BOSTON — The offices at John Quackenbush’s lab at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health were once full of postdoctoral fellows, graduate students, and interns. Young scientists here worked on some of the most cutting-edge computational biology research in the world, driving new discoveries and the creation of widely used big data tools, including one the National Cancer Institute named among the most important advances of 2024.

Today, the offices are rows of empty computer pods. Monitor brackets at each station hang in the air as bare as bleached corals.

The disaster that struck Quackenbush and his lab began earlier this year, when the Trump administration began rapidly slashing funds that fueled research programs all over the country.

His is one of hundreds of labs that have been struggling to stay afloat since. Universities, facing the threat of even more deep cuts to National Institutes of Health funding in the near future, laid off support staff, reduced hiring, and recruited fewer graduate students and fellows.

For years, Quackenbush’s lab has been at the forefront of human genetics research and bioinformatics. The computational tools developed by the lab help scientists understand how genes are controlled and how things go awry in diseases from cancer to autism, and make it possible for scientists to model cell biology and genetics at a deeper, more complex level. That’s why many of the “most influential labs in the world” tend to collaborate with Quackenbush, said Kenneth Ramos, a cancer researcher at Texas A&M Health. As of this year, Quackenbush’s work has a staggering 100,000 citations.

“John has been one of the most impactful bioinformaticians working in the genomic space in the last 25 years,” Ramos said. “He made a lot of resources he developed publicly available. He is bright, curious, and digs deep into scientific questions. And he is kind, the most collegial person you can imagine.”

Quackenbush anticipated trouble, to an extent. When Donald Trump won the presidential election in 2024, Quackenbush decided to stop hiring new trainees. “I read the Project 2025 stuff. I knew biomedical research was in the crosshairs,” he said in an interview with STAT. If something happened to scientific funding, he wanted to make sure he could stretch whatever dollars he had for as long as possible. “I held back, trying to be cautious, not knowing what would happen,” he said. “And the money is now basically gone.”

A major loss came in April, when Quackenbush, like many other scientists over the past year, learned that a research program he depended on was gone. He had submitted a renewal application for a grant to study sex and gender differences in medicine, but communication freezes and other disruptions delayed the review date. Then, on April 4, the review date for the grant vanished, and a program officer told Quackenbush that the program had been terminated because it “no longer aligned with administration priorities,” a phrase that was quickly becoming familiar to scientists working on similar research.

Then the National Cancer Institute (NCI) ended its Outstanding Investigator Award program, a critical source of funding for Quackenbush that covered some of his salary. The program provided seven years of funding and was meant to minimize paperwork and incentivize the best researchers to pursue high-risk, high-reward science, both things that NIH Director Jay Bhattacharya has said are priorities for him. While those with ongoing awards will still continue to receive funds, Quackenbush’s reached the end of its seven years in 2025. He had expected to renew the grant, he said, based on the renewal application’s review scores, until the program ended. Then, the administration denied a no cost extension, which would have allowed him to spend down remaining dollars in the grant.

“That was devastating. And then, I was on a plane over Lake Michigan and all the mass terminations for Harvard grants came through,” Quackenbush said. “It was the same thing. I had this visceral feeling of fear and anxiety.”

With the loss of so much research funding, not hiring is no longer a choice, but a necessity. As students graduate and postdocs leave for other jobs, Quackenbush doesn’t have the dollars to bring on replacements. The research program he has spent decades building at Harvard, that has proven useful to countless other scientists, is in danger of collapse.

A whiteboard celebrates Quackenbush’s lab, whose tools enable research on cancer, autism, and more.Sophie Park for STAT

A whiteboard celebrates Quackenbush’s lab, whose tools enable research on cancer, autism, and more.Sophie Park for STAT

