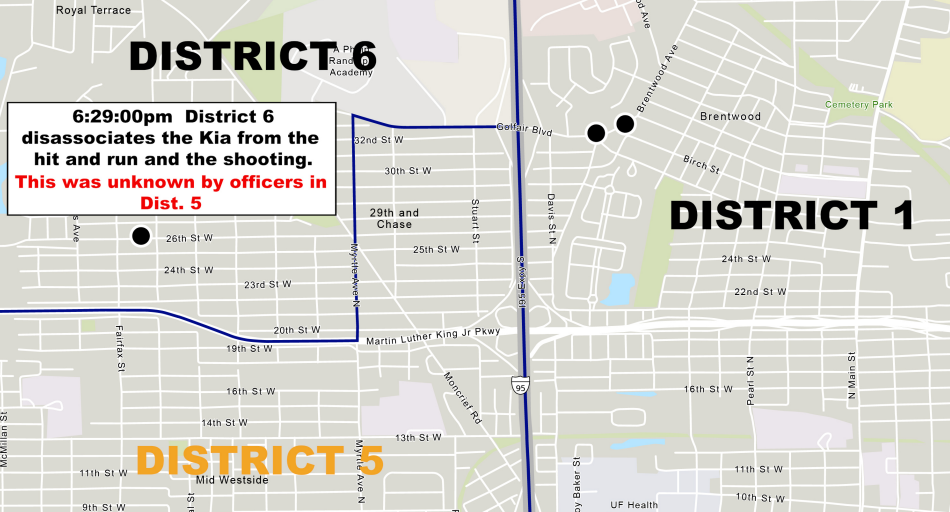

A screenshot of a presentation from State Attorney Melissa Nelson’s office about the circumstances that led to the November police shooting of a 14-year-old boy. Provided.

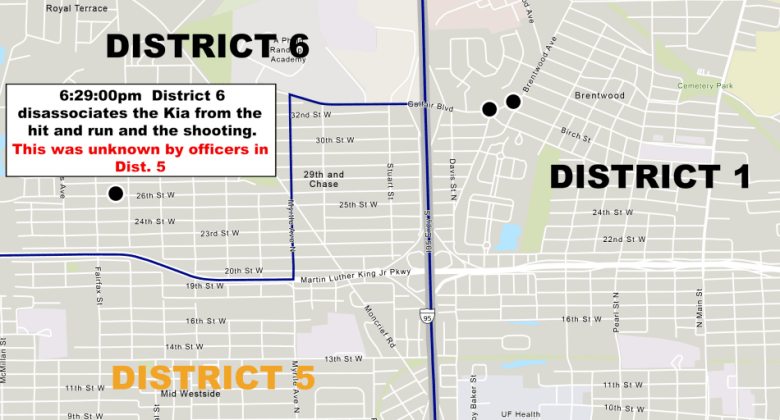

A screenshot of a presentation from State Attorney Melissa Nelson’s office about the circumstances that led to the November police shooting of a 14-year-old boy. Provided.

A communication breakdown within the Jacksonville Sheriff’s Office dispatch system led multiple officers on a frenzied, hour-long search for the wrong car in the wake of a fatal drive-by shooting last month in Northwest Jacksonville. Operating under incorrect information, a JSO officer shot a fleeing, unarmed 14-year-old boy in the back four times, leaving him in critical condition. The boy had nothing to do with the shooting.

State Attorney Melissa Nelson said this week the officer, Jacob Cahill, did not violate any laws by shooting the boy, who survived, because he was working in good faith on outdated information.

A black Kia Optima that the boy and his friends stole that evening from a DoorDash driver for a joy ride was initially suspected of being involved in a nearby shooting, but officers working the shooting scene quickly realized those crimes were not related.

For more than an hour after that revelation, a task force of officers who specialize in catching violent felons continued to roam the districts – and monitored a citywide surveillance system – for the stolen Kia under the pretense that it was the shooting vehicle.

If dispatchers had relayed to the task force that the black Kia was not linked to the drive-by, Nelson said there would not have been a full-fledged pursuit of the four teens, which damaged the Kia and one JSO cruiser, which crashed into a nearby building.

Cahill, however, who was a member of that task force, didn’t know the Kia was no longer the suspect vehicle in the drive-by shooting, so when the 14-year-old boy fled from the scene, he believed he was chasing a potential shooter, Nelson said.

Nelson characterized the circumstances as a “perfect storm” and an “unusual and unfortunate alignment of circumstances,” but the foul-up also revealed a systemic and critical failure in the way JSO dispatchers communicate with officers on the street.

Jacksonville attorney Matt Kachergus, who is representing the family of the 14-year-old boy, who The Tributary is not naming, said in a written statement that the family is disappointed that their child was shot multiple times while Cahill is likely to not be held accountable for the use of deadly force.

“Although the State Attorney has determined there will be no accountability for this officer, the family will seek to hold him accountable in our system of justice,” Kachergus said.

Unclear staffing

It’s unclear how many people work in JSO’s dispatch command center and whether it’s adequately staffed to handle the some 1 million incoming calls each year. Although JSO’s $640 million budget is the largest expense in the city’s general fund, it’s also the hardest to scrutinize because the sheriff has wide latitude to unilaterally shift money and positions around as he sees fit.

JSO budget documents showed in June that there were two vacancies out of 117 JSO police dispatchers. During a news conference this week, Nelson said there were 154 people on staff.

The City Council Auditor’s Office data showed 10 vacant positions out of 120 authorized dispatchers, although Kim Taylor, the council auditor, said those numbers aren’t reliable because Sheriff T.K. Waters can move vacancies at any time.

JSO did not respond to questions from The Tributary about its staffing levels and the discrepancy in the numbers.

JSO has not yet responded to a public-records request related to the same issues.

A flawed system

Still, the November officer-involved shooting demonstrated a dispatch system that operates in silos and which allowed a critical piece of information to slip through the cracks.

“All the dispatchers are right next to each other so they can communicate with each other. When they’re talking amongst each other up there in the comms center, [officers] don’t get to hear that conversation because we’re not present,” retired JSO detective Kim Varner said.

Each of the department’s six districts has its own radio channel for officers to communicate. Typically, officers will only listen to the channel that corresponds to the district they patrol.

There is no citywide channel for officers to communicate updates on the ground, so when crimes cross the boundaries of multiple districts, the system relies on dispatchers in the command center to disseminate necessary information to all officers.

That didn’t happen here.

In a letter to a top JSO official, Nelson recommended that there be a “firm requirement that any time suspect information is updated, corrected, or canceled in connection with any forcible felony, that information be broadcast citywide on all district radio channels without delay.”

Such updates, she wrote, would be a “critical safeguard to prevent similar gaps in the future.”

The State Attorney’s Office has charged all four teens with grand theft auto, a felony. The boy was not taken to jail after his hospital stay.

JSO codified Nelson’s recommendations.

The revised policy says “large-scale and noteworthy incidents that have occurred in a district shall be broadcast citywide over the radio. Police Dispatchers shall never assume the correlation of any calls for service, suspects, vehicles, or persons.”

A shift change at 6:30 p.m., in the midst of officers still hunting for the black Kia, was also cited as a factor in the miscommunication that led to the shooting, Nelson said.

An administrative investigation conducted by JSO of the officer-involved shooting will commence after a Response to Resistance Review Board convenes to assess possible violations of agency policies.

Trinity Webster-Bass is The Tributary’s inaugural Investigative Journalism Fellow.

Related