Early miners panning for gold in California. (Photo via Wikipedia/public domain)

Early miners panning for gold in California. (Photo via Wikipedia/public domain)

Was there gold in them there hills? Yes.

Long before San Diego became known for its beaches, research labs, and urban growth, the mountains to the east briefly thrived with the promise of gold. California’s statewide Gold Rush began in 1848, but San Diego County’s own rush arrived two decades later, sparked by a discovery that reshaped the backcountry almost overnight.

Women and men were known to pan for gold during the CA gold rush. (Photo via Wikipedia/public domain)

Women and men were known to pan for gold during the CA gold rush. (Photo via Wikipedia/public domain)

In late 1869, Fred (A. E.) Coleman, a formerly enslaved cattleman working in the region, found placer gold in a creek near what is now Julian. When Coleman shared his find, prospectors quickly descended on the area, kicking off what is often referred to as the Julian–Banner gold rush. By early 1870, mining camps were forming so quickly that entire settlements appeared, peaked, and declined within months.

Coleman City was one of the first. Founded in early 1870 alongside Coleman Creek, it served miners who panned the shallow deposits and lived in makeshift shacks. Just upstream, Branson City emerged around the same time, complete with a hotel, stores, and a post office that operated briefly in late 1870. These communities existed only as long as the placer gold held out, yet they signaled the speed and optimism of the early rush.

Julian soon became the district’s main hub. It offered supplies, lodging, saloons, and access to dozens of mining claims in the surrounding hills. A few miles east, Banner grew into a busy service town for miners working the canyon’s quartz claims.

At its peak, Banner hosted stores, a blacksmith, boarding houses, and multiple mills. Fires, floods, and a drop in ore quality eventually weakened the town, but several historic structures still stand quietly in the canyon.

Shift to Hard-Rock Mining

By the early 1870s, placer deposits began to decline, and miners turned their attention to quartz veins that required different techniques. Hard-rock mining demanded investment, heavy machinery, and stamp mills capable of crushing ore at scale. These operations brought more structure and capital to an area that had previously relied on simple surface mining.

More mining during the California Gold Rush. (Photo via Wikipedia/public domain)

More mining during the California Gold Rush. (Photo via Wikipedia/public domain)

The most ambitious of these ventures became the Stonewall Mine, located south of Julian in today’s Cuyamaca Rancho State Park. Initially worked in the early 1870s and later redeveloped on a larger scale in the 1880s, the Stonewall operation grew into the county’s most productive mine.

Historical state park reports estimate its yield at well over $1 million in gold, making it by far the region’s largest and most successful mining enterprise.

The mine supported a small settlement known as Cuyamaca City, complete with housing, a boarding house, and work buildings. When mining ceased in 1892, the town rapidly declined, but its footprint remains visible today through preserved foundations, interpretive markers, and equipment fragments maintained by California State Parks.

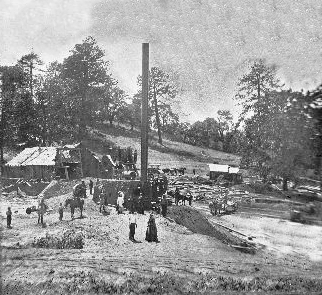

Stonewall Jackson Mine, San Diego County in 1872. (Photo via Wikipedia/public domain)

Stonewall Jackson Mine, San Diego County in 1872. (Photo via Wikipedia/public domain)

Vallecito and the Overland Trail

Although not a gold-mining town, Vallecito played a key logistical role during the era. The Adobe Stage Station — originally part of the Southern Overland Trail — served soldiers, mail carriers, and travelers from the 1850s through the 1870s. Many miners heading toward the Julian area stopped there before pushing into the mountains. The restored Vallecito Stage Station, now a centerpiece of Vallecito County Park, offers one of the most authentic glimpses into San Diego’s broader frontier network.

Vallecito Stage Station. (Photo courtesy of SOHO)

Vallecito Stage Station. (Photo courtesy of SOHO)

Why the Rush Was Short-Lived

San Diego County’s Gold rRsh, though historically significant, was relatively modest compared with other regions. Several factors contributed to its short lifespan: limited deposits — gold-bearing gravels and quartz veins were present but not abundant; water scarcity — seasonal streams made placer mining inconsistent; challenging geology — quartz veins were often low-grade; and transportation difficulties — moving ore and supplies through rugged terrain added cost and risk. By the late 1880s, most major mining operations had slowed dramatically. Small-scale and individual prospecting continued into the early 20th century, but the era of bustling camps, stamp mills, and freshly filed claims had come to an end.

Example of a golf nugget. (Photo via Wikipedia/pubic domain)

Example of a golf nugget. (Photo via Wikipedia/pubic domain)

What Remains Today

Much of San Diego County’s mining story can still be visited. Stonewall Mine offers interpretive signs, foundations, and historic equipment. Julian preserves numerous 1870s-era buildings, museums, and mining exhibits.

Banner Canyon has roadside remnants and historical markers.

Vallecito remains one of Southern California’s best-preserved stage stations. Each site offers a different window into the era — from hopeful prospectors with pans and shovels to the industrial machinery of a full-scale hard-rock mine.

San Diego County’s mining past was brief but influential, shaping early settlement patterns, transportation routes, and the rise of inland communities. The traces that remain today allow visitors to step back into a rugged period when the mountains held the promise of sudden fortune, and the future of the region was still unwritten.

Julian Museum and Pioneer County Park open daily. (Photo courtesy of San Diego Parks and Recreation)

Julian Museum and Pioneer County Park open daily. (Photo courtesy of San Diego Parks and Recreation)

Sources:

San Diego History Center – Mining in the Julian District; Coleman Discoveries

California State Parks – Cuyamaca Rancho State Park: Stonewall Mine Historical Reports

County of San Diego – Vallecito Stage Station County Park History

California Geological Survey – Historical Mining Activities, Southern District

National Park Service – Overland Trail and Southern Emigrant Route Documentation

Julian Pioneer Museum – Historical Exhibits and Local Mining Records

U.S. Bureau of Mines – Historical Mining District Data (Julian-Banner District)

READ NEXT