Earth’s continents are not fixed. Over hundreds of millions of years, they drift, collide and reassemble, forming vast supercontinents that reshape the planet’s surface and atmosphere. These geological cycles unfold over timescales far beyond human history, but they leave enduring marks on climate, ocean circulation, and the survival of species.

The next of these transformations, scientists say, could carry profound consequences. Though it lies hundreds of millions of years ahead, the formation of Earth’s next supercontinent is expected to create unfamiliar environmental extremes, with deep implications for life as we know it.

A new peer-reviewed study published in Nature Geoscience, examines what such a world might look like. By combining advanced climate modelling with tectonic and atmospheric projections, researchers offer one of the most detailed forecasts to date of Earth’s long-term future. Their findings point to a scenario in which rising temperatures and declining habitability converge across most of the planet’s landmass.

A Warmer Planet, Reshaped by Land and Sun

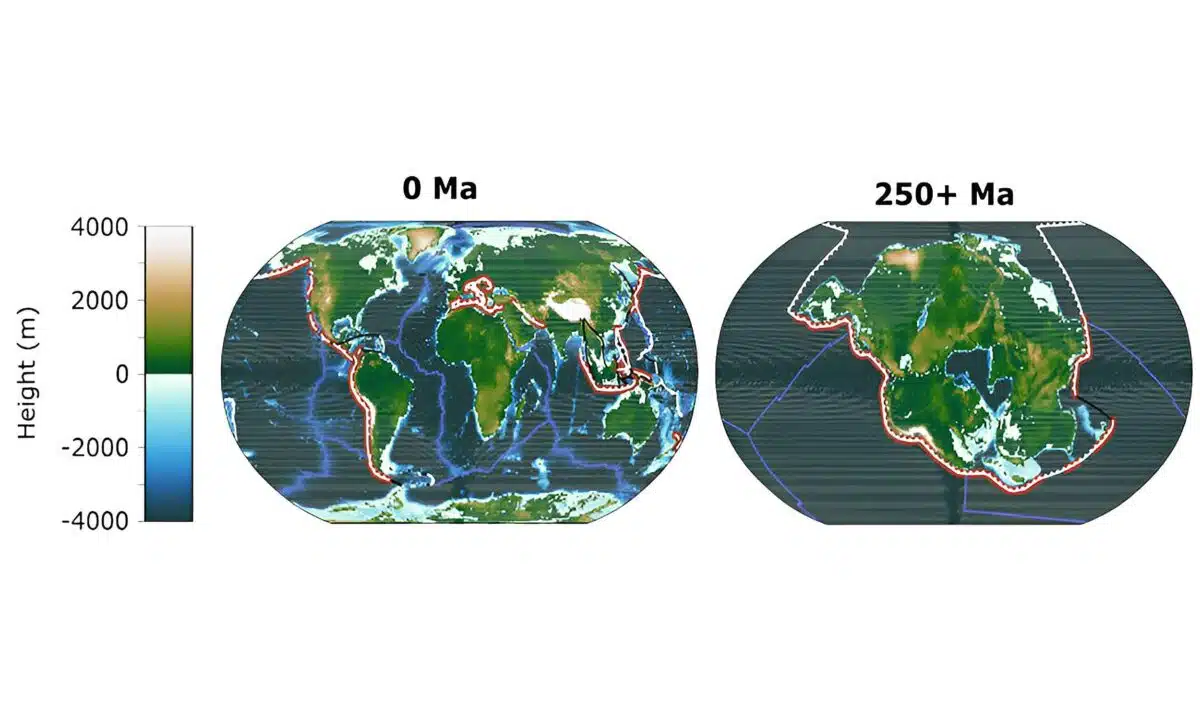

The central premise of the study is the formation of Pangea Ultima, a future supercontinent projected to emerge in approximately 250 million years. As Earth’s tectonic plates continue to shift, the continents are expected to converge into a single, massive landmass straddling the equator.

