More than eight years have passed since the deaths of Anita Geuvara’s sister, brother-in-law and four great nieces and nephews, who were trapped in a van trying to escape the floodwaters of Hurricane Harvey.

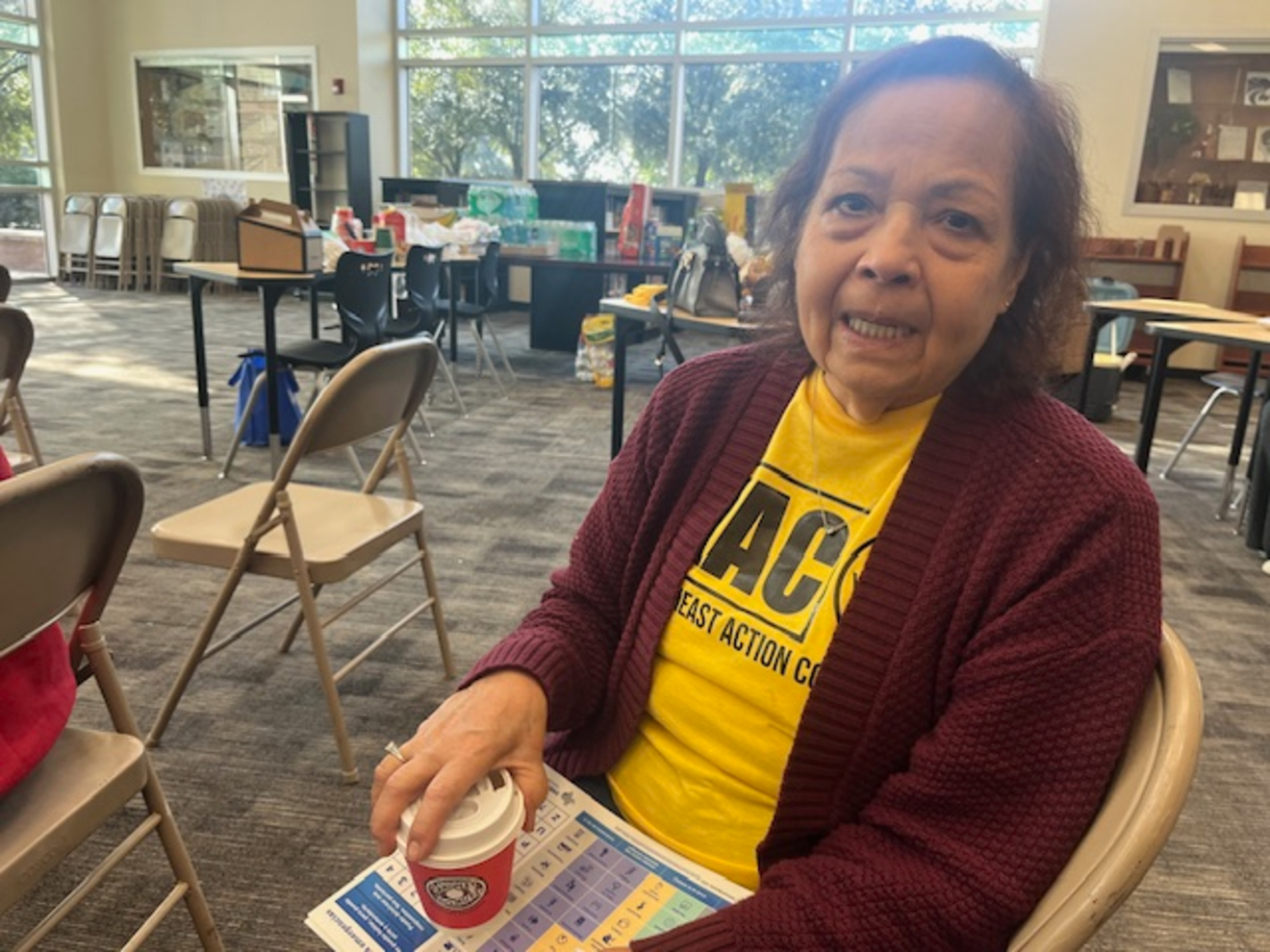

Guevara, 84, didn’t have time to properly grieve the 2017 catastrophe. She was trapped in her home on Kellett Street near Tidwell and Mesa for two days and experienced significant damages and limited, delayed assistance from the Federal Emergency Management Agency.

