The steel-throated bird of paradise has feathers so intensely black they seem to swallow light. Inspired by this wonder of nature, scientists have developed a fabric that redefines the limits of darkness. With its nanoscale structure that captures light, it promises stunning possibilities in fashion, design, and cutting-edge technology.

We perceive color through the dance of light and matter. Sunlight contains every wavelength in the visible spectrum, but when it strikes an object, some wavelengths are absorbed while others bounce back. The ones reflected toward our eyes are what our brains interpret as color. In short, the shade we see depends on an object’s chemistry and electronic structure — the keys to which wavelengths are absorbed or reflected.

Ultrablack: almost total light absorption

Objects that absorb nearly every wavelength appear black. But not all blacks are created equal — some are far deeper than others.

The feathers of the magnificent Ptiloris magnificus, or steel-throated bird of paradise, are an exceptional case. Scientists call it “ultrablack” when less than 0.5% of light is reflected — a level of absorption that makes its plumage look like a hole in reality itself.

The steel-throated bird-of-paradise has inspired researchers at Cornell University. © Paul Maury, Cornell Lab of Ornithology

Studying those feathers inspired researchers to design new ultrablack textiles at a fraction of the cost of existing materials. Previous breakthroughs include Vantablack, a British invention from 2014 that absorbs 99.96% of light, and an even darker material created at MIT in 2019, which pushes absorption to 99.995%. It doesn’t get much blacker than that — or so we thought.

Vantablack is one of the deepest blacks ever produced. © Surrey NanoSystems, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 3.0

Nanofibrils that trap light

Producing these materials, however, is notoriously difficult and expensive. So a team from Cornell University decided to take another path. They dyed a piece of white merino wool with a synthetic melanin polymer called polydopamine, then placed it in a plasma chamber to form nanometer-scale fibrils. These microscopic fibers — modeled after the bird’s feathers — bounce light between them until it can’t escape, achieving an impressive 99.87% absorption.

“Light essentially bounces from one fibril to another instead of reflecting outward,” explained lead author Hansadi Jayamaha. “That’s what creates the ultrablack effect.” Unlike the natural feathers, which lose their depth when viewed from an angle, Cornell’s fabric keeps its rich darkness even when tilted up to 60 degrees.

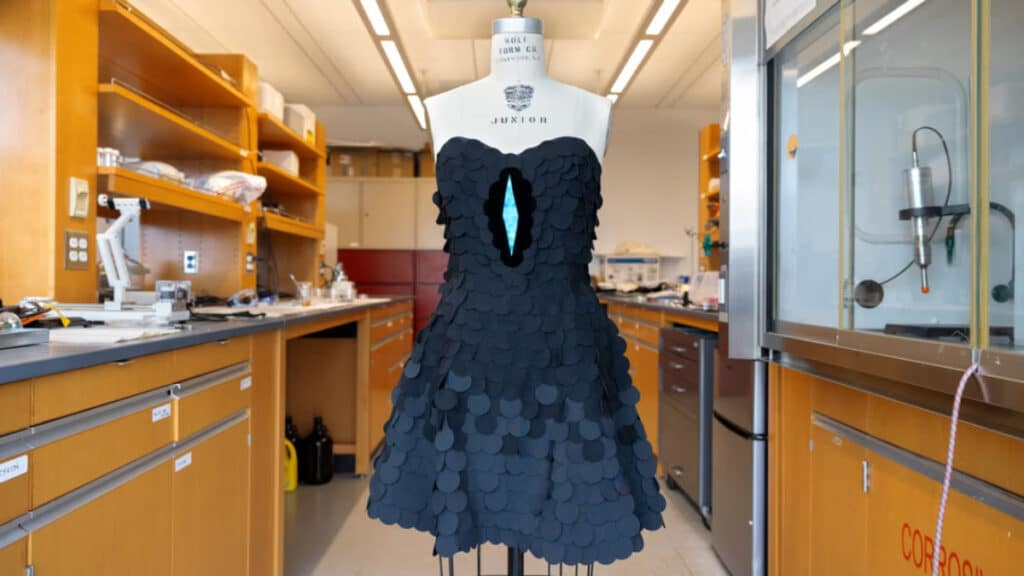

Cornell University fashion student Zoe Alvarez created a dress using several shades of black, including the new ultrablack (center). © Ryan Young, Cornell University

