As a part of our 25th-anniversary celebration, we’re republishing formative magazine stories from before our website launched. This story previously appeared in Dwell’s July/August 2007 issue.

“We were so involved in the architecture that we never had time for networking,” says 79-year-old Barbara Neski, recalling the 40-year collaboration she enjoyed with her late husband, Julian. “That way we could have a career and children too. We were always a close-knit family.” Together they designed more than 35 houses in a style that was at once urgently urban while still being approachable and sensitive to their rural sites. While grounded in the geometry of European modernism, their best designs reflected both the landscape and the social milieu that were unique to the Hamptons, where 25 of their much-lauded vacation homes were built.

The sharp-edged, boxy forms with roof decks, sun courts, shifting planes, and multiple levels were very much an expression of the times. Exterior walls of white or gray-stained cedar siding served as foils for the play of light and shadow. Ramps replaced conventional stairways, evoking a sense of perpetual motion and perpetual expectation: Le Corbusier’s idea of la vie sportif reimagined for the television age. Unlike some of their better-known contemporaries, the Neskis rarely, if ever, repeated themselves.

Barbara, known as “Bobbie” by close friends, was born Barbara Goldberg in 1928 and grew up in Highland Park, New Jersey. In 1948, during her third semester at Bennington College, she discovered the joys of good design—she was taken by the elegance of the butterfly roof of the nearby Robinson House by Marcel Breuer in Williamstown, Massachusetts—and knew she wanted to be an architect. “I didn’t know that a house could be a work of art,” she confesses. “Breuer was an eye-opener.”

Barbara finished Bennington in 1949 and went on to Harvard’s Graduate School of Design (GSD), then under the directorship of Walter Gropius. Women architects were still an oddity then, and Barbara’s father warned her to take up shorthand just in case. While she never studied directly under Gropius, Barbara remembers him being a very gentle man, which wasn’t always the case with GSD faculty. One of her teachers, Hugh Stubbins, refused to take her seriously. “He would come around during crits and completely ignore me,” recalls Barbara. “He didn’t even look at my drawings.” She was, however, accepted by the other students. “All the guys wanted to help me. I had a lot of boyfriends.”

She finished Harvard’s three-year program in two, and in 1952 started in the New York office of José Luis Sert, where she worked on urban plans for Bogotá and Havana. “There were only a few of us in the office and everything was charrette. We’d always work through the night.” It was also at this time that she met her future husband and design partner, Julian Neski, who was also working for Sert. They married in December of 1953 while they were both working in Marcel Breuer’s office. “Breuer always liked women as ‘things’ hanging around the office,” she says. There, Barbara developed plans for a factory in Canada, a house in Connecticut, and the new library at Hunter College. She stopped working for Breuer in 1957, pregnant with her first child, Steve. “I changed his diaper on our drafting table,” she recalls.

By the early ’60s, the Neskis had established their own firm. “We shared everything and presented ourselves to clients as a team,” says Barbara, but clients often had a more conventional view. “Invariably the wife would direct her questions about interiors to me and the husband would bring up money matters with Julian.”

The Neskis’ clients weren’t merely escaping their weekday pressures; they were out to make a statement, transplanting their edgy energy from the city to the beach. The Simon House (Remsenburg, 1972) was just such a reflection of its owners’ careers. Peter Simon starred on a soap opera and his then-wife, Merle, was a singer/dancer on Broadway. The house’s 11 rooms were stacked in spiraling order, each on its own level. As one progressed up the central staircase, the ceilings got higher and the views expanded, culminating in a panoramic view of the ocean. “It opened up nicely as a stage set,” says Barbara. “We liked to imagine Merle dancing down those stairs while her husband played the piano on a different level.”

Barbara and Julian were equals in the studio. “We never had an argument about design,” says Barbara. “We usually knew exactly what the other had in mind.” Julian always tried to get the right proportion. He would do a tiny sketch and then Barbara would blow it up and make it work as a building. “I’m a puzzle freak—I love crosswords and jigsaw puzzles—so I worked more on the plans and how everything fit together.” With the Simon House Julian had the idea of squares within squares, but it didn’t work until Barbara turned it all at a 45-degree angle and stacked the levels into an ascending sequence.