A few years later in 2021, Guevara and thousands of other Houstonians were again trapped in their homes when they lost power and water for days during Winter Storm Uri.

The longtime resident doesn’t complain about the hand she was dealt. She spent last weekend and the previous one helping seniors and residents of her Lake Forest neighborhood learn how to wrap their pipes, how to administer CPR and what to do when it seems like there’s no assistance in sight.

Guevara and about 50 members of West Street Recovery and its volunteer organization Northeast Action Collective — known for its bright yellow T-shirts and chants of, “When the streets flood, we flood the streets” at City Hall — held a disaster preparedness workshop at Wheatley High School in Fifth Ward on Saturday.

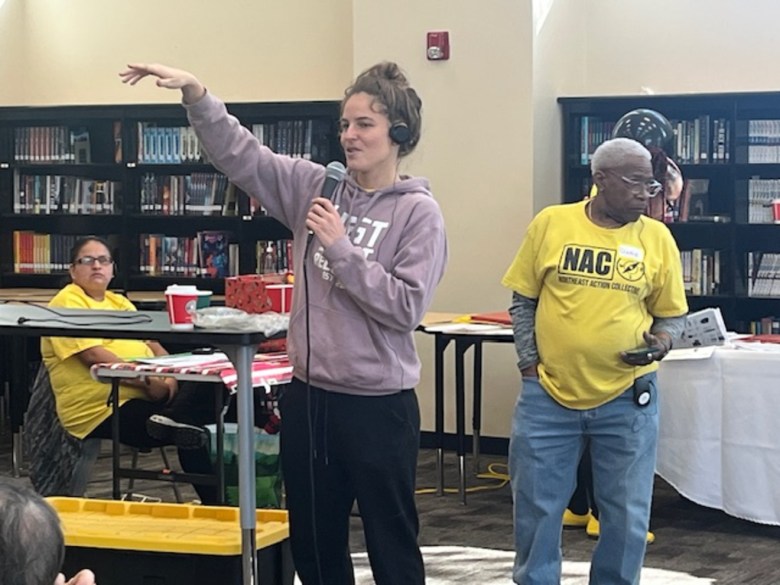

About 50 people showed up Saturday for a disaster preparedness workshop in Fifth Ward. Credit: April Towery

About 50 people showed up Saturday for a disaster preparedness workshop in Fifth Ward. Credit: April Towery

Residents came for coffee and breakfast tacos; they stayed for interactive preparedness drills that NAC volunteer Regina Johnson said could save lives.

Johnson said the organization does more than show up after a storm. NAC recently distributed more than $13,000 to neighbors whose food stamp benefits were paused during the government shutdown. She urged residents at the December 6 event to call upon each other when a crisis arises.

“I want you all to take this time to remember that when there’s a need, and you don’t see any hope, remember the yellow shirts,” she said. “Remember West Street Recovery. Remember we are here to support you and stand with you.”

During Harvey, no one was getting through to 911 or 311 and certainly not City Hall, residents have said. NAC cofounder Doris Brown told the Houston Press in June that when her roof caved in during the 2017 hurricane, it didn’t even cross her mind to call FEMA. She went outside and yelled for her neighbors, checking to make sure they were OK.

Guevara said family members from San Antonio and Corpus Christi made calls for her about her house. She says she was consumed with guilt that she didn’t stay on the phone with her nephew and talk him out of trying to flee. The nephew narrowly escaped the floodwaters in Halls Bayou by cracking a window in the van that held his parents and his four children.

“He said he took his parents out of the home because, at the time, the water was to their waists,” Guevara said. The four children who died in the flood ranged in age from 6 to 16 years old.

“The current was so strong and [my nephew] couldn’t save anybody,” Guevara recalled. “The kids were in the back of the van and my sister and brother-in-law were in the front with him. Luckily, he was small enough to get out. He almost went down himself but he grabbed onto a tree.”

West Street Recovery formed in the aftermath of Harvey, sending inflatable kayaks to pull people out of their homes and helping people rebuild after the deadly storm passed through the Gulf Coast.

