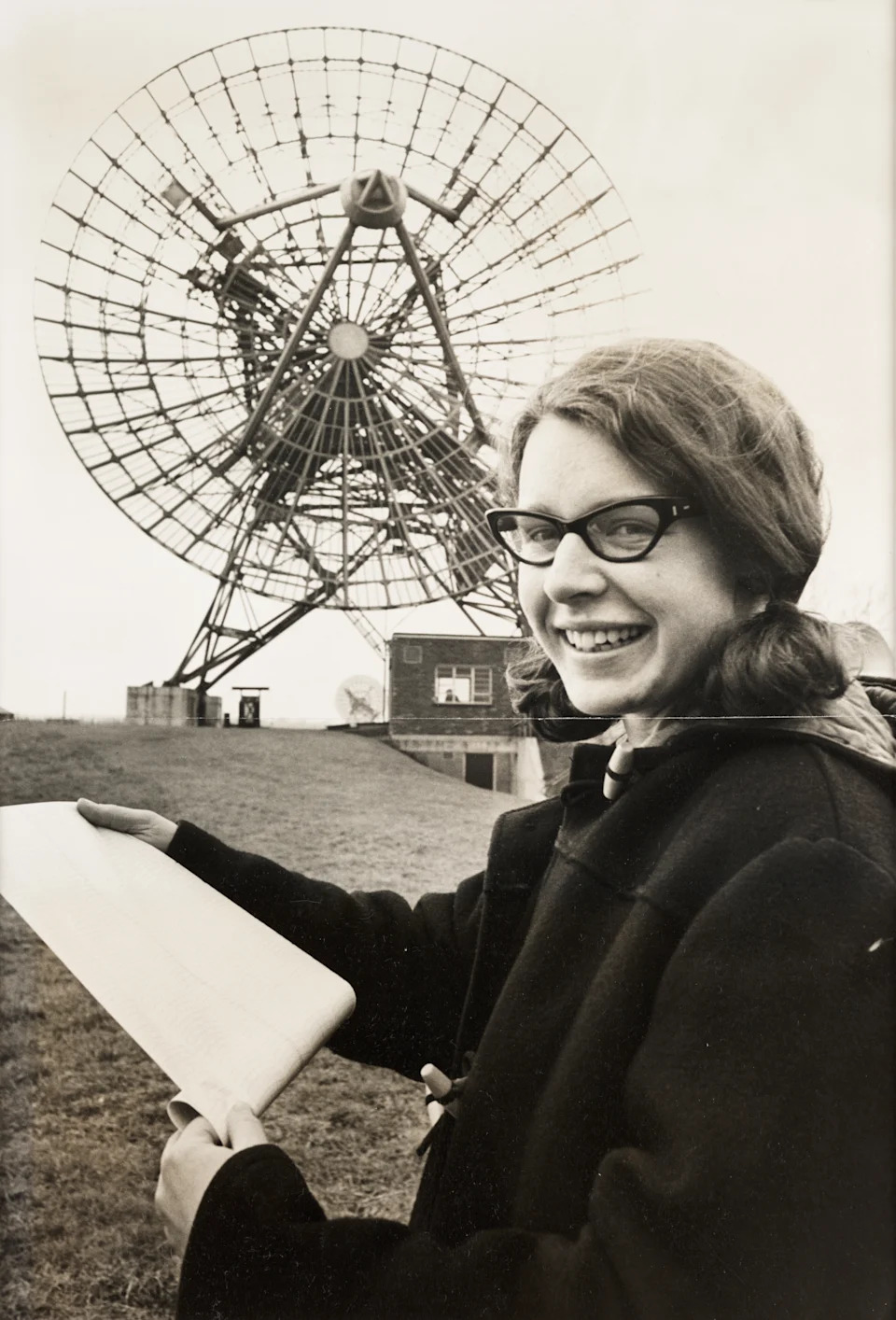

The doctoral student, Jocelyn Bell Burnell (then Jocelyn Bell), had helped build the radio telescope, called the Mullard Radio Astronomy Observatory. The “observatory” was an inelegant mishmash of wires and cables strung from posts, spanning a space about the size of 57 tennis courts, and it looked a bit like a frame you’d use to grow pea plants, Bell Burnell said in a Q&A with the University of Cambridge in 2018.

Bell Burnell was solely responsible for operating the observatory and analyzing the data, and for weeks, the grad student had seen a strange “bit of scruff” in a sea of radio data from the observatory.

“From one particular piece of the sky an unclassifiable signal sometimes recurred and my brain started to say: ‘You’ve seen something like this before, haven’t you? You’ve seen something like this before from this bit of the sky, haven’t you?” she said in the Q&A.

She nicknamed the recurring blip “little green men” because that was what she dubbed an unclassifiable signal that wasn’t tied to an obvious source of interference, like car noise or glitches in the wiring.