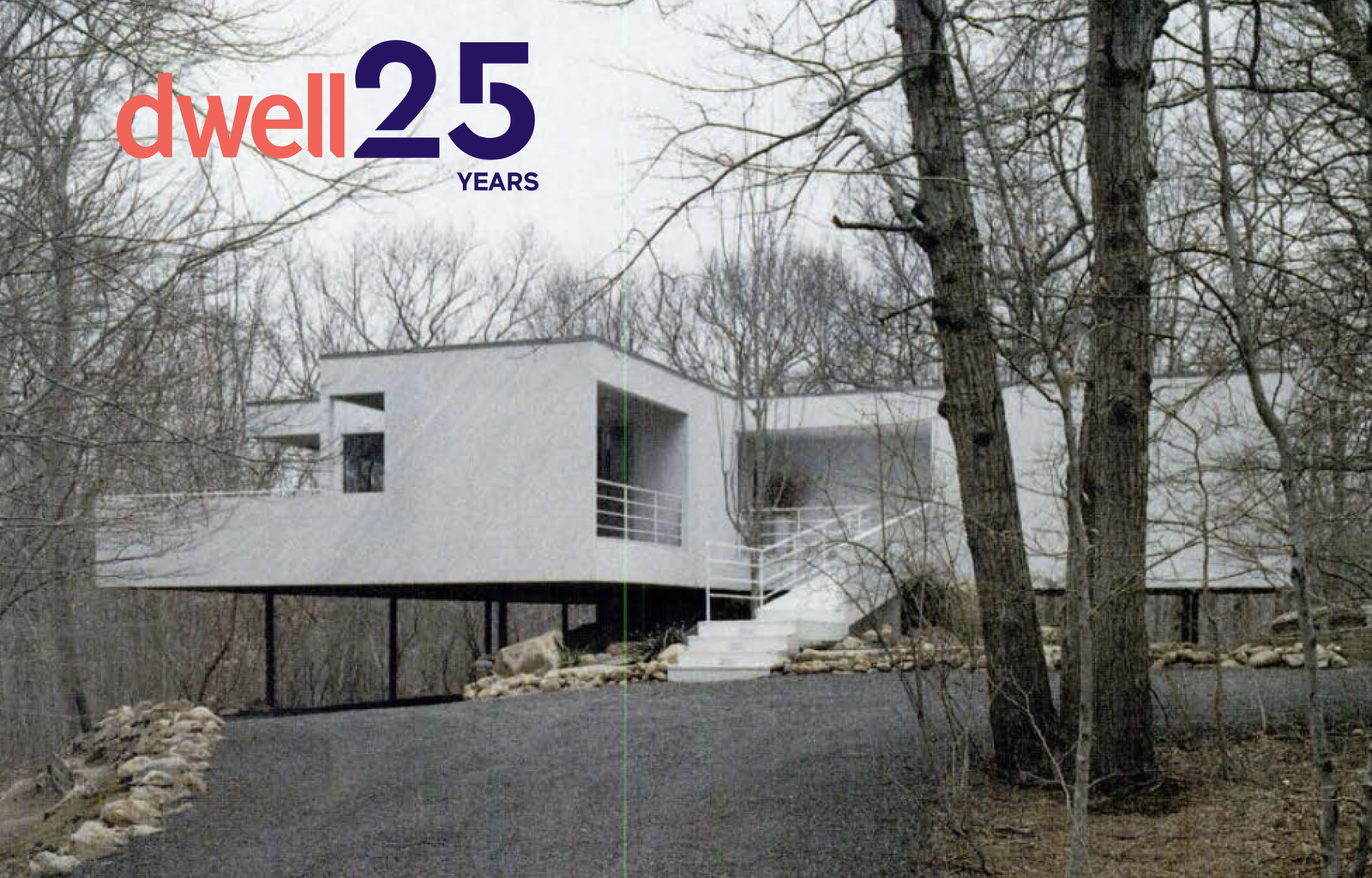

The Formby House (1980) has all the moves of a classic Neski beach house minus the million-dollar views—it’s actually a 10-minute walk to the nearest beach. Originally built for a corporate headhunter, the house hovers on narrow pilotis above a thickly wooded lot in Amagansett. Barbara envisioned this as the house’s compositional thrust and an early rendering shows how supporting columns, railings, and window mullions echoed the forms of surrounding trees. Discrete volumes were wrapped in cedar siding punctured with large openings. An open deck cantilevered out to one side.

By 1995, however, when Scott and Kathy Formby, two young fashion designers, came across the house, it was badly in need of repair. “When we first saw the house, we knew whoever designed it was on the same wavelength,” says Scott. “We shared the same values, the same aesthetics.” They went with their instincts and decided to buy it on the spot. Instead of hiring another architect, they sought out the Neskis, asking them to help update the house. “These were the coolest people we ever met,” recalls Kathy. “Barbara was wearing a big old sweater. At first we were nervous, like Mom and Dad were coming over, but we bonded with them right away.”

The outside, which had been silvery gray, was stained white and the outdoor shower was removed from the front. Interior spaces were also painted white to create a neutral setting for the Formbys’ collection of midcentury furniture. The hollow-core doors were replaced with solid ebony-stained ones. Woven-seagrass wallpaper hangs in the bedrooms and a bed of smooth black stones lies on the bathroom floor.

“The house is so beautifully placed,” says Kathy. “There is the light shimmering through the trees. It’s like you’re cloaked in trees. In spring we have the dogwoods hanging over the deck, and it feels as if they were blossoming right in the middle of the living room.” Neski houses were never just plunked onto the site like abstract objects, but were intimately connected to the natural landscape. Openings and decks were determined by view lines and prevailing breezes.

Looking back, Barbara is delighted with the work the Formbys have done. “They really captured the original spirit of the house. Their enthusiasm is wonderful.”

Throughout their four decades of practice, Barbara and Julian kept their office small, partially by choice, retaining a one-to-one relationship with each and every project, drawing all the details themselves. After Julian died in 2004, the architectural practice slowed somewhat, but Barbara continues to work on apartment and office interiors in Manhattan. Though things have gotten easier for women working in architecture, Barbara is always cognizant of the trail she helped blaze. “It wasn’t easy being a woman architect in those days,” says Barbara. “I wasn’t supposed to know anything unless it was about the kitchen or the furniture.”

See more from the Dwell archive on US Modernist.