From the pretzel seller outside work to the halal cart in the corner, street food vendors make up the fabric of New York. But perhaps even their most loyal clients might not know about their history — or the current struggles they face. The exhibition, “Street Food City,” at Brooklyn’s Museum of Food and Drink, aims to change that.

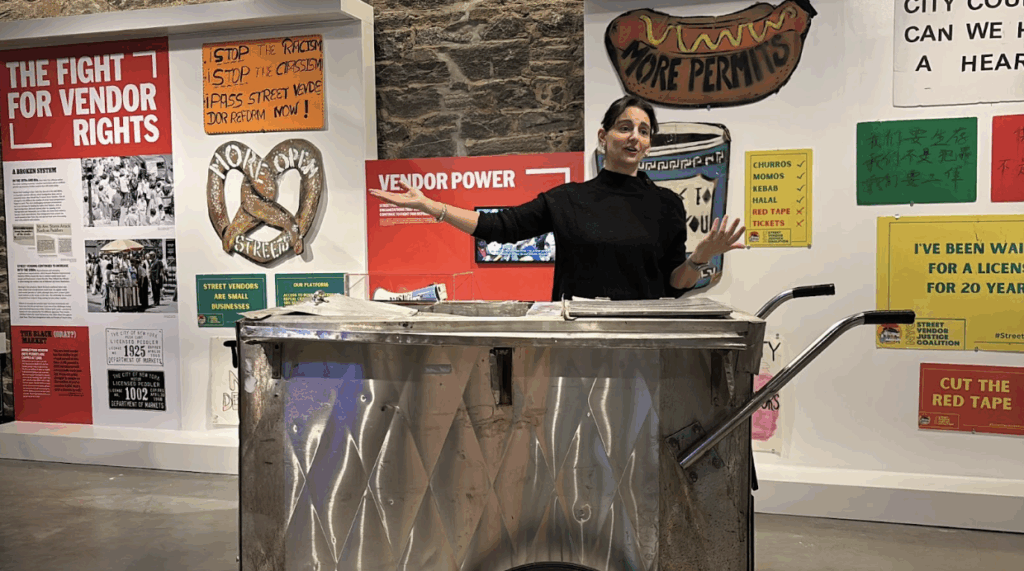

“We wanted to do this exhibition to really humanize the vendors,” said Nazli Parvizi, 40, president of the museum. The exhibition opened on Dec. 6, inviting visitors to step behind the cart and explore how street food, and the people who sell it, have shaped New York’s culture and culinary landscape for centuries.

Here are a few takeaways:

How vending funded the Underground Railroad

Street food in New York dates back to the 1600s, when baskets and baby strollers served as makeshift carts. According to Parvizi, in the early 1800s, Black oystermen started to sell “massive” amounts of oysters, helping build wealth in Black communities, especially on Staten Island. Some even helped fund the Underground Railroad. By the mid-1800s, Jewish and Italian immigrants came to the Lower East Side, where they sold cheap street food like pickles, pumpernickel bread and peanuts to feed their own communities.

“With every wave of immigration, you get a whole new set of vendors and foods,” Parvizi said. What began as a predominantly African American trade, she said, evolved into a broader immigrant phenomenon.

Who today’s vendors are

According to a 2024 report of the Immigration Research Initiative of the city’s approximately 23,000 street vendors, 20,500 are street food vendors and 96% are immigrants. Most are ages 35 to 54 and Latino, primarily from Mexico and Ecuador. About one in five is Middle Eastern. Half of all vendors are women, though many primarily cook and sell for their own communities.

About 55% speak little to no English, and many are undocumented, making them a target for policing and U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement. “There are a lot of stories you’ll hear in the exhibition where vendors explicitly told us, ‘Please don’t share our photo, please don’t share our names,’” Parvizi said.

How vendors struggle on a daily basis

Working five or six days a week for 12-plus hours, rain or shine, while pushing heavy carts, is physically draining. Two out of three vendors don’t have access to a bathroom while working.

Around 400 years of vending have created a maze of rules and regulations vendors have to navigate. Under Mayor Eric Adams, law enforcement ramped up to enforce these rules. In 2024, the police and Department of Sanitation collectively issued more than 10,000 tickets to vendors lacking proper paperwork or violating rules that advocates say are too expensive and burdensome to follow. That’s five times more than in 2019. In July, Adams vetoed a reform bill that would help decriminalize street food vendors, arguing that it would harm established businesses and pose public health risks.

Nazli Parvizi, president of MOFAD, talks about the exhibition’s “Call to Action” corner. (Credit: Ambra Schuster)

The permit problem and possible change

The biggest barrier for street food vendors remains the city’s limited vending permits, which have a waitlist of about 10 years. The only way to sell legally is to buy a license on the black market for up to $25,000 instead of a few hundred dollars.

But change may be coming: Mayor-elect Zohran Mamdani has promised to add 4,000 permits, update vending rules and address what he calls “Halalflation.” Something Parvizi is “thrilled about.”

“Street Food City” is open Thursday through Sunday, 12 to 6 p.m., at the Museum of Food and Drink in DUMBO, Brooklyn.