It’s late afternoon when the boys show up for their after-school programs at Hope Farm, a nearly 30-year-old Fort Worth nonprofit that aims to break the cycle of poverty and crime among boys who don’t have father figures.

There’s a stranger being shown around on the south Fort Worth campus, and the boys know what to do about it: line up, cheerfully introduce themselves, make eye contact and extend their hands for a shake. “Who are you?” one says, politely.

Those sorts of manners and confidence are just a part of the Hope Farm equation.

“We tackle ending the cycle of fatherlessness. We’re ending generational cycles of poverty,” said Sacher Dawson, the nonprofit’s executive director since 2018. “We’re ending generational cycles of hopelessness where they find new hope. We’re shining that light in places and in people that I think a lot of the area forgets about.”

Hope Farm runs afterschool programs at its two campuses in Fort Worth and one in Dallas through Bible study, reading labs, and homework tutoring. Boys come to the program by buses from school and being dropped off by moms and guardians. (Maria Crane | Fort Worth Report/CatchLight Local/Report for America)

Hope Farm runs afterschool programs at its two campuses in Fort Worth and one in Dallas through Bible study, reading labs, and homework tutoring. Boys come to the program by buses from school and being dropped off by moms and guardians. (Maria Crane | Fort Worth Report/CatchLight Local/Report for America)

Hope Farm, which has another campus in west Fort Worth’s Como neighborhood and one in south Dallas, is pushing ahead with a $4 million fundraising campaign that the nonprofit leaders plan to lead to the establishment of an elementary school.

In the fall, the nonprofit neared completion of a vocational building at its main campus in south Fort Worth. Dawson called the training building a major step up.

“We pound into (the boys) go to college, go to college, go to college, but we realized not all of our boys are going to college,” Dawson said.

Construction on the Slone Vocational Center — named after longtime Hope Farm supporter and former board member Tom Slone — is about 95% complete, Dawson said. The five high-demand trades Hope Farm will focus on are: welding, auto mechanics, information technology, culinary and plumbing.

“They can earn you a very good living if taken seriously,” Dawson said.

Hope Farm also needs to make repairs to the gymnasium and renovate and expand it. The building is critical to all of the organization’s programs: Bible study, literacy, homework and tutoring, choir, recreation and, every day at 5:30 p.m., service of a freshly prepared dinner. Hope Farm wants to create HOPE Farm Academy, a kindergarten through fifth grade school, in the renovated gym.

Hope Farm also needs new vehicles, which it uses to pick up boys at their schools each afternoon, officials said.

Hope Farm is at the end of the first year of a four-year campaign to raise $4 million:

- $2.5 million to the gym repairs and renovation

- $1 million to the academy

- $500,000 for the vocational center

- $200,000 for vehicles

So far, Hope Farm has raised about $300,000 toward the goal, Dawson said.

“We feel that’s very doable,” Dawson said.

Hope Farm is finishing the construction of a vocational center on their Fort Worth campus on Dec. 10, 2025. Hope Farm will host its trainings for culinary, plumbing, IT, auto and welding programs once completed. (Maria Crane | Fort Worth Report/CatchLight Local/Report for America)

Hope Farm is finishing the construction of a vocational center on their Fort Worth campus on Dec. 10, 2025. Hope Farm will host its trainings for culinary, plumbing, IT, auto and welding programs once completed. (Maria Crane | Fort Worth Report/CatchLight Local/Report for America)

All of this is a long way from 1997, when longtime former police officers Gary Randle and Noble Crawford opened Hope Farm in one building of what’s now the south Fort Worth campus in the Evans Avenue corridor off Interstate 35W. The first group served consisted of 12 boys.

That campus now takes up a city block with several buildings and is Hope Farm’s largest, this year serving 60 boys. The Como campus serves 15, while the Dallas site serves 33. Randle retired after 20 years, and Crawford died in 2024.

Hope Farm brings in boys who are 5 to10 years old and don’t have a father figure at home. Dawson said 98% of the boys are Black, and almost all are low-income.

Hope Farm wants its boys to remain through high school, and some staff are dedicated to helping them figure out what’s next after graduation.

This year, three high school seniors will graduate after having been with Hope Farm since elementary school, Dawson said. Alumni who graduate get their framed pictures displayed on a wall at Hope Farm. Rebecca Leppert, Hope Farm’s development director, said 100% of its students stick with the program through graduation.

Shamar Peoples volunteers at Hope Farm and spends time with the boys in the program. Peoples went through the Hope Farm program as a young boy and now works as a police officer. (Maria Crane | Fort Worth Report/CatchLight Local/Report for America)

Shamar Peoples volunteers at Hope Farm and spends time with the boys in the program. Peoples went through the Hope Farm program as a young boy and now works as a police officer. (Maria Crane | Fort Worth Report/CatchLight Local/Report for America)

Shamar Peoples was a student who stayed with Hope Farm through his graduation. Peoples, now 23 and a patrol officer for the Arlington police department, was raised by his grandparents after his parents died young.

At 11, his grandmother asked friends at church if they knew of any programs for him.

“They took a chance on me,” said Peoples, who now volunteers with the children at Hope Farm.