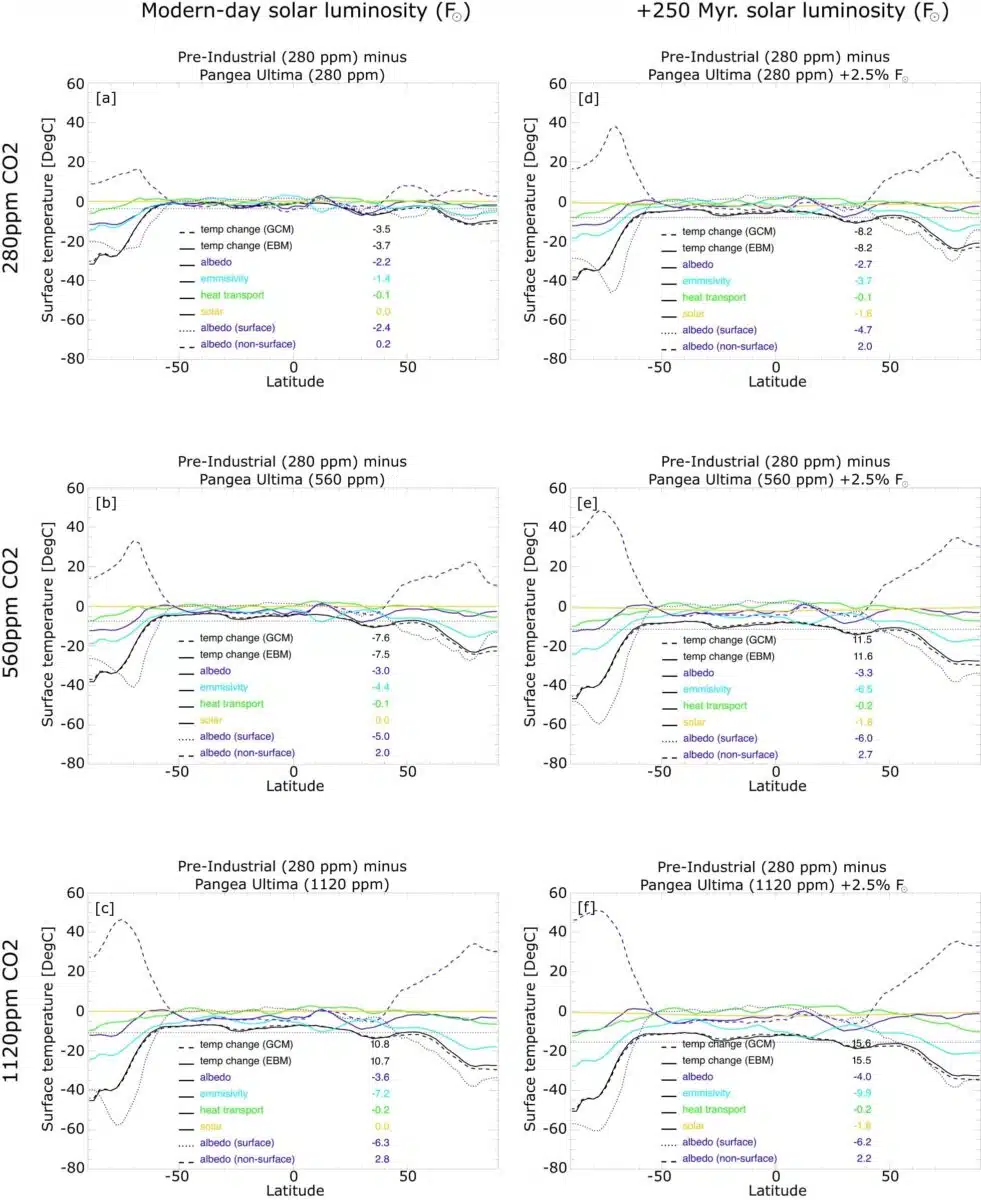

This configuration would alter the planet’s energy balance in fundamental ways. With less ocean surface to moderate heat and more land concentrated in the tropics, global temperatures would rise sharply. The study’s authors modelled these conditions using the HadCM3L general circulation model, incorporating a 2.5 percent increase in solar radiation, consistent with astrophysical estimates for that timeframe.

Illustration showing the geography of today’s Earth and the projected geography of Earth in 250 million years, when all the continents converge into one supercontinent (Pangea Ultima). Credit: University of Bristol

Illustration showing the geography of today’s Earth and the projected geography of Earth in 250 million years, when all the continents converge into one supercontinent (Pangea Ultima). Credit: University of Bristol

The simulations show global mean land temperatures increasing by as much as 30 degrees Celsius compared to pre-industrial levels. Average temperatures across the future supercontinent would reach between 24.5°C and 35.1°C, with regional highs climbing significantly further.

