In Slate’s annual Movie Club, film critic Dana Stevens emails with fellow critics—for 2025, Justin Chang, Alison Willmore, and Bilge Ebiri—about the year in cinema.

Hi, guys!

Funnily enough, I was already mulling over my favorite moments from this year’s movies before I got your last post, Alison. But damn it—you included words like hopeful and joy, and that is decidedly not the vibe that dominates the scenes and shots I’m thinking of.

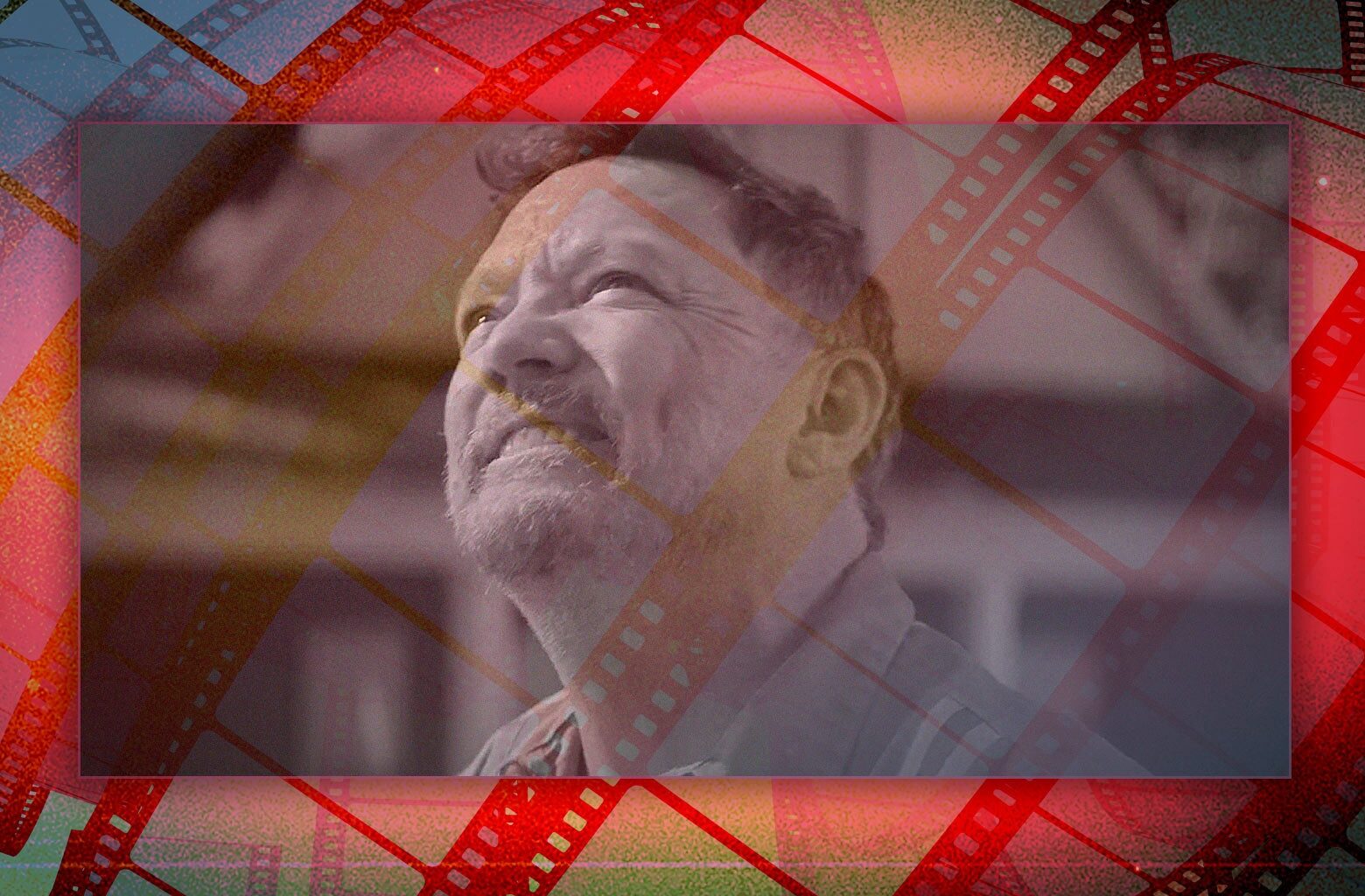

Especially the first one, which largely has to do with one tiny, isolated performance. Matthew Lillard’s monologue in Mike Flanagan’s The Life of Chuck is the actor’s only scene in the film, and it’s quite short. (Naturally, one of the reasons I’m thinking about it nowadays is because of that stupid kerfuffle this month over Quentin Tarantino bad-mouthing Lillard and several others during a podcast interview.) In it, Lillard’s character is just marveling at how quickly life on Earth appears to be unraveling. The Life of Chuck’s first section is pretty much a depiction of the apocalypse, as we witness what appears to be the end of, like, everything. (The film takes some wild turns after that.) As Lillard goes through a litany of all the catastrophes that have happened—wars, riots, governments overthrown, volcanoes in Germany—he speaks with a combination of bemused disbelief and abject grief, at times seeming to break into laughter only for it to turn out he’s actually crying. This is not an actor I tend to think of as having a lot of range, but he goes through pretty much every single human emotion there is in the course of about two minutes, all while the camera remains close on his face. It’s magnificent, a bravura feat of acting—in a film that eventually goes to all sorts of other places, so that by the end we’ve almost forgotten that its opening act was a disaster flick.

I also find myself thinking of a brief bit—a shot, really—in Sierra Falconer’s Sunfish (& Other Stories on Green Lake), a marvelous standout from this year’s Sundance Film Festival that was, for my money, the directorial debut of the year. The movie has an anthology structure, and in the first episode, we watch 14-year-old Lu (Maren Heary) as she winds up stuck at her grandparents’ lake house while her free-spirited mom elopes with a somewhat scuzzy boyfriend. Roaming the lake, Lu discovers a stray loonlet after a storm, and she and her grandparents nurse the baby bird back to health. Lu herself feels left behind, of course, by her own mom. The moment I’m thinking of occurs after the loonlet’s mother finally shows up: We see the young girl berating the older bird for abandoning its offspring. Now, this might sound heavy-handed, especially the way I’ve just described it! But the way Falconer shoots it demonstrates real cinematic intelligence. The camera remains some distance away, and we don’t even really hear what Lu is saying to the bird; we catch just a word or two. The director thus acknowledges the predictability of the girl’s little outburst—which makes it that much more heartbreaking. The moment combines both Olympian remove and intimate humanity, and it does so playfully. I haven’t been able to stop thinking about it since I saw the picture in early January. I tend not to be crazy about anthology-style films, but Sunfish really won me over, and Falconer feels like a director we’ll be hearing more from in the future.