She took out earlier recordings and noticed the same signal, which she took to her adviser, Antony Hewish. Hewish noted that the squiggle made up only 1 part in 10 million of the data and suggested she needed a faster recorder.

For a month, she heard nothing. Then, on Nov. 28, she found a string of pulses 1.3 seconds apart. She notified Hewish, but when he came to observe on a separate telescope, nothing showed up.

A photograph of Jocelyn Bell Burnell at the Mullard Radio Astronomy Observatory at Cambridge University, taken for the Daily Herald newspaper in 1968. | Credit: Photo by Daily Herald Archive/National Science & Media Museum/SSPL via Getty Images

“It was a horrible moment,” Bell Burnell said “And suddenly there it was, five minutes later because we had miscalculated when the telescope would see it.”

The duo tried to figure out what it was coming from. It didn’t originate from ordinary sources of interference, and it was too fast to be coming from any known type of star.

Then, Bell Burnell noted another bit of scruff with a regularly repeating signal from a different patch of the sky. All told, over the next month, they found four such signals. Hewish, Bell Burnell and colleagues submitted their discovery to the journal Nature. Soon after, Hewish gave a talk at Cambridge about the discovery, which sparked a media frenzy about the possibility of aliens.

That media attention came with a big dose of silliness and sexism.

“Journalists were asking relevant questions like was I taller than or not quite as tall as Princess Margaret, and how many boyfriends did I have at a time?” Bell Burnell recalled.

Bell Burnell and Hewish quickly ruled out aliens, and by the following year, scientists had found dozens of these strange cosmic repeaters.

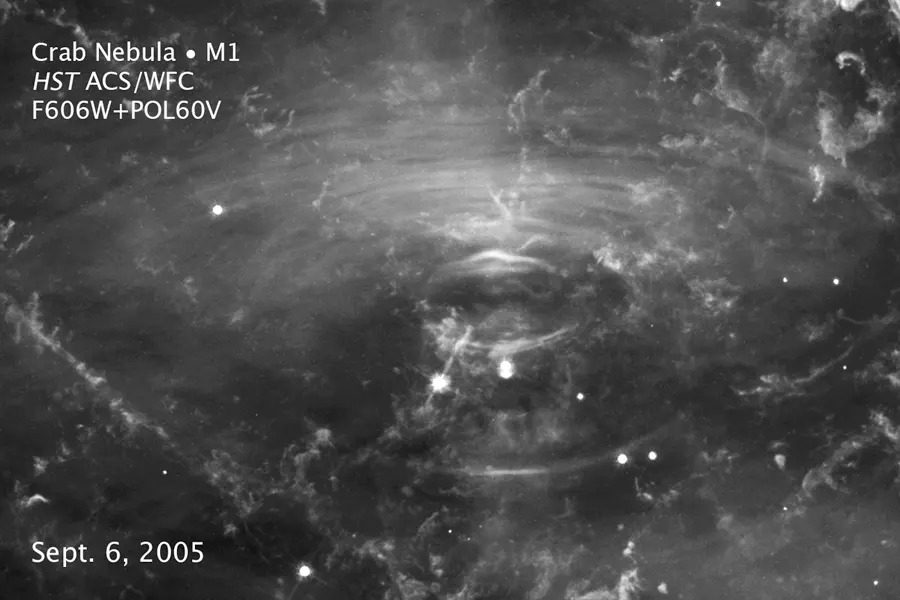

A time-lapse animation of the famous Crab Nebula (M1) created from a series of 10 Hubble exposures. Those wave-like rings are coming from a pulsar at the nebula’s center. | Credit: NASA and ESA; Acknowledgment: J. Hester (Arizona State University)

