All major discoveries in cosmology underline the maxim that the universe is not only stranger than we suppose but that it is stranger than we can suppose. The latest example of this is a study by researchers at the Yonsei University in South Korea that said the expansion of the universe is slowing down.

The study, published in Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society of November 6, is in sharp contrast to the standard model of the universe, called Lambda-Cold Dark Matter (LCDM), which speaks of an accelerating universe.

Mysterious force

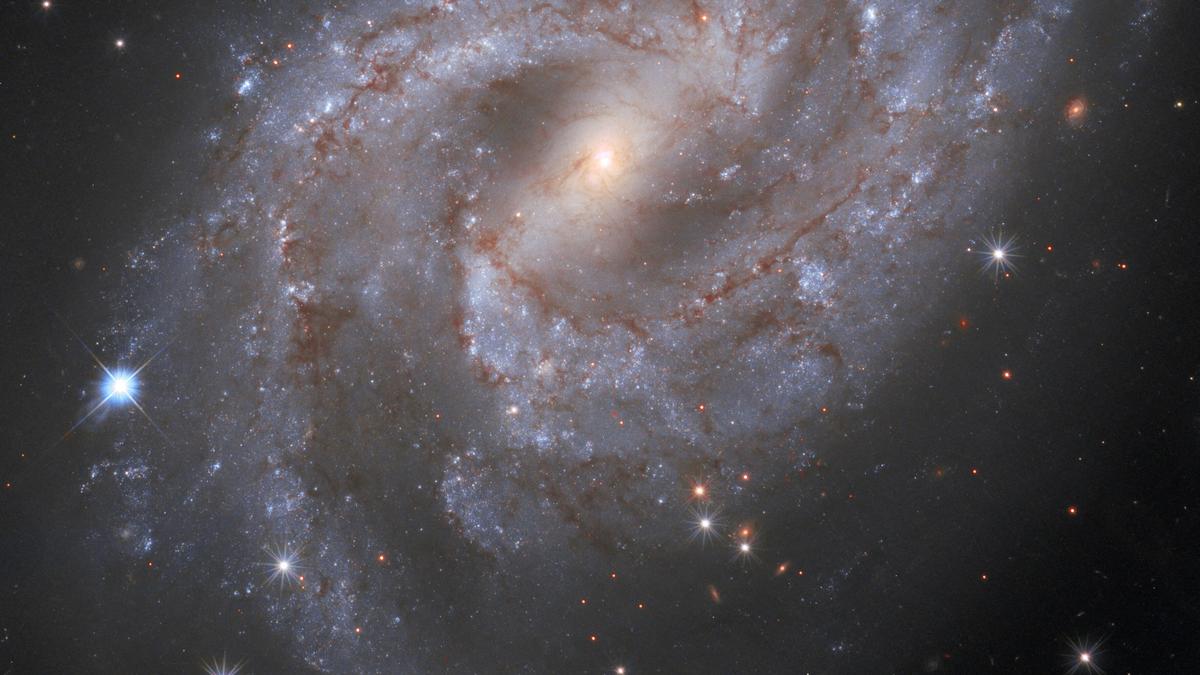

Accepted theory says the universe began about 13.8 billion years ago from a single, infinitely dense point that exploded cataclysmically in a ‘Big Bang’, leading to the formation of matter, energy, and space. As the explosion spread rapidly, it engendered subatomic particles such as protons, neutrons, and electrons before matter collapsed under gravity to form galaxies, stars and planets.

While the American astronomer Edwin Hubble confirmed that the universe was expanding in the 1920s, cosmologists conjectured that gravity must have also slowed down the expansion at some point. This is why they were surprised when, in 1998, astronomers who were measuring the distances to faraway galaxies using the light from exploding stars called Type Ia supernovae concluded that 9 billion years after the universe began, its expansion actually gained momentum.

They figured the impetus came from a mysterious force known as ‘dark energy’, which makes up about 70% of the cosmos. In 1917, Albert Einstein had proposed that its effects can be represented in equations by the cosmological constant lambda (Ʌ).

Dramatic twist

For proving that the expansion of the universe had indeed speeded up, three scientists — Saul Perlmutter, Brian Schmidt, and Adam Riess — were awarded the 2011 physics Nobel Prize. The trio and the teams they led had calculated the distances to Type Ia supernovae by using their apparent brightness as “standard candles” and measuring the redshift, i.e. the stretching of light due to the expansion of the universe. This helped them determine the speeds at which different parts of the universe were receding from the earth.