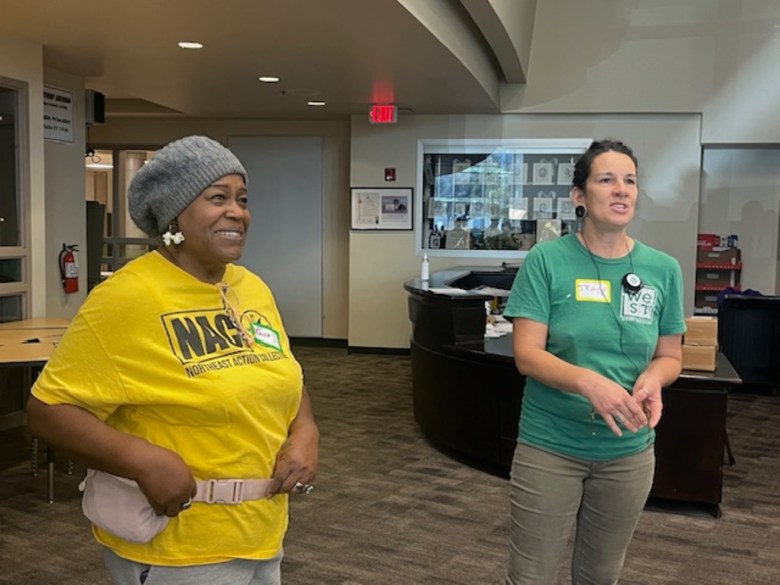

Becky Selle, West Street Recovery’s co-director of disaster preparedness, said the group has been holding workshops twice a year since 2020 to help residents get ready for the next Big One.

“Our winter events are largely centered on our experience from Winter Storm Uri, teaching everything that happened to us and how we’ve adapted since that storm,” she said.

The Texas power grid failed during Uri, leading to more than 246 confirmed deaths and knocking out electricity for 4.5 million homes across the state. The event triggered a long-term water crisis for residents in northeast Houston and “laid bare the failures of our state’s outdated and privatized electricity grid,” Selle said.

Becky Selle, West Street Recovery’s co-director of disaster preparedness, facilitates a training exercise at Wheatley High School on Saturday. Credit: April Towery

Becky Selle, West Street Recovery’s co-director of disaster preparedness, facilitates a training exercise at Wheatley High School on Saturday. Credit: April Towery

Guevara explained that homes in older neighborhoods lack the infrastructure to survive a major storm, and power outages are devastating for her adult son Billy, who is blind and uses a machine to help him breathe. He also recently began dialysis treatments, she said.

Selle said there are hundreds of Houstonians in the northeast part of the city who rely on electronic medical equipment and are vulnerable to the cold.

“During Uri, probably about one-third of homes in northeast Houston lost water,” she said. “The pathway to restore water was delayed and required serious fixes or full re-pipes of the houses. A bunch of sewer lines broke, which shouldn’t happen in the cold but because in some places, the sewage system is so poor and backed up, the sewage pipes actually burst.”

“We were one of the only organizations restoring water access,” she added.

West Street Recovery invested in household-level renewable energy for hundreds of homes and installed cold-resistant piping when making plumbing repairs.

In response to Uri, NAC launched seven “hub houses” where people can go during a power outage to charge their phones or get out of the heat or cold. They can pick up batteries, bug spray, water, fans and other essentials. The hub houses “meet a critical gap in the sparse official government-run shelters and emergency protocols in Houston,” the West Street Recovery website states.

Beth Lumia, another co-director of disaster preparedness, said West Street Recovery and NAC aren’t trying to replace city services but rather develop a social infrastructure so neighbors can support each other.

The Montrose resident got a degree in social work and said she spent her early career supporting disaster survivors and working on recovery efforts, which opened her eyes to the need for preparedness.

Lumia said “of course” there’s a responsibility of local government to help residents prepare for disasters, especially in a city like Houston where unpredictable weather is common.

“They don’t have the tools and the community outreach to be able to do that,” she said. “There has to be collaboration between the public sector and the nonprofit sphere. We have the reach, but they have the money and the authority.”

