About 4.5 million years ago, a great cosmic dog kicked past our Solar System – and its effects may still be seen today.

Astrophysicists calculated that two stars, now located some 400 to 500 light-years from Earth, swung through our neighborhood on their journey through the Milky Way, coming as close as 32 light-years. These stars now make up part of the legs of the constellation Canis Major, the “greater dog.”

“These two stars would have been anywhere from four to six times brighter than Sirius is today, far and away the brightest stars in the sky,” says Michael Shull, astrophysicist at the University of Colorado (CU) Boulder.

While they’ve since dimmed as they’ve retreated into the distance, these stars could have left their mark in other ways. Their intense heat may have ionized gas in local interstellar clouds that shroud our Solar System, to a degree that had previously puzzled scientists.

Related: Earth Possibly Exposed to Interstellar Anomaly Millions of Years Ago

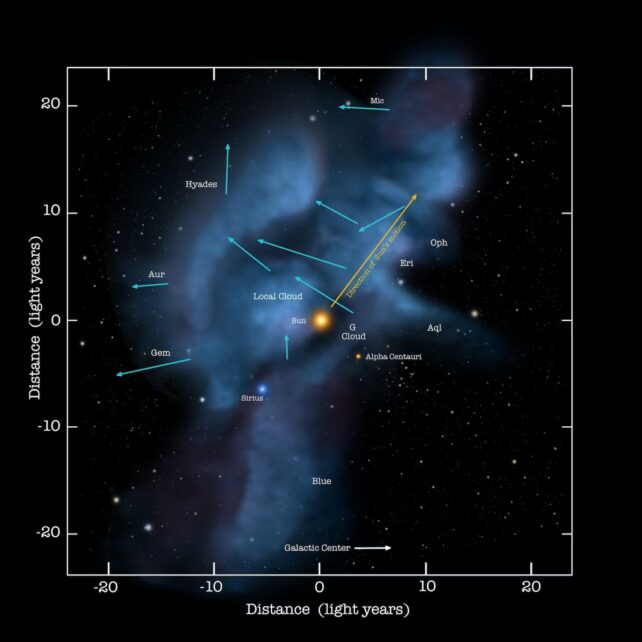

Our little Sun, along with the planets that follow it, occupies a kind of galactic nesting doll within a giant void known as the Local Bubble, where interstellar material is far less dense than the Milky Way’s average.

But inside that bubble lies a pocket of relatively dense matter that astronomers call the local interstellar clouds – and within that sits the Solar System.

Roughly 30 light-years in length, the local clouds are composed mostly of a form of hydrogen and helium that exhibits a surprising level of ionization. According to previous studies, around 20 percent of the hydrogen atoms and as much as 40 percent of the helium atoms are charged.

To achieve that requires powerful sources of radiation, which knock electrons out of the atoms in the clouds. But known sources in the area – such as supernovae that ‘blew’ the Local Bubble in the first place – don’t quite account for the whole picture.

A diagram of the local interstellar cloud. (NASA/Adler/U. Chicago/Wesleyan)

A diagram of the local interstellar cloud. (NASA/Adler/U. Chicago/Wesleyan)

This mystery is what initially inspired the new study. The researchers simulated our local region of space over the past few million years to see what radiation sources may have contributed to the strange ionization in the clouds.

“It’s kind of a jigsaw puzzle where all the different pieces are moving,” says Shull. “The Sun is moving. Stars are racing away from us. The clouds are drifting away.”

The team identified at least six sources of radiation at work. One is the hot plasma along the edge of the Local Bubble, which fires off a significant amount of ionizing photons. Three nearby hot white dwarfs are also doing their part.

The final two pieces of the puzzle, the team suggests, are Epsilon Canis Majoris and Beta Canis Majoris – two of the stars that make up the constellation of Canis Major. Although they’re hundreds of light-years from Earth now, about 4.4 million years ago, they passed within 32 light-years of our Solar System.

These are B-type stars, meaning they’re much bigger and hotter than the Sun. That extra energy would have left a trail of hot ionized gas in their wake, as they slowly drifted away to their current locations.

That ionization won’t last forever, though: Random electrons floating around in space will return the atoms to neutral charges over time.

Earth itself might be in for a higher dose of radiation in the future. At the moment, our location inside these clouds protects us from the worst of the interstellar medium, but it’s expected that the Solar System will drift out of the clouds in less than 2,000 years’ time.

The research was published in The Astrophysical Journal.