Their data showed that the universe was accelerating as dark energy forced galaxies apart ever faster. An analogy astronomers often use to illustrate this is the way raisins in rising bread dough move away from each other. Thus, in the LCDM model of cosmology, gravity binds planets, stars, and galaxies together, while the anti-gravity properties of dark energy push galaxies further away from each other, driving the universe’s expansion.

The Yonsei University study introduced a dramatic twist to this cosmic tale by suggesting that dark energy may actually be weakening, putting the brakes on the universe’s acceleration.

“Our study shows that the universe has already entered a phase of decelerated expansion at the present epoch and that dark energy evolves with time much more rapidly than previously thought,” Yonsei University astronomy professor Young-Wook Lee, who led the study, said.

The findings tie in with similar data from the Dark Energy Spectroscopic Instrument (DESI) in the USA: that Type Ia supernovae may not be the universe’s “standard candles” after all, since their luminosity could be affected by the age of their parent stars.

If dark energy density is not constant in time, it flips conventional cosmological wisdom on its head, forcing scientists to look afresh at a universe that may be decelerating, and perhaps eventually contracting before collapsing in on itself in a ‘Big Crunch’.

The study has already set off a fierce debate amongst cosmologists, with many doubting if there is enough evidence to revamp the LCDM any time soon, or if at all.

For instance, in an email to the author, University of Michigan cosmologist Dragan Huterer expressed doubts about dark energy evolving with time. “But this is really hard to evaluate as we do not have any compelling theoretical models for dark energy. So, from a theoretical point of view, it is not clear,” Prof. Huterer added. ”From the observational/experimental point of view, the statistical significance of the findings is strong, but not sufficiently strong to claim a discovery. We need to collect and analyse more data to be sure.”

Brian Schmidt, distinguished professor of astronomy at the Australian National University and one of the three astrophysicists who won the Nobel Prize for their work on dark energy, is sceptical about the study’s consequences for the LCDM.

“If validated, these findings would not negate the (standard) model of the cosmos, but would modify it,” Prof. Schmidt wrote in an email. “Basically, instead of a constant [cosmological constant], we would have something that evolves over time.”

He said he doesn’t think that this would give rise to whole new subfields of astrophysics either.

“If true, it will give theorists a new set of clues to understand dark energy. I think it would be contained in the current theoretical cosmology community — and not (in) a new subfield.”

Where is the jury?

Prof Huterer also said that “these developments would still continue in the realm of data-driven cosmology. And the fact that Type Ia supernovae have some new properties would inform the existing field of Type Ia supernovae astrophysics.”

Adam Riess, professor of physics and astronomy at the Johns Hopkins University who shared the 2011 Nobel Prize, also said the Yonsei University study doesn’t hold water.

“The study claims that Type Ia supernovae become systematically fainter with redshift because their progenitors evolve with cosmic time,” he said. “We show this is not supported by the data. Modern supernovae analyses already model and marginalise host-related systematics, like stellar mass and star-formation history, and when these are included, there is no significant evidence for luminosity evolution.”

According to Prof. Riess, “the study result arises from a very particular way of slicing the data and from assumptions that aren’t consistent with how supernova cosmology is done today.”

When the Dark Energy Survey 5 Year dataset sample is analysed with standard methods, he continued, “the allowed level of evolution is an order of magnitude smaller than what their model predicts. In short: their proposed effect isn’t seen in real data, and current analyses already guard against it.”

Wherein lies the rub then? According to Prof. Riess, the new study makes a leap from host galaxy age to supernova age that is not physically justified. This is something scientists have already tested and corrected for with much larger datasets.

“Present studies already correct for their claimed effect (age) because they correct for galaxy mass, and galaxy mass and age are directly correlated,” he said.

Taken together, the jury is out on the Yonsei University study. Cosmologists are currently looking to state-of-the-art instruments such as the Vera Rubin Observatory in Chile and NASA’s upcoming Nancy Grace Roman space telescope to throw light on dark energy’s role in the fate of the universe — whether it will eventually slow down and end in a Big Crunch or continue to expand until it fades away into virtual nothingness.

Prakash Chandra is a science writer.