These projected values exceed the physiological limits of many mammals. Researchers identify three key factors driving this outcome: the continentality effect, increased solar luminosity, and high concentrations of atmospheric carbon dioxide (CO₂), which are expected to rise due to intensified volcanic activity during continental convergence.

Critical Heat Stress and Declining Habitability

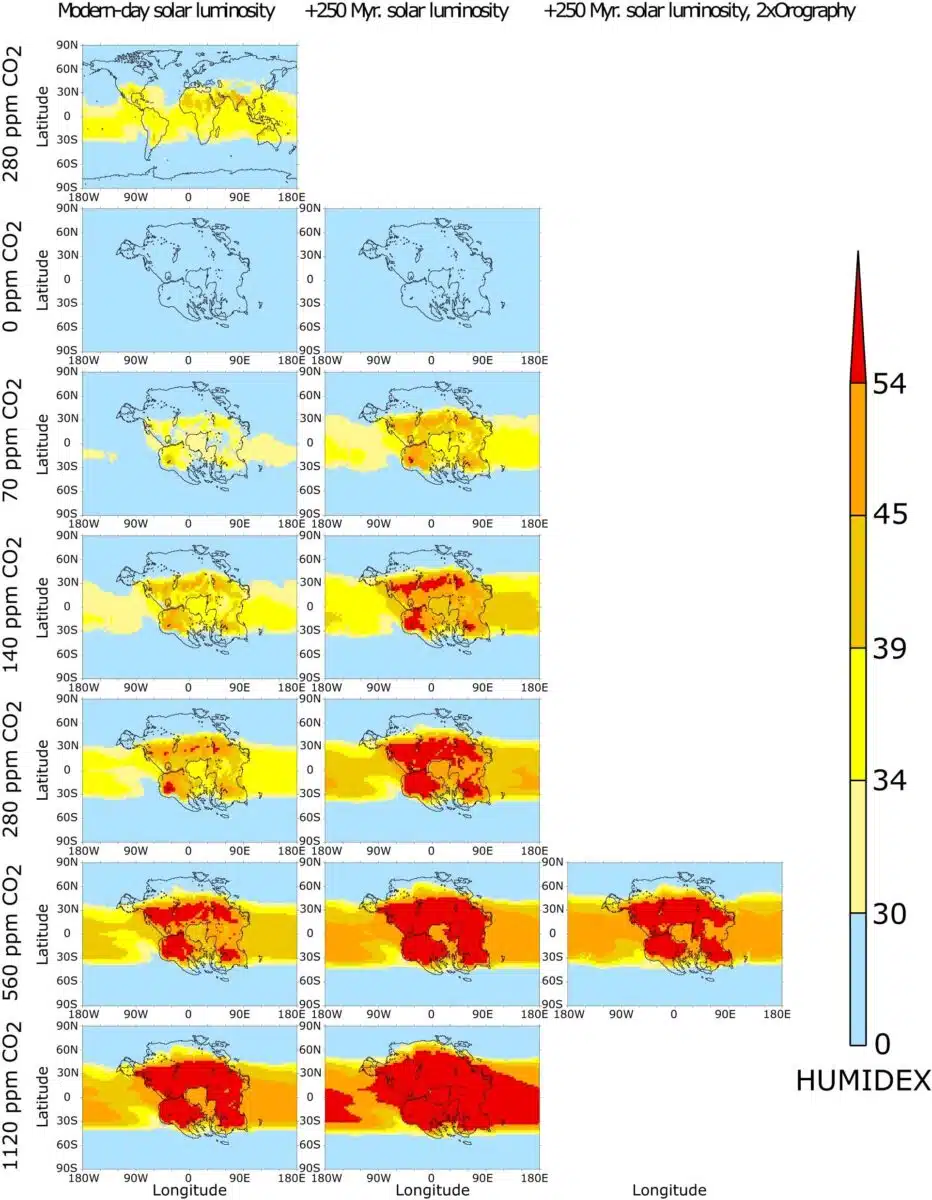

One of the study’s most notable findings relates to heat stress thresholds. Mammals regulate body temperature through evaporative cooling, such as sweating or panting, but this mechanism fails when heat and humidity surpass a certain limit. The researchers use indicators such as wet-bulb temperature and the Humidex index to estimate survivability across various regions.