Peoples said he was struggling in school at the time, and the nonprofit’s connections helped him get into a private school with sponsorship. He later earned an associate degree in criminal justice at Tarrant County College, setting a foundation for his future as a police officer.

Hope Farm’s teaching of ethics and consequences for behavior forms the backbone for the group’s success, he said. The boys maintain accountability logs and review those regularly with their Hope Farm mentors. During a recent Wednesday, a student was helping rake up leaves as a consequence for what he told his mentors was an “incident at school.”

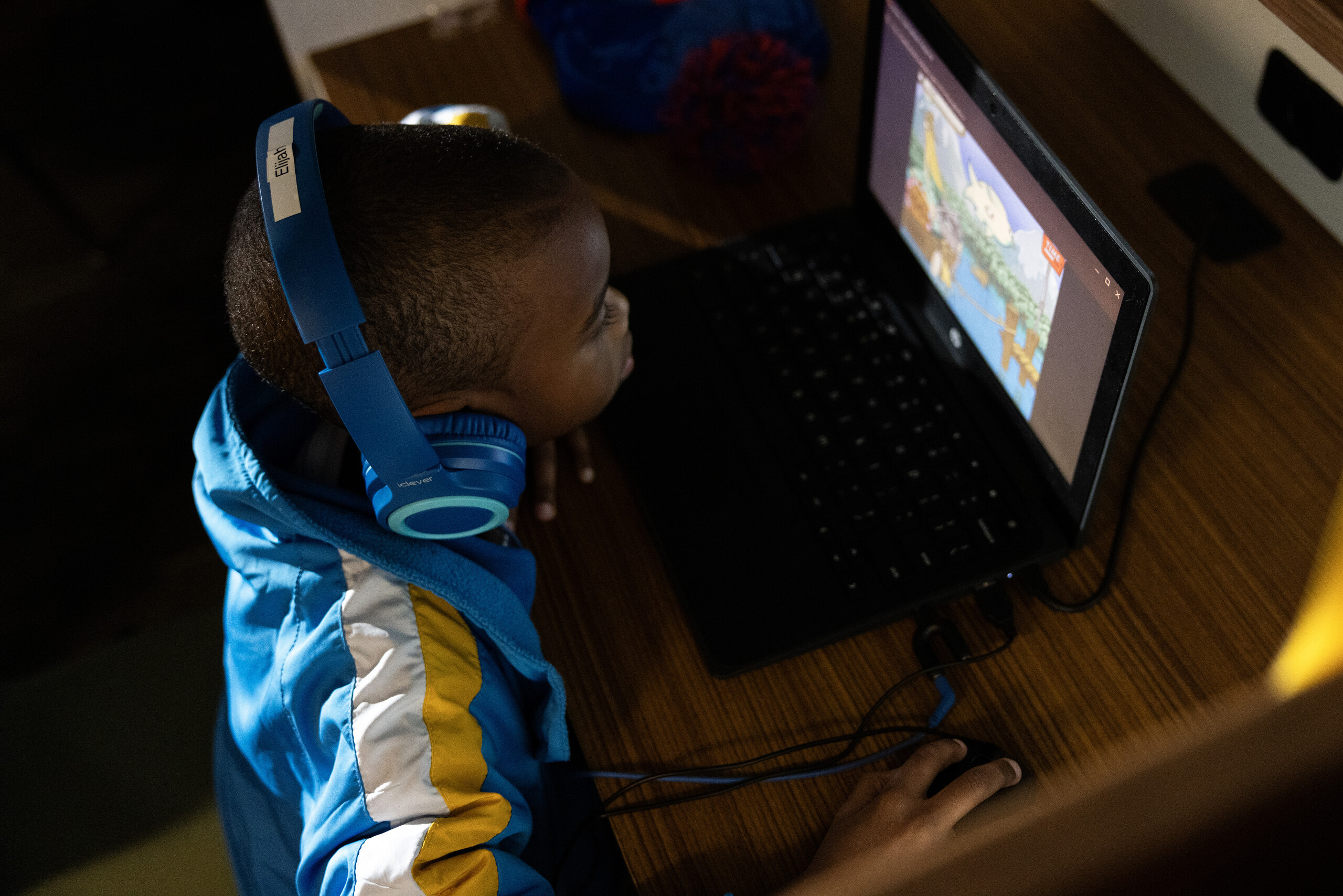

Elijah works on his reading labs at Hope Farm in Fort Worth on Dec. 10, 2025. The boys go to the reading lab a few times each week to work on their skills. Volunteers help the boys when needed. (Maria Crane | Fort Worth Report/CatchLight Local/Report for America)

Elijah works on his reading labs at Hope Farm in Fort Worth on Dec. 10, 2025. The boys go to the reading lab a few times each week to work on their skills. Volunteers help the boys when needed. (Maria Crane | Fort Worth Report/CatchLight Local/Report for America)

LaDarian Bickems, a mentor at Hope Farm, completes Bible study with the boys on Dec. 10. The boys talked about the Ten Commandments, and Bickers led them through discussions. (Maria Crane | Fort Worth Report/CatchLight Local/Report for America)

LaDarian Bickems, a mentor at Hope Farm, completes Bible study with the boys on Dec. 10. The boys talked about the Ten Commandments, and Bickers led them through discussions. (Maria Crane | Fort Worth Report/CatchLight Local/Report for America)

The boys arrive on the campus weekdays after school and run rotations in different programs before finishing with dinner. The elementary school choir in December sang the national anthem at a Dallas Mavericks home game.