And then of course there’s Hamnet, a movie I guess you folks didn’t much care for, but which stands near the very top of my best-of list, alongside Train Dreams and Caught by the Tides. There are several incredible moments in Hamnet, including a final outreach of hands in the very last scene that Justin already mentioned and which never fails to generate an audible shudder with audiences whenever I see the movie. But the moment I’m thinking of comes some time before that, when Paul Mescal’s Will Shakespeare is rehearsing the “Get thee to a nunnery” speech from Hamlet with his actors, and keeps berating them to do it again, because they’re not getting it right. Finally, he charges in and does it himself, and Mescal delivers Shakespeare’s words with such spittle-flecked self-loathing that he practically redefines one of the better-known soliloquies in English literature right before our eyes. (By the way, while I’m very happy that Jessie Buckley is getting a ton of acclaim for her extraordinary performance in Hamnet, I am a little shocked that Mescal has gotten so little traction.)

I think I actually let out a little giggle the first time I watched Matthew Lillard’s monologue, because I was so excited by what I was witnessing.

As much as I enjoyed One Battle After Another, I didn’t quite love it as much as everyone else has. But there is one moment right at the very end that has really stayed with me, when Leonardo DiCaprio’s Bob Ferguson is finally reunited with his daughter, Willa, played by Chase Infiniti. We’ve already had all the crazy chases and the (rather convenient) shootouts and all that other spectacular stuff. Willa has just killed a professional assassin. Now she’s got her gun trained on her dad and looks ready to shoot him—almost as if she doesn’t recognize him, even though it’s been only, I think, a day since they were separated. He yells their preestablished passwords, but it doesn’t seem to have any effect at first. I love the way Infiniti plays this scene. We see the anguish and confusion on her face. Here’s a young woman who has just found out that her mother, who she thought was a dead hero, is in fact alive and an informer, and that her father isn’t really her biological father. Yes, Bob is still the man who raised her, who has been there for her all these years. But who is he really? Her whole life has been a lie, her world has been upended, and she no longer has any idea whom to trust. The actress doesn’t have to say any of this; we see it in her face, and we understand. That’s acting!

These are all bleak, dark moments, but they do make me happy—so maybe I am answering the question in the right spirit after all. One can always find joy and hope in great artistry. That’s sort of the point of art. I think I actually let out a little giggle the first time I watched Lillard’s aforementioned monologue, because I was so excited by what I was witnessing.