Endless potential applications

Beyond the world of haute couture and avant-garde design, this new fabric could transform several industries. In solar thermal systems, for example, its ability to absorb nearly all incoming light could dramatically boost heat conversion efficiency.

The researchers also envision uses in thermal camouflage, photography, imaging, optics, and astronomy. If adaptable to different surfaces, this material could line the interiors of cameras or telescopes, reducing glare and light “noise” to reveal clearer, purer images of the universe.

Morgane Gillard

Journalist

As a child, I dreamed of being a paleontologist, an astronaut, or a writer… and ultimately, my heart led me to geology. After years of studying to gain deep knowledge, I now share it with you, the readers of Futura!

Looking back, I realize that my passion for Earth and science in general started very early! My first spelunking expedition was at the age of 4, my first scuba dive at 7, fossil hunting all across France, nighttime outings to watch the stars… With a father who was a chemistry teacher and an avid cave diver, and a mother who was the first female commercial diver in France, my childhood was filled with adventure and discovery! One memory in particular stands out: observing the Hale-Bopp comet in 1997, in the middle of the night, standing in a field while my parents whispered the countdowns for the exposure times to photograph that strange celestial object lighting up the sky. That image is forever etched in my memory, a moment filled with a certain magic—and even today, I still get chills when I gaze up at the stars. Head in the stars, feet on the ground. It was probably during our travels in an old Volkswagen van, between Andalusia and the barren lands of the North Cape, that I discovered the incredible beauty of nature and the stunning diversity of landscapes our planet has to offer.

Discovering Earth and Its Inner Workings

After high school, pursuing scientific studies felt like a natural choice, so it came as no surprise when I enrolled at university for a full degree in Earth Sciences. But I struggled to stick to just one field. During my studies, I explored all areas of geoscience: from geodesy to electromagnetism, from mineralogy to field geology… I loved learning about Earth and its complexity, its beauty, its strength, and its fragility. So when I was offered the chance to start a PhD in geodynamics in 2011—studying the development of the Australian and Antarctic margins—I didn’t hesitate. More things to learn and discover!

One of the most fascinating aspects of geosciences is how you juggle both vast timescales and spatial scales. You never stay still—you’re constantly zooming in and out. In a single day, you might shift from looking at the oceanic crust to analyzing a tiny mineral. You might be discussing tectonic plate movements and then chemical interactions between minerals. What could be more exciting?

From Continent to Ocean: The Incredible Journey of a PhD

Over those three years, I gradually specialized in seismic interpretation. Like a detective, I learned to read those striped black-and-white images and reconstruct a story—the story of plate tectonics and the opening of an ocean. Specifically, I worked on the development of detachment faults in the continent-ocean transition zone and the sedimentary record they produce. I had the opportunity to present my work at many international conferences and built a strong scientific identity. Three years of hard work, amazing discoveries, and incredible encounters shaped me into who I am today. After defending my thesis in 2014, I completed several years of postdoctoral research with CNRS and in collaboration with oil companies interested in these increasingly strategic zones for petroleum exploration.

Science, Always and Forever

But… academia is demanding, requiring full-time commitment—something not always compatible with starting a family. So I made the tough decision to shift career paths and turned to scientific writing. It turned out to be a great choice, as it allows me to keep talking about science, especially geology. Working with Futura is a real opportunity because it lets me share the world of Earth Sciences—an often-overlooked field—with a broad audience. After all, what could be more important than understanding the planet we live on?