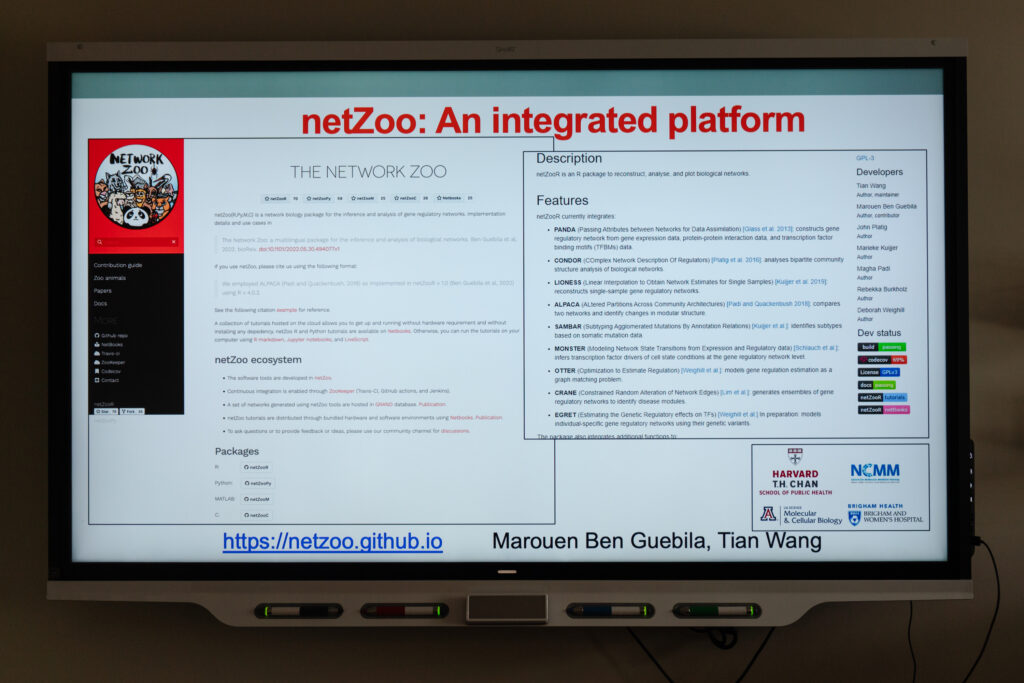

Most scientists familiar with Quackenbush’s work know him as a methodologist, a computational tool builder. Over the last two decades, his lab created a suite of applications called the “Network Zoo,” machine learning tools focused around understanding gene regulatory networks, the web of molecular interactions and systems that control how cells use their genes.

To explain, Quackenbush points out that every cell in a human body has the same genome. The thing that separates a neuron from a liver cell are the different arrays of genes that are silenced or active in one versus the other. “But that is what is different, not why they are different,” Quackenbush said.

Working with monkeys was this lab tech’s dream job. Now she’s staffing an IT help desk

Quackenbush became interested not just in which genes are active or silenced in cells, but in these complex networks consisting of 1,600 transcription factors, proteins that regulate the over 20,000 genes in the genome. “These transcription factors work alone and together to orchestrate when and how strongly genes turn off and on, activating not just one gene or another, but collections of genes that work together to carry out unique processes,” he said. “It’s a many to many problem. So you have this complex network that potentially has hundreds of thousands of connections.”

Modeling and studying these networks can help scientists build a deeper understanding of human biology and potential disease causes and therapeutics. But the only way to model such a network is through computational tools like the ones that Quackenbush and his lab build, said Ramos at Texas A&M. Each application in the Network Zoo is named after a different animal, like PANDA or EGRET, and can help scientists explore different aspects of gene regulatory networks. One recent application, PHOENIX, helps scientists better understand how gene networks change over time and is the first such network model that can scale to all estimated 20,000 genes in the human genome, and was noted by the NCI as a key advance in 2024.

Quackenbush doesn’t see himself primarily as a tool builder, though. To him, the applications are a means to an end, a way to satisfy scientific and biological questions that fascinate him and his colleagues. What truly excites him is being able to use the tools to do science. For instance, he and one of his current postdocs, Tara Eicher, wanted to study how certain genes implicated in glioblastoma, an aggressive type of brain cancer, are related to one another and whether they might help explain certain differences in outcomes between men and women. “Tara grabbed onto this idea and developed a method she calls BLOBFISH, which is the ugliest or cutest looking fish in our animal name paradigm,” Quackenbush said. “It’s a creative way to take networks and find how genes are connected within them.”

Eicher and Quackenbush are now starting to use that method to study glioblastoma, and employing BLOBFISH to study genes related to autism as well.

All the Network Zoo tools are open source and freely available for scientists to use, and they’re also relatively easy to use, Ramos said. “What [Quackenbush] did was make bioinformatics accessible,” he said. “He’s written them in code that somebody with reasonable bioinformatics expertise can adopt pretty readily. He’s done that by design.”

In his own work, Ramos used a Network Zoo program called ALPACA to better understand how to overcome drug resistance in cancer. Other researchers, like Brigham and Women’s Hospital physician scientist Dawn DeMeo, have used the Network Zoo to make discoveries in other diseases. A key interest for DeMeo and her lab is sex differences in lung diseases like COPD, asthma, and lung cancer. Before she learned about the Network Zoo applications, DeMeo said it felt impossible to study some of the questions she works on now.