Following up on all your lovely tributes to Rob Reiner, I do want to say something about him and other directors who had that “anti-auteurist” touch that Justin mentions. At the risk of repeating what everyone has said, I’ll note that losing Reiner feels like a direct hit on Generation X’s memory palace. Stand By Me was the talk of my eighth grade class. (And it happened to come out right as we were all getting into Stephen King.) I’ll always remember going with my mom to see The Princess Bride on opening night, because I had just gotten glasses a week earlier, and I forgot my glasses at home, so I initially experienced that movie as a bit of a blur. (And of course my mom berated me all night for forgetting my glasses.) A Few Good Men is one of a small handful of movies I rewatch about once a year. I even remember how stunned we were when North bombed; it seemed at the time as if Reiner could do no wrong.

One of my college roommates once observed, with only a slight hint of snideness, “Isn’t it weird that our three most successful directors right now are Laverne, Opie, and Meathead?” Referring, of course, to Penny Marshall, Ron Howard, and Rob Reiner, three regular hitmakers who came up as iconic TV actors (and whose paths often crossed—Reiner and Marshall were actually married for a while). I believe he said this sometime in 1992, after we’d seen Marshall’s A League of Their Own. There were obviously other directors during this period who were regularly producing a wide spectrum of financially successful midrange studio pictures—your Robert Zemeckises, your Barry Levinsons, your Chris Columbi, a couple of whom had come up through the Steven Spielberg Blockbuster Mentorship Program—but perhaps their days in the salt mines of network television gave Reiner and Co. a certain facility with actors and a respect for the more mundane aspects of their craft.

I recalled my old roommate’s words often in 2025, because I spent a decent chunk of the year delving back into Howard’s filmography for a big interview I did with him. (By the way, he hates being called Opie.) It was quite wonderful revisiting all of those movies, many of which had been huge hits in their day and some of which are classics now. Howard didn’t quite have the uninterrupted run of iconic bangers that Reiner did, but he’s probably had the longer, deeper run. (And his Imagine Entertainment occupies a place in the industry not entirely dissimilar to that of Castle Rock.) His broad filmography encompasses massive hits like Splash, Cocoon, and How the Grinch Stole Christmas, as well as acclaimed dramas like Apollo 13 (which got an IMAX rerelease this year and is, believe me, even better than everyone remembers), A Beautiful Mind, Cinderella Man, and Frost/Nixon. He continues to make good films too: The excellent Thirteen Lives sadly got the royal Prime Video streaming shaft in 2022, and the wonderfully wild and intense Eden got a relatively small release this year.

Alison Willmore

The Scariest Part of Weapons Is What It Refused to Explain

Read More

As much as I’ve enjoyed these filmmakers’ work over the years, I probably also held them at a certain remove as a young film snob, precisely because they were popular, mainstream, and versatile. Alison, you put it perfectly when you say that Reiner’s films were “such load-bearing parts of popular culture, so influential and beloved in their respective genres, that it’s easy to forget that they weren’t always there and that someone had to make them.” And these filmmakers, although they were highly recognizable as celebrities, so rarely tooted their own horns. (Maybe this too was a product of their having been TV stars, back when “TV star” was a term of borderline mockery.)

Because they hop genres and tones, we don’t really think of these directors as having any distinctive style or unifying themes … but that turns out not to be true. Maybe they haven’t been auteurs in the traditional sense. But watching their movies together over a more condensed period of time, one gains an appreciation for their directorial touch and their sensibility. That happened to me with Howard’s work: I realized that his movies have a vivid sense of place, and they’re often about communities under extreme pressure. Reiner’s films, meanwhile, often portray characters struggling with their own, sometimes-outdated codes and attitudes—be those preconceived notions of male–female relations, ideologies, or beliefs in institutions. (It might be why he made a number of films about lawyers and politicians.) These directors haven’t generally been writers, but they’ve worked closely with writers, and they often have had the power to shape their scripts—especially in a Hollywood that gave them the time and space to develop these movies properly, instead of forcing them to cut corners and rush things into production. Maybe the reason why these filmmakers’ works aren’t quite hitting the way they used to is because that Hollywood doesn’t really exist anymore.

Which means that I’ve now gone on and on and finally made my way back around to the same theme we’ve been talking about all along—a rapidly changing industry and our own constantly shifting relationship to it, as both critics and movie-loving civilians.

Still, they want us on that wall. They need us on that wall.

Bilge

Read all of the entries in Slate’s 2025 Movie Club.

Get the best of movies, TV, books, music, and more.