He received advanced training at Brown University and was an attending physician at Tufts Medical Center. While there, he witnessed a young patient die of liver cancer that stemmed from a hepatitis B infection, a death that could have been prevented had the man received a common vaccine for the disease as a baby.

That experience moved Chow to urge members of a federal vaccine advisory committee to affirm that all babies should continue to receive a hepatitis B shot shortly after birth. His plea, submitted in a public comment along with scores of others by physicians, medical societies and state health directors, went unheeded: On Friday, members of that panel did the opposite, voting to undo more than three-decades of vaccination policy that demonstrably reduced cases of hepatitis B in the United States.

The recommendation now awaits approval from Jim O’Neill, deputy secretary of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, to become official.

“We will see more cases of chronic hepatitis B,” said Chow, who now practices at Harbor-UCLA Medical Center in Los Angeles, in an interview this week. “Cirrhosis or cancer, we’ll see more of those cases.”

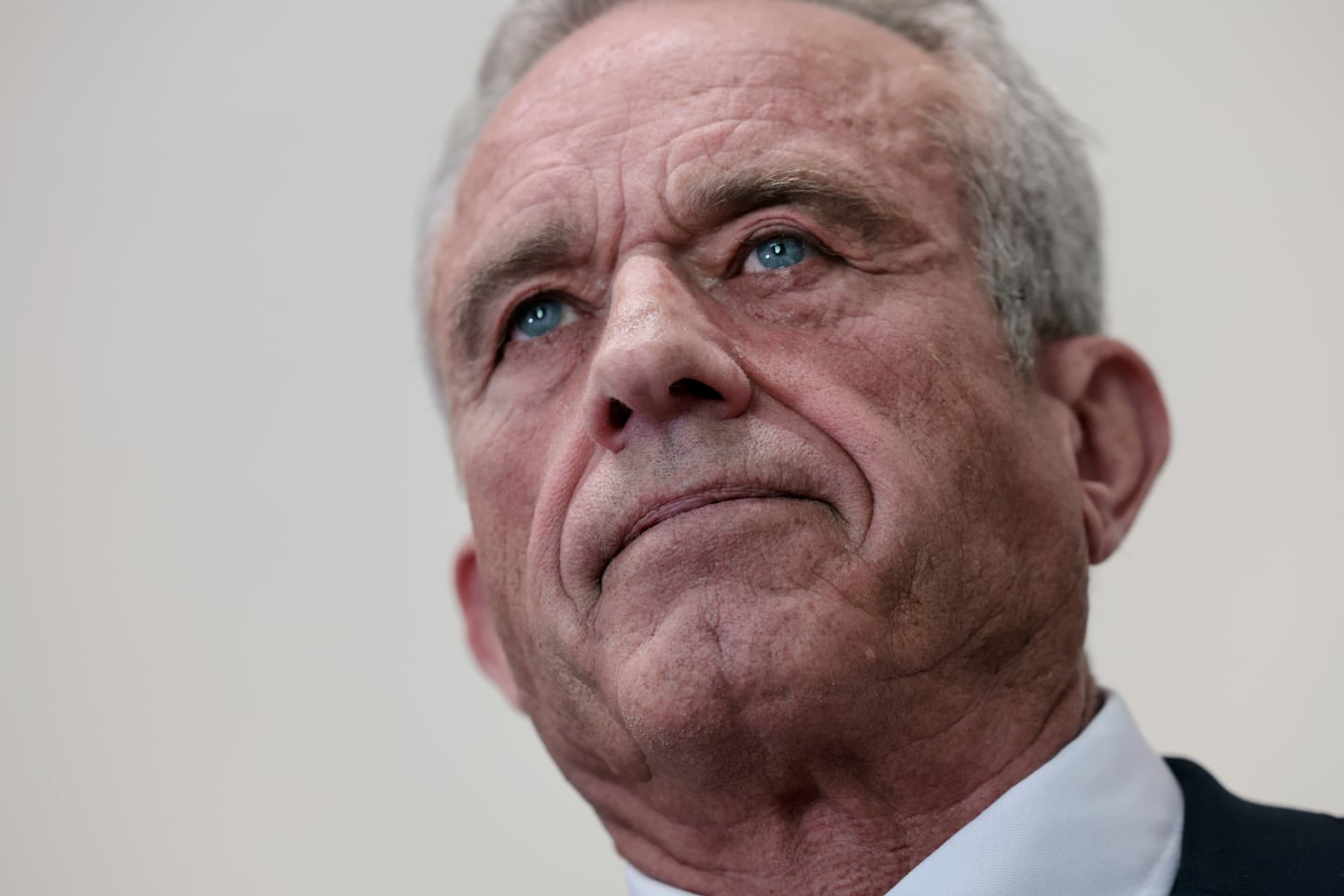

The change to the hepatitis B schedule is the most dramatic step yet in what senior figures in American medicine fear will be a wholesale undoing of not just vaccines, but health policies grounded in evidence-based science, under US Health Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr.

Leading figures in the medical establishment, many of whom are based in New England, see two ways forward:: decades spent regrouping from the changes wrought by the Trump administration, or using this moment of strife to embrace big changes in health care and forge better connections with the people they seek to help.

“There’s a lot of things the community has recognized that are problematic,” said Dr. Craig Spencer, an emergency medicine doctor and public health expert at Brown University, referring to some of the major complaints of the Make America Healthy Again movement.

He described this week’s ACIP meetings as “buffoonery,” but cited the cost of health care, the influence of pharmaceutical companies, and the quality of food as MAHA issues that deserve attention.

“I see a lot of my community almost unwilling to cede any ground,” he said.

The panel, the Advisory Committee for Immunization Practices, is manned by people hand-picked by Kennedy, many of whom embrace discredited theories that vaccines can cause harm in children. Science denialism and alternative medicine have been part of the United States since the country’s beginning, historians said, but this moment is unique.

“They’ve now been able to completely infiltrate existing federal agencies,” said Dr. Peter Hotez, a virologist and vaccine expert at Houston’s Baylor College of Medicine. “That to me is unprecedented.”

