He designed some of the world’s greatest buildings — and, in the process, he built an everlasting legacy.

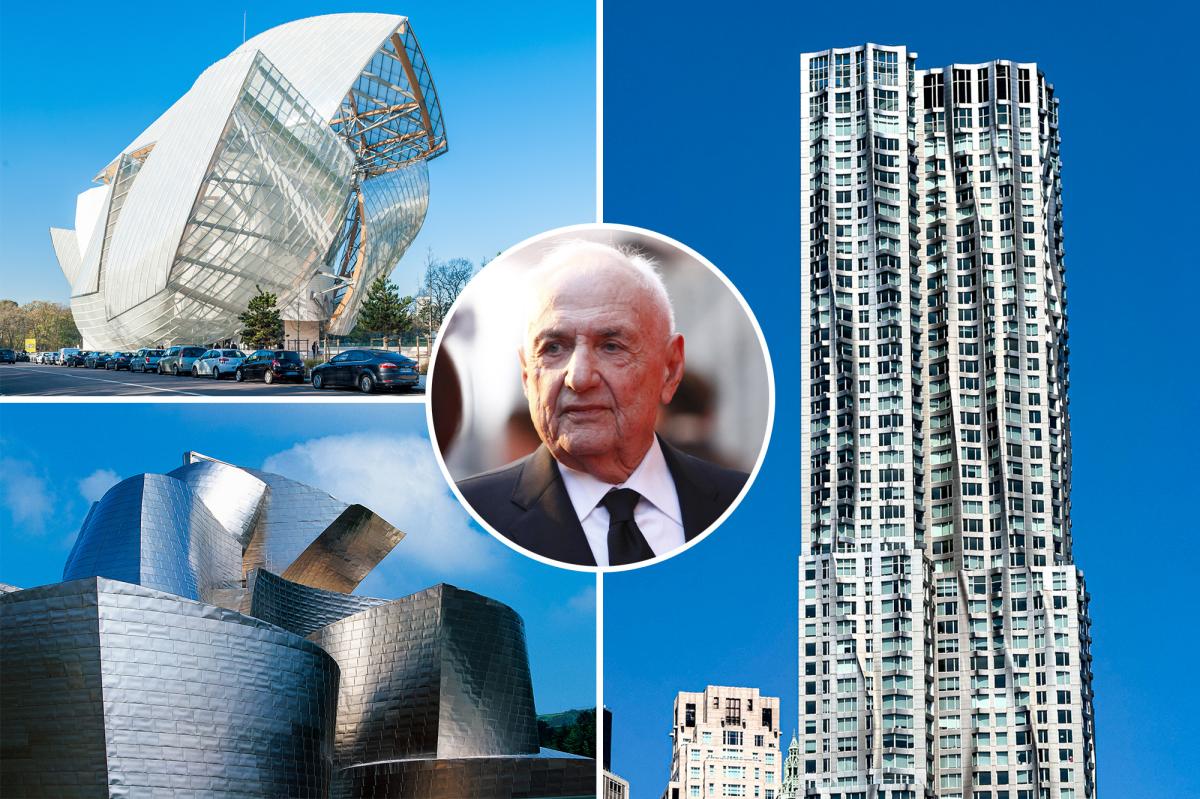

The Pritzker Prize-winning architect Frank Gehry, the mastermind behind the towering 8 Spruce St. in Manhattan and the Guggenheim in Spain’s Basque Country, has died at the age of 96, according to reports published Friday.

He passed away at his home in Santa Monica, California, according to the New York Times, which added his death came following a brief respiratory illness.

Gehry’s most monumental work in New York City stands at 8 Spruce St., located at the Manhattan anchorage of the Brooklyn Bridge. UCG/Universal Images Group via Getty Images

Also in New York, the IAC headquarters in Chelsea, which catches eyes with its curvy white aesthetic. UCG/Universal Images Group via Getty Images

A Gehry building, no matter its location, is an eye-catching landmark — one often defined by wavy metallic details, atypical forms and an immediate lesson in how architecture can be an artful expression far beyond the confines of quotidian function.

In New York, Gehry designed two buildings, both of which stand in Manhattan.

At the end of the Brooklyn Bridge stands 8 Spruce St., an 870-foot luxury rental edifice, which was completed in 2011. At the time of its debut, it was the tallest residential tower in the Western Hemisphere, with a striking look — gentle waves of 10,500 steel panels that change color under differing light and weather conditions — that the Financial District had never before seen.