“As a clinician, I knew there were remarkable differences in lung disease between men and women. As someone doing research in genetics and genomics, I felt we didn’t have the tools yet to answer these questions,” DeMeo said.

Collaborating with Quackenbush’s lab made it possible for DeMeo to start finding some of these differences. For one, while actual gene expression, or creation of proteins, is roughly the same in men and women, DeMeo and Quackenbush discovered large differences in how those same genes were regulated between sexes. “We were shocked to find that across many organ systems, we saw this same pattern,” she said. That meant gene regulatory networks might be a key avenue to understand why women respond better to chemotherapy, for example, or why asthma is more common in young boys before puberty but more common in women after puberty.

A slide highlights computational tools developed by Quackenbush’s lab.Sophie Park for STAT

A slide highlights computational tools developed by Quackenbush’s lab.Sophie Park for STAT

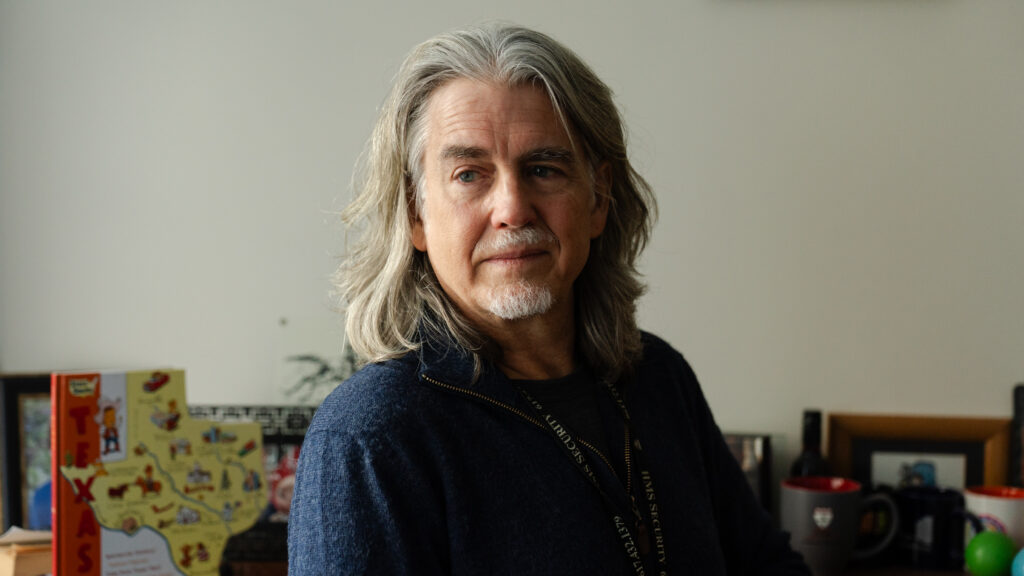

Quackenbush in the room where his shrinking lab meets.Sophie Park for STAT

Quackenbush in the room where his shrinking lab meets.Sophie Park for STAT

The shrinking lab

With the grants that supported Quackenbush’s lab either cancelled or running out soon, the availability of these tools may become more limited. For one, without being able to hire graduate students and fellows, there just won’t be the people power to continue developing new tools to investigate new kinds of questions at the same rate. Quackenbush’s lab also has to maintain the tools, making sure that they remain up to date and compatible with the latest versions of programming languages like Python.

Over time, without lab members to keep this up, the Network Zoo will decay, and scientists like DeMeo and Ramos may not be able to continue using them. “Every time there’s a new release of R and Python, we have to go in and upgrade all the code. Otherwise it won’t run,” Quackenbush said. The lab also supports some of the cost of keeping these resources online. “Now, with more than 20 software tools in this repertoire, it takes a lot to maintain them,” he said.

A year ago, nine postdocs and graduate students made up the Quackenbush lab. Now, he’s down to three. Where lab meetings used to fill up a large conference room, they now meet in a smaller office. As he watched the lab shrink over the year, he said one small mercy was that he hasn’t had to fire anyone. “All these people who worked with me have gone on to good positions,” he said. “Even one of the postdocs working with me now just interviewed for a job. People have gone on to great things, and I’m proud of them.”

Still, the morale among the remaining researchers has fallen. A dark cloud began to hang over the departures. One postdoc told STAT the decision to leave the lab was accelerated by the federal funding cuts and instability in academic science this year. Eicher interviewed for an industry job this year, but withdrew her application.

Still, she’s worried about funding for her postdoc running out. Eicher has two young children, and her family needs both her and her husband’s income to support them. That also makes it more difficult to find jobs abroad, she said, even as leaving the U.S. to pursue science has become increasingly attractive since the start of the Trump administration.