“Northeast Houston is consistently looked over,” she added. “We’ve seen that in Harvey, Uri and our recent disasters with the derecho and Beryl. The idea for hub houses came out of Winter Storm Uri, that we were not getting help so we needed localized community, neighborhood-based resiliency centers and places of refuge and relief.”

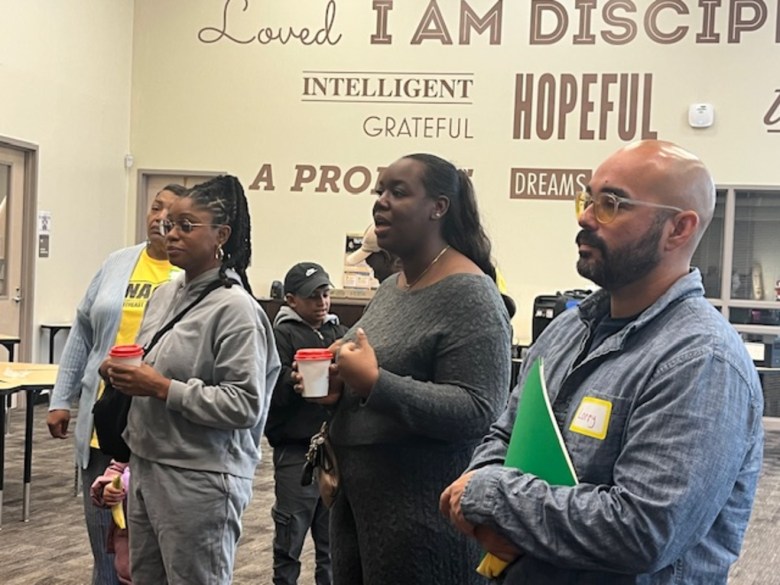

About 50 people attended a training workshop Saturday hosted by West Street Recovery and Northeast Action Collective. Credit: April Towery

About 50 people attended a training workshop Saturday hosted by West Street Recovery and Northeast Action Collective. Credit: April Towery

Guevara is a hub house block captain, meaning she distributes supplies to neighbors and has solar panels and a dual fuel generator to ensure a power source even when the electricity goes out.

She sees it as a way of paying it forward eight years after the Cajun Navy, a volunteer network of boat owners in Louisiana, rescued her from her home during Harvey. She remembers trying to find a temporary home and worrying about her lost loved ones, needed repairs and money. That’s about the time that Andrew Barley — now West Street Recovery’s director of rebuild efforts — showed up to help.

Guevara says her son advises her that she can stay home once in a while and doesn’t have to say yes to every request for help, but she knows how much it meant to her when strangers helped her rebuild after Harvey. She wants to offer that same support to others, she says.

“I do a lot of running around, and I just pray that God gives me the strength to keep on going,” she said. “When I’m out helping people wrap their pipes, because I’m older, they tell me, ‘I’ll do it,’ but I’ve got to make sure they’re doing it right.”

West Street Recovery rebuild contractor Tracy Hamblin, right, conducts a training exercise at a disaster preparedness event in Fifth Ward on Saturday. Credit: April Towery

West Street Recovery rebuild contractor Tracy Hamblin, right, conducts a training exercise at a disaster preparedness event in Fifth Ward on Saturday. Credit: April Towery

At Saturday’s event, the multipurpose room was filled with people of all ages and races. College students passed by and said hello to “Ms. Anita” as though they were attending a family reunion rather than a disaster preparedness workshop.

Guevara has lived in Houston since 1964 and was first flooded out of her home back in 2001. By the time Harvey hit, she had retired from a job in advertising sales and when she provided bank statements on her application for disaster relief assistance, she was told she had too much money to qualify for help, she said.

FEMA eventually offered less than $5,000, and BuildAid Houston assisted with remodeling and restoration, saying at the time there were more than 100,000 residents who had home damage and about 85 percent did not have flood insurance.

Hurricane season ended last month without a named tropical storm making landfall in Texas but freezes are still very much on the horizon. Winter Storm Uri happened in mid-February 2021.

Guevara, proudly wearing her yellow Northeast Action Collective T-shirt on Saturday, said she doesn’t plan to slow down her efforts to assist her neighbors.

“If I can help, I’m going to do it or I’m going to find someone else who can do it,” she said.

This article appears in Jan 1 – Dec 31, 2025.

Related