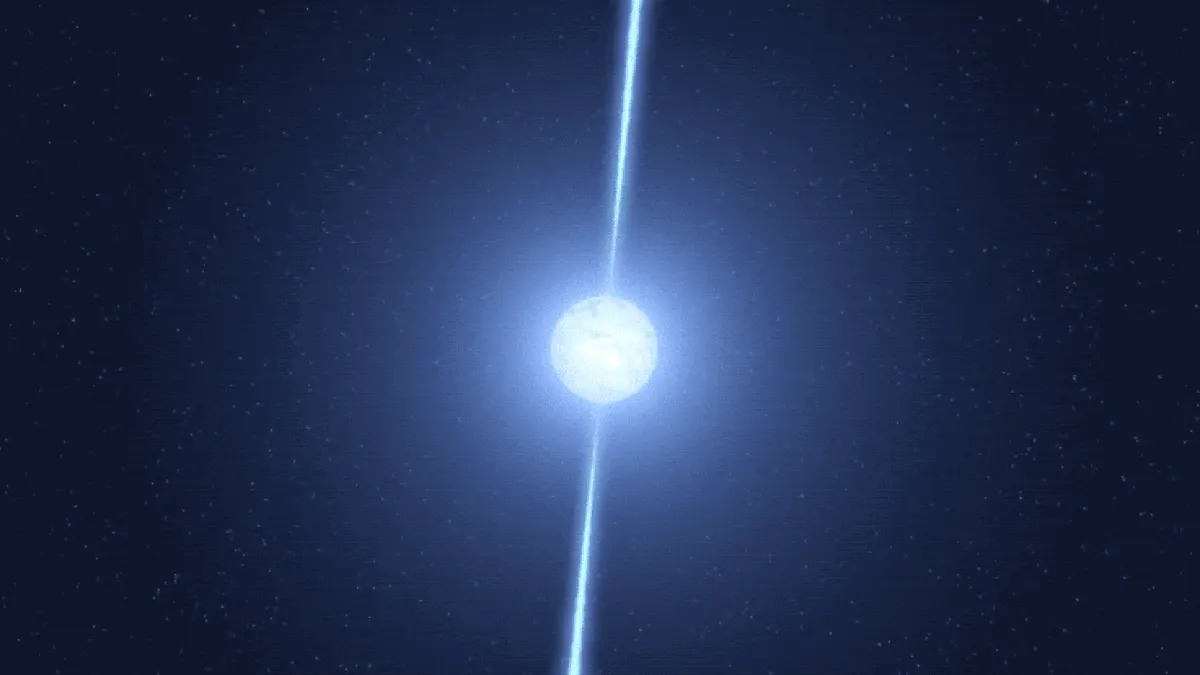

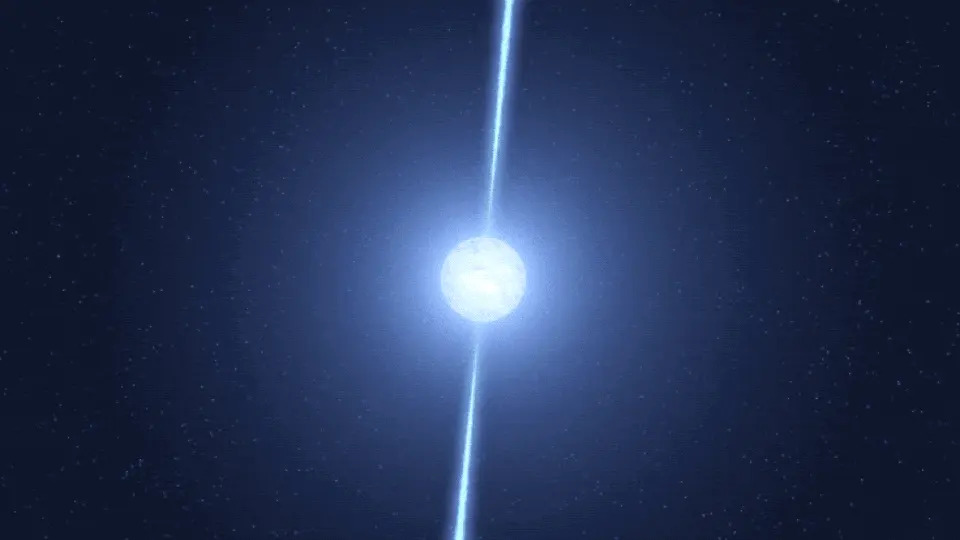

In May 1968, astrophysicist Thomas Gold showed that the mysterious signals came from pulsars — rapidly rotating neutron stars that, like cosmic lighthouses, consistently sweep beams of radio waves across the cosmos. (Neutron stars are ultradense, collapsed cores of stars that have gone supernova.)

Pulsars send out regular beams of radiation because their powerful magnetic fields are misaligned with the remnant star husks’ rotational axes, according to the American Physical Society.

In 1974, Hewish shared the Nobel Prize in physics for his discovery of pulsars with Martin Ryle, one of the key creators of the radio telescope. Bell Burnell was snubbed, prompting some to dub the awards the “No-Bell Prizes.”

MORE SCIENCE HISTORY

—Iconic ‘Lucy’ fossil discovered, transforming our understanding of human evolution

—Experiment shows mutations arise spontaneously, supporting pillar of Darwinian evolution

—‘Patient zero’ catches SARS, the older cousin of COVID

Bell Burnell, for her part, took the snub philosophically. She noted that it was always up for debate whether an adviser or mentee gets credit for research, and thought the Nobel shouldn’t be bestowed on students except in rare cases.

“I am not myself upset about it — after all, I am in good company, am I not?” she joked about not receiving the award.

Bell Burnell later left radio astronomy to work in X-ray and gamma-ray astronomy. But her legacy was eventually honored. In 2018, she was awarded the $3 million Breakthrough Prize for her part in the discovery of pulsars. She donated her prize winnings to fund a scholarship.