The order that closed the nation’s founding river was bureaucratically frank.

The Virginia State Board of Health had become aware of conditions in the James River, from the fall line at Richmond to its mouth at the Chesapeake Bay, “which constitute a potential danger to the health and welfare of the citizens of the Commonwealth due to the unauthorized and unwarranted release or discharge of Kepone (chlordecone) to the environment.”

So, on Dec. 17, 1975, then-Gov. Mills Godwin took to a dais to announce an unprecedented measure: commercial and recreational fishing in the James was banned, so that citizens “may be relieved of any unnecessary concern about the possible hazards involved,” he said.

Restrictions on fishing weren’t completely phased out until 1988.

Fifty years after the river’s closure, Virginia’s worst environmental disaster — one that sickened scores of citizens and crippled a vital industry — marks a nadir in the state’s history. Yet for all the hardship Kepone contamination imposed on Virginia and its residents, the fallout from the disaster had some silver linings, among them grassroots environmental advocacy and changes to policy and procedures designed to prevent ecological calamity.

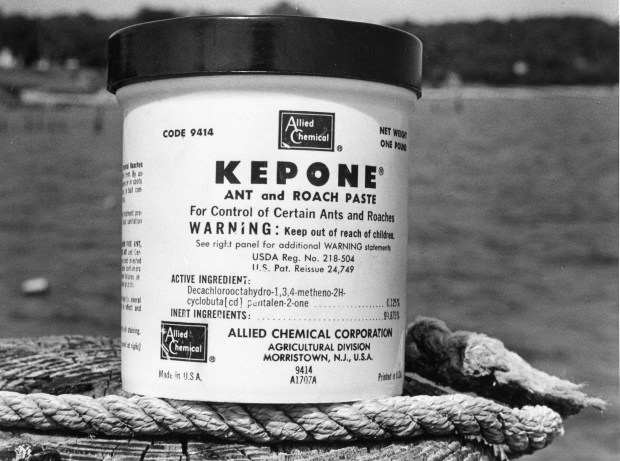

Kepone was the brand name for chlordecone, a highly toxic synthetic insecticide that was produced from 1966 until 1975 at a chemical plant next to the James River in Hopewell. The plant discharged its toxic production wastes directly into the river, creating an environmental disaster that lasted decades. (Daily Press file)

Kepone was the brand name for chlordecone, a highly toxic synthetic insecticide that was produced from 1966 until 1975 at a chemical plant next to the James River in Hopewell. The plant discharged its toxic production wastes directly into the river, creating an environmental disaster that lasted decades. (Daily Press file)

Kepone was the brand name of the pesticide chlordecone, manufactured to control the Colorado potato beetle and the banana weevil, according to University of Akron history professor Gregory Wilson, author of “Poison Powder: The Kepone Disaster in Virginia and its Legacy.” Chlordecone was a carcinogen and endocrine disruptor that could have devastating effects in humans and animals, said Wilson, who grew up in Newport News.

Allied Chemical Corp. manufactured Kepone in Hopewell, an industrial town on the bank of the James River about 15 miles south of Richmond. In the 1960s and 70s, Allied Chemical subcontracted some of its production of Kepone, and among the other firms that made the pesticide was Life Science Products, also in Hopewell, run by two former Allied Chemical executives.

At Life Science Products, employees manufactured Kepone largely without the use of protective equipment. Chlordecone dust floated freely in the air and coated all the surfaces of the workspace. Exposure caused many workers to experience tremors, among other serious health problems.

Life Science Products also discharged its industrial waste in several places, including in-ground burial pits, a local landfill and Hopewell’s sewer system. According to Wilson, Life Science Products’ disposal of its Kepone-tainted waste went undetected because Hopewell officials were not reporting the company’s discharge into its sewage treatment system.

University of Akron history professor Gregory Wilson, who wrote “Poison Powder: The Kepone Disaster in Virginia and its Legacy,” grew up in Newport News. (Courtesy/Greg Wilson)

University of Akron history professor Gregory Wilson, who wrote “Poison Powder: The Kepone Disaster in Virginia and its Legacy,” grew up in Newport News. (Courtesy/Greg Wilson)

State and federal officials knew something was amiss when a blood sample from a Life Science Products employee was sent to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and registered a level of Kepone that was off the charts.

State water regulators also learned via an offhand conversation that Life Science Products’ waste was going into Hopewell’s sewage system and from there into the watershed. Subsequent investigations revealed that Allied Chemical had also been dumping Kepone into the James River.

By the time the discovery of contamination prompted state and federal officials to act, there was an estimated 20,000 to 40,000 pounds of Kepone in the James River.

Mike Unger, a retired Virginia Institute of Marine Resources professor who authored a 2017 report on Kepone, tested thousands of samples of sediment and organisms in the James River and surrounding waters. He said the largest concentrations of Kepone in the river were not directly in front of Hopewell. Instead, much of it settled in downstream areas where there was more energetic movement of the water.

And Kepone was not only in the bed of the river. Aquatic plants and animals also ingested the toxin.