Housing nearly 900 apartments, 13 units there are presently available for rent — with prices from $4,638 for a studio to nearly $16,700 for a three-bedroom near the top of the building, according to StreetEasy. The 76-story address, the Times noted, was conceived as an architectural triptych with two other nearby pre-war buildings: the Woolworth Building and the Municipal Building.

Gehry died following a brief respiratory illness. REUTERS

His work extended globally, such as at the Fondation Louis Vuitton in Paris. Corbis via Getty Images

“I’m getting tearful,” Gehry told the Guardian the year the building opened, on leaving his mark on the city’s skyline. “My father grew up in Hell’s Kitchen, 10th Avenue, on the city’s West Side … He had a hard life. I’d like to share 8 Spruce St. with him. ‘Hey, Pa! I got to build a skyscraper right by the Woolworth Building. That’s me, Dad. Up there!’”

(Gehry’s father, Irving Goldberg, was a heavy drinker — and in the 1940s while arguing on their front lawn in Toronto, where Gehry was born and raised, he had a heart attack from which he never fully recovered. That memory reportedly haunted Gehry — who changed his surname to dodge the sting of antisemitism — for years down the line.)

“I don’t want to do architecture that’s dry and dull,” Gehry told the Guardian. “When you talk to New Yorkers … like my dad, you want to show them something like Bernini or Picasso, not some dumb thing that bores the pants off everyone.”

Gehry won the prestigious Pritzker Prize in 1989. Getty Images

But 8 Spruce St. isn’t meant to erase his other designs in the Big Apple. Chelsea’s IAC Building, familiar to those driving along the West Side Highway, resembles the many sails on a large ship — and marked Gehry’s first full building in New York City. It was finished in 2007. Among his smaller-scale commissions around town, the titanium-clad cafeteria at magazine giant Conde Nast’s former headquarters in Times Square.

Indeed, titanium was a signature element of Gehry’s designs. Perhaps his most famous example of its use is the titanium-clad Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao, Spain, which debuted in 1997 and quickly earned international acclaim. (The late architect Philip Johnson said he burst into tears the first time he laid eyes on it.) Its masterful design remains a work of art in its own right, but it created something greater: “the Bilbao Effect.” The museum’s presence in Bilbao, an overlooked post-industrial city, revived the metro by making it a destination, luring in 1.3 million visitors its first year.

“The museum in Bilbao, Spain really had a dramatic impact on that city,” Pulitzer Prize-winning architectural critic Paul Goldberger — who wrote the definitive biography, “Building Art: The Life and Work of Frank Gehry,” and spent a great deal of time with him — told The Post. “When a single building makes a town a tourist center, then you know we’re seeing architecture do something quite remarkable.”

The mighty presence of the Guggenheim in Bilbao, Spain transformed the dying industrial city into a buzzy destination. De Agostini via Getty Images

The Walt Disney Concert Hall stands near where Gehry grew up in Los Angeles. Bloomberg via Getty Images

The list of Gehry’s other architectural accomplishments is lengthy. His 2003 Walt Disney Concert Hall in downtown Los Angeles stands near City Hall and the Broad museum.

(“I love Walt Disney Hall in LA, which I think is probably the greatest public building in America of the 21st Century, at least,” Goldberger added. “It showed that we can do a great, monumental building that doesn’t look like anything that came before, but functions just as well and is just as exciting and as emotionally powerful.”)

Meanwhile, Gehry’s Fisher Center — a performing arts center at the liberal arts Bard College in New York’s Hudson Valley — is far more tucked away and surrounded by the school’s sprawling landscapes. Not limited to the US, his Fondation Louis Vuitton opened in Paris in 2014.

The Fisher Center at Bard College in the Hudson Valley for decades has stood tucked away — but still glowing — in the school’s greenscapes. Bard College

Gehry was born in February 1929. As a teen, his father’s deteriorating health forced a family move from Canada to Los Angeles — and they lived near where the Disney concert hall stands today.

He’s survived by his second wife, Berta Aguilera, and their two sons. Gehry had two daughters from his first marriage, one of whom predeceased him in 2008. His sister, Doreen Gehry Nelson, also survives him.

Despite the prestige of his work, Gehry also remained down to earth.

“He was driven and ambitious, but had a manner that was incredibly relaxed and easy going,” Goldberger said. “In fact, he was maybe more skillful than anyone I’ve ever known at hiding how driven and ambitious he was, because he had an easy, relaxed manner about him.”

Though he’s gone now, his work remains permanent — as does the ability to inspire future generations.

“His work awakened the broader public to how exciting contemporary architecture could be,” said Goldberger.