Skepticism of established medicine has recently been driven by legitimate concerns over the influence of the pharmaceutical industry in health care, the prominence of ultraprocessed foods in our diets, and frustration with insurance denials. COVID supercharged that discontent. Social distancing orders and masking may have been reasonable precautions, and the COVID vaccine saved lives, but mandates, business closures, and remote schooling fed anger toward public health and medical professionals that the anti-science crowd is still exploiting.

To Kennedy’s supporters, his approach is a needed shakeup to a calcified, insular establishment.

“The American people voted for a change in the status quo,” said Emily Hilliard, a spokesperson for the Department of Health and Human Services. “In less than a year, the Secretary has advanced reforms in public health institutions, strengthened safety monitoring, improved communication with the public, and renewed the focus on informed decision-making.”

That resonates with Elizabeth Frost, a MAHA activist who led Kennedy’s Ohio presidential campaign operation. She isn’t opposed to vaccination, she said, but is deeply skeptical of the medical establishment after seeing the opioid epidemic ravage her Ohio River Valley home. Legal pain killers made by established pharmaceutical companies played a huge role in driving that plague of addiction.

“There was a lot of group think that happens in any industry, any group of people when it hasn’t been shaken up in a while,” said Frost of the national public health agencies.

The members of the panel themselves deny they’re ignoring science. Rather, they are bringing new skepticism to old policies, and considering evidence that contradicts the narratives of established medicine.

“The primary mission of the ACIP committee is to provide independent advice — and I emphasize independent — to the CDC director,” Dr. Robert Malone, the committee’s vice chair, said during Thursday’s meeting.

But other voices in American medicine point out that the people whom Kennedy picked to lead federal health agencies and committees have spread misinformation, cherry picked studies, distorted evidence, and spoke out publicly on topics about which they do not have expertise.

Dr. Rochelle Walensky, a former head of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, said the agency has dramatically changed since she left.

“The voice of the CDC is not of those subject matter experts, and that’s deeply concerning,” she said during a media availability Thursday. Walensky was a Harvard professor and chief of the division of infectious diseases at Massachusetts General Hospital before joining the CDC. She is now back at MGH as a research scholar.