Wet-bulb temperatures over 35°C, the limit at which humans can no longer cool themselves effectively, are projected to occur widely. Humidex values—used to assess the combined impact of temperature and humidity—also exceed levels deemed dangerous. Even under mid-range CO₂ scenarios (560 ppm), only 16 percent of the supercontinent’s land area would remain within habitable thresholds. At higher CO₂ levels (1,120 ppm), that share drops to just 8 percent.

Warmest month HUMIDEX for each experiment at present day (column 1), +2.5% present day solar luminosity (column 2) and +2.5% present day solar luminosity with a doubling of the topography (column 3) at 0 pm, 70 pm, 140 pm, 560 pm and 1120 ppm CO2. Credit: Nature Geoscience

Warmest month HUMIDEX for each experiment at present day (column 1), +2.5% present day solar luminosity (column 2) and +2.5% present day solar luminosity with a doubling of the topography (column 3) at 0 pm, 70 pm, 140 pm, 560 pm and 1120 ppm CO2. Credit: Nature Geoscience

“Widespread temperatures of between 40 to 50° Celsius (104 to 122° Fahrenheit), and even greater daily extremes, compounded by high levels of humidity, would ultimately seal our fate,” said Dr Alexander Farnsworth, lead author and senior research associate at the University of Bristol, which coordinated the modelling.

In addition to direct heat stress, aridity would reduce access to water and vegetation, limiting food availability. These factors, when combined, would place extreme physiological pressure on mammals, including humans. Migration across vast desert interiors would become increasingly difficult, while high-latitude refuges would offer only limited relief.

Volcanism, Carbon Feedbacks, and Extinction Risk

Past extinction events have often followed sharp increases in atmospheric CO₂. The researchers modelled long-term carbon levels using the SCION biogeochemical framework, factoring in tectonic plate movements, volcanic outgassing and changes in continental weathering.

The study estimates future background CO₂ levels to range between 410 and 816 ppm, with a mean value of 621 ppm. These levels would produce a sustained greenhouse climate even without additional anthropogenic input. The reduced effectiveness of silicate weathering—a natural CO₂ sink—on a dry supercontinent would further slow the removal of excess carbon from the atmosphere.

Energy balance model analysis for each experiment relative to the 280 ppm Pangea Ultima experiment. Credit: Nature Geoscience

Energy balance model analysis for each experiment relative to the 280 ppm Pangea Ultima experiment. Credit: Nature Geoscience

Historical records provide relevant comparisons. The end-Permian extinction, approximately 252 million years ago, saw a temperature spike of roughly 10°C and the loss of more than 90 percent of marine species. Similar carbon and temperature dynamics are projected for the Pangea Ultima period, with terrestrial conditions likely to exceed those past thresholds.

As noted in the Earth.com report on the study, “with so much territory turning arid, the quest for food and hydration would become daunting.” Even species with adaptive strategies such as hibernation or burrowing would face mounting pressure, particularly as vegetation loss undermines ecosystems across latitudes.

Habitability Beyond Earth and Time

The findings also carry implications for the study of exoplanets. Traditionally, planetary habitability is assessed using orbital distance from a star. Earth’s own trajectory shows that habitability is not fixed; it can vary based on internal dynamics such as continental layout and atmospheric chemistry.

“This work also highlights that a world within the so-called ‘habitable zone’ of a solar system may not be the most hospitable for humans depending on whether the continents are dispersed, as we have today, or in one large supercontinent,” Farnsworth said, as quoted in Nature Geoscience.

Under high-CO₂ and increased solar conditions, Earth itself would no longer meet the criteria of widely used astrophysical indices, such as the Earth Similarity Index (ESI), which considers mass, radius, temperature, and capacity to support liquid water. The researchers found that all projected Pangea Ultima scenarios fail to meet the ESI’s habitability threshold of 0.8, despite the planet remaining within its current orbital zone.