The closure of the James River and its tributaries to fishing and shellfishing was a blow to commercial watermen. Contemporary figures estimated that the ban cost the fishing industry $18 to $20 million — roughly in the $80 million range in modern dollars.

J.C. Hudgins of Mathews County is president of the Virginia Waterman’s Association, a trade advocacy group. Hudgins was working on a tugboat at the time but remembers how devastating the closure was for local watermen. They already existed hand-to-mouth and the closure put many over the edge of insolvency.

“Nothing’s given to you out there,” he said. “You have to go out there and get it. Kepone had a huge impact on many watermen.”

The Kepone disaster helped spur the creation of the James River Association, which works to protect the waterway and its tributaries, said Bill Street, the organization’s executive director, pictured here. (Courtesy/James River Association)

The Kepone disaster helped spur the creation of the James River Association, which works to protect the waterway and its tributaries, said Bill Street, the organization’s executive director, pictured here. (Courtesy/James River Association)

Allied Chemical, which was found liable for the contamination, paid some $30 million in criminal and civil lawsuits filed after the disaster (Life Science Products was bankrupt when it ceased operation in 1975). For violating environmental laws, Allied Chemical ultimately paid a $5 million fine and agreed to provide $8 million to establish the Virginia Environmental Endowment, which was founded in 1977.

That seed money has blossomed into untold riches in terms of environmental protection, according to Joe Maroon, president of the endowment. The organization has made more than 1,500 grants that, along with matching funds, have provided over $130 million to protect Virginia’s natural resources, partnering with organizations on significant environmental projects around the commonwealth.

The Kepone disaster also prompted concerned citizens to act. In 1976, the James River Association, which works to protect the waterway and its tributaries, was formed around a kitchen table, said Bill Street, the organization’s executive director. Ordinary people living along the river realized that if someone didn’t take measures to preserve it, all could be lost.

Striped bass or rockfish are one of the fish species that researchers at the Virginia Institute of Marine Science examined for Kepone levels. (Courtesy/VIMS)

Striped bass or rockfish are one of the fish species that researchers at the Virginia Institute of Marine Science examined for Kepone levels. (Courtesy/VIMS)

The Kepone disaster was “rock-bottom” for the James River, according to Street, but 50 years later, the JRA works with partner organizations to improve the watershed, such as informing policy matters, working with landowners on shoreline enhancements, and helping diminished species such as sturgeon return to historic levels.

But for all the progress that JRA has made over the last 50 years, there’s still a lot of work to be done, Street said. The organization currently gives the river a grade of B in its State of the James Report. “We want to hit a grade A James River,” he said. “The James is the largest source of drinking water in Virginia, and we believe that everyone deserves to have grade A drinking water.”

The disaster also led directly to environmental laws designed to prevent another such catastrophe from occurring, such as the Toxic Substances Control Act of 1976 and amendments to the Clean Water Act.

Today, people whose livelihoods are directly tied to the water are hypervigilant about threats to the health of the Chesapeake Bay, according to Hudgins of the Virginia Waterman’s Association. Fifty years ago, Kepone taught watermen that if they don’t fight aggressively for protections, threats can arise undetected. Pollutants such as PCBs continue to pose dangers to public health, he said.

In more recent years, Hudgins and his colleagues have been lobbying to regulate the use of biosolids on farm fields, which leach toxins known as PFAs into the bay.

What was so pernicious about Kepone is that it caught Virginians off guard, said VIMS’ Unger. Nobody knew that Kepone was a threat, so no one thought to look for it. The crisis led to a unique monitoring program that detects unknown compounds.

The James River today as seen from Old City Point Park in Hopewell, where the Kepone spill originated in 1975. The largest concentrations of Kepone didn’t settle in front of Hopewell, but in downstream areas. (James W. Robinson/The Virginia Gazette)

The James River today as seen from Old City Point Park in Hopewell, where the Kepone spill originated in 1975. The largest concentrations of Kepone didn’t settle in front of Hopewell, but in downstream areas. (James W. Robinson/The Virginia Gazette)

The level of Kepone found in organisms that live in the James River steadily decreased over time, until it was deemed to be at an acceptable level, Unger said. Much of the Kepone in the James River is still there, although it’s buried under perhaps feet of sediment and is no longer readily available for fish and plants to take up.

And while Virginians need not worry about the Kepone buried under sediment, other places are struggling with the pesticide’s persistent legacy. “It was designed to last a very long time and be effective,” Wilson said.

While Kepone was banned in the United States in 1978, its use continued on banana plantations in the French Caribbean islands of Martinique and Guadeloupe into the 1990s and possibly into the 2000s, according to Wilson. Communities there are navigating public health crises that manifest in high rates of cancer and low birth weights.

When he first started researching his book, Wilson said he thought Kepone was a Virginia story, but soon realized the disaster had global implications. And from that he understood that Kepone taught everyone, not just Virginians, a lesson about the outcomes of ignorance.

“When it comes these substances, we have to be vigilant — how they are used, where they are used. The negative health consequences can be significant.”

Ben Swenson, ben.swenson05@gmail.com