“There are a lot of people talking about going to Europe, given the current climate,” Eicher said. “That’s not really an option for me. I don’t think moving my kids to another country is really feasible at this point. It’s a lot to consider.”

Staying at Harvard feels like walking on thin ice, though. Harvard’s School of Public Health, which has relied heavily on grant funding, has steadily increased austerity measures, cutting costs wherever it could. In the department of biostatistics, there are only four new Ph.D. students, compared to the usual dozen or more. And there’s no more coffee provided, a longtime staple of the break room. “It does give a different feeling,” Eicher said, looking at the empty space where the coffee once sat. “It really illustrates that we don’t have money for any type of thing that we don’t absolutely need.”

Because of his funding losses, Quackenbush has considered moving to another university. He’s also looking for ways to spin out technology startups from his work. “It’s taught me that I am wired in a way that reflects stoic philosophy,” he said. “I look and say, ‘all right, is there something else I can do that will move things forward?’”Sophie Park for STAT

Because of his funding losses, Quackenbush has considered moving to another university. He’s also looking for ways to spin out technology startups from his work. “It’s taught me that I am wired in a way that reflects stoic philosophy,” he said. “I look and say, ‘all right, is there something else I can do that will move things forward?’”Sophie Park for STAT

‘Luckiest person in the world’

For now, Quackenbush still has a small amount of money from grants that continue to support his remaining lab members and cloud supercomputing costs, but it won’t last forever. He estimates the lab has had about $1.2 million lost or withheld this year, and possibly close to $10 million research dollars lost over multiple, future years. What remains is a small subcontract that expires in May, a grant from Amazon Web Services, and “a small amount of money from the NCI that fell in the gap between my grant programs being terminated and the mass terminations, and subsequent restoration, of funding at Harvard,” he said.

He’s been considering other positions as other institutions have tried to recruit him, including the University of Oxford. So far, though, he hasn’t made any decisions — adding that the financial package didn’t make moving the lab over to England feasible.

Quackenbush said he’s been managing the lab’s dwindling finances by looking for new opportunities, like finding ways to spin out technology startups from his work. “It’s taught me that I am wired in a way that reflects stoic philosophy,” he said. “I look and say, ‘all right, is there something else I can do that will move things forward?’”

Even stoics can struggle, though. At an annual physical earlier this year, Quackenbush recalled checking through several mental health questions. “Are you depressed? Yes. Are you anxious? Yes. Hopeless? Yes. It’s just such a challenging time right now,” he said.

What’s been frustrating for him is the sense that many in the public and in the administration don’t understand what scientists like him are trying to do and who they are. “The perceptions are all over the place. We’re at Harvard. We’re the elites. In abstract, it’s easy to make scientists a political scapegoat. But if you talk to people and lay out what you do and ask, are you interested in people trying to cure cancer, the answer is yes,” Quackenbush said. “If you ask them about the things we do on a day-to-day basis, the answer is always yes, it’s important.”

Quackenbush grew up with a single parent in a small Pennsylvania town called Mountain Top. “Wilkes-Barre area, not really quite a town,” he said. “I was supposed to be nothing.” As a high school student, Quackenbush worked as a dishwasher in a restaurant. “One day, the police burst in and arrested our cook and hauled him out. Then my boss said, does anyone know how to cook? I said I can boil water, and he said, you’re promoted,” Quackenbush said.

Later, choosing between going to college and becoming the restaurant’s assistant manager was a big decision. “For me, this was far more than I thought I could achieve — an assistant manager in a restaurant,” he said. But he felt called to Caltech, and so became the first person in his family to graduate college. From there, Quackenbush earned a Ph.D. in physics and did research in theoretical and experimental physics before switching to genetics and starting his lab in computational biology.

The U.S. government and public investment into science supported that journey, something that Quackenbush said he’s grateful for every day. “As a scientist, I feel like I’m the luckiest person in the world. I’ve been able to do really interesting things, and I’ve been paid to do that by the American taxpayers,” he said. “Society has made this investment in me, and my responsibility is to provide a return on that investment.”

That’s harder than ever now, with the lab a shadow of what it once was. Getting new large grants may not necessarily be a quick fix, as private foundation dollars are more in demand than ever, and public grant applications are an intensive and competitive process that may take a year or more. Much of the money he still has will run out in the spring, he said. “I have no idea what’s going to happen beyond that.”

For now, he said, the lab will continue working. “Every day we come in to fight through the current situation as much as possible. We want to continue research. We want to continue to make advances,” he said.

And they will, even if at a much slower pace, Quackenbush said, until they can’t.