By contrast, the committee’s meetings this week were marked by a lack of discussion and a lack of interest in data that showed the existing hepatitis B vaccination recommendation was effective and safe, she said.

This week’s meeting resulted in the most dramatic change in vaccine policy since Kennedy took office, but it’s not the administration’s first departure from mainstream science. During this year’s measles outbreaks, Kennedy endorsed vaccination, but also suggested Vitamin A is an effective treatment, which is not meaningfully helpful for patients who do not have a vitamin A deficiency, and can in fact cause harm. Also, the federal vaccine advisory panel gave credence to a debunked theory that an additive used in vaccines, thimerosal, was harmful, and added restrictions to chickenpox, measles, mumps, and rubella vaccines that experts called unnecessary.

Much about MAHA echoes other movements in history that opposed mainstream medical science, Hotez said. In the 19th century, Samuel Thomson gained a passionate following selling a system of botanical treatments. The early 20th century’s National League for Medical Freedom opposed government regulation of medical care to make space for “Homeopaths, the Eclectics, the Osteopaths, the Christian Scientists and other schools of Healing,” Hotez wrote.

Opposition to government regulation is common in these movements, Hotez said, as is framing their anti-scientific ideologies as expressions of freedom or independence. Often, the real motive is more base, he said, citing wellness influencers who feed doubt about established science while peddling alternative treatments.

While there’s little precedent for people so far outside mainstream science leading America’s health agencies, there are parallels in other nations. In the 2000s, South African President Thabo Mbeki questioned whether HIV caused AIDS amid an outbreak in that nation. He blocked antiretroviral treatments for the virus, and about 330,000 people died as a result of his policies.

At the time, South Africa had only recently emerged from apartheid, said Benjamin Siegel, a Boston University history professor with expertise in the history of medicine, and the legacy of colonialism was still an open wound on the nation’s psyche.

“It was reasonable people would be distrustful of international authority when it had failed them for so long,” Siegel said.

What comes next is uncertain. Hotez isn’t optimistic. He said the country is just beginning to be inundated by the science deniers, who are amplified by television, podcasts, and social media and empowered by the nation’s health agencies.

“We’ve started the freefall,” he said.

Without action from Congress or the President, he doesn’t anticipate a change of course.

Spencer, the Brown public health expert, doesn’t believe the American medical establishment can go back to the way it was before Kennedy.

“There’s not a world where I see, three years from now, there’s a different administration and we put all these things back in place,” he said.

But, to Spencer, that’s not a bad thing.

In November, he attended a meeting of the Children’s Health Defense, a nonprofit Kennedy founded with a mission to end toxic exposure in children and that has led the anti-vaccine movement. The concerns he heard, that the American health system is expensive and doesn’t get great results for too many people, is compelling, he said. Fixing that, he said, may help deflate anti-vaccine activism.

“I want us to say, ‘we’re willing to engage in how to do things differently,’” Spencer said.

Meanwhile, Frost, the Kennedy campaigner in Ohio, expressed some disillusionment with Trump’s health priorities. She hasn’t seen much action on the issues she cares about, and cuts to funding for local health programs are taking a toll on her community.

“It really woke people up to how much of our daily lives are supported by these programs,” she said.

In his letter to the vaccine advisory panel, Chow, the former Tufts physician, described his terminally ill patient. The man was 30 years old, a scientist and a husband, Chow wrote.

He declined to say where his patient was from, but in his letter to the committee he said, “His only risk factor was being born in a time and place where hepatitis B infections were high [and] use of hepatitis B vaccine was low.”

Chow knew his patient’s story wasn’t likely to change the minds of committee members. But such personal experiences, he believes, can be more persuasive than data alone.

“I still think it’s incredibly important to tell our patients’ stories, to tell the lived experience,” he said. “There will be someone who will read that and will learn the truth, and will make the decision to vaccinate their child or themselves.”

Jason Laughlin can be reached at jason.laughlin@globe.com. Follow him @jasmlaughlin. Sarah Rahal can be reached at sarah.rahal@globe.com. Follow her on X @SarahRahal_ or Instagram @sarah.rahal.