“All of that kind of builds you up,” Peoples said.

Arthur Breland is another Hope Farm alum. He was born and reared in Morningside, went on to graduate from a Bible college in Ohio and now is a church pastor in Atlanta.

Breland was 8 when his father went to prison. Breland’s mother held multiple jobs but usually wasn’t home when he arrived home from school, he said.

“I was a latchkey kid,” he said. “I was responsible for getting myself home and feeding myself. A lot of my friends, we all pretty much walked ourselves to school and walked home from school, and our parents were working or absent.”

He learned about Hope Farm in second grade and told his mother.

“We rode around the south side of Fort Worth for about 20 minutes looking for Hope Farm,” he said. “It was just a small white house with a red door. Nothing like it is now.”

Part of Hope Farm’s mission is to introduce its students to a relationship with Christ.

“My mother also developed a relationship with Christ,” Breland said.

Ashtyn prepares to sing the National Anthem with peers from the Hope Farm on Dec. 10, 2025. The boys were preparing to sing at the Mavericks game that Friday. (Maria Crane | Fort Worth Report/CatchLight Local/Report for America)

Ashtyn prepares to sing the National Anthem with peers from the Hope Farm on Dec. 10, 2025. The boys were preparing to sing at the Mavericks game that Friday. (Maria Crane | Fort Worth Report/CatchLight Local/Report for America)

That turned into the development of his calling to go into the ministry, he said. Hope Farm connections also helped him transfer into Arlington Heights High School, where he participated in its arts programs.

“I was not the best student,” he said. “But when I really got serious about my relationship with Christ, I was able to focus.”

Hope Farm recruits through word-of-mouth, relationships with school administrators and counselors, PTAs and school open houses, and community events.

Word-of-mouth is critical, with Hope Farm also providing significant programming to its boys’ moms, such as free Wi-Fi, access to computers, cooking classes and opportunities for community with other mothers.

“My boys’ life would look a lot different if they didn’t have Hope Farm,” Lonnetta Wilson, whose two sons — one a high school junior and the other a sixth grader — are enrolled in Hope Farm.

Wilson, a social worker employed by Tarrant County, is a single mom by divorce.

Her sons’ male role models have all been at Hope Farm, she said.

The nonprofit has helped the boys with everything from leadership to practical skills to insight into opportunities following high school. Her oldest son is interested in dentistry and, through Hope Farm’s network, has already completed internships with a dentist, she said.

If a family is going through a tough strait, “somebody’s going to show up” to offer help, she said of the nonprofit’s reach.

Boys at the Hope Farm play various sports with one another on Dec. 10, 2025. One of the three rotations the boys do at the Hope Farm includes recreational time to play sports such as basketball. (Maria Crane | Fort Worth Report/CatchLight Local/Report for America)

Boys at the Hope Farm play various sports with one another on Dec. 10, 2025. One of the three rotations the boys do at the Hope Farm includes recreational time to play sports such as basketball. (Maria Crane | Fort Worth Report/CatchLight Local/Report for America)

D’Ante and his peers head upstairs to the choir room at the Hope Farm on Dec. 10, 2025. (Maria Crane | Fort Worth Report/CatchLight Local/Report for America)

D’Ante and his peers head upstairs to the choir room at the Hope Farm on Dec. 10, 2025. (Maria Crane | Fort Worth Report/CatchLight Local/Report for America)

To deepen the moms’ ties to Hope Farm, the group started Parent University in 2014 to provide parenting, spiritual and professional development tips.

“This holistic approach has been great,” Dawson said. “What we’ve seen since (Parent University’s launch) is that our retention numbers have almost doubled; the kids can’t go home now and tell the mom the program stinks.”

Allisha Prescott is another of Hope Farm’s moms. Her 10-year-old son has been with the nonprofit since he was 6. Prescott sought out Hope Farm in seeking help for her son to move beyond behavior problems.

“At one point, I thought I was going to have to put my child on medication,” she said.

At the start of the interview process, Hope Farm staff “prayed with me,” she said.

Today, she says of her son: “He has learned about the love of Jesus. I don’t have to ask him to do his homework anymore. His behavior has improved dramatically. They really, really make these children feel seen.”

Scott Nishimura is a senior editor at the Fort Worth Report. Contact him at scott.nishimura@fortworthreport.org.News decisions are made independently of our board members and financial supporters. Read more about our editorial independence policy here.

This <a target=”_blank” href=”https://fortworthreport.org/2026/01/01/hope-farm-launches-4m-push-to-expand-north-texas-job-training-add-school/”>article</a> first appeared on <a target=”_blank” href=”https://fortworthreport.org”>Fort Worth Report</a> and is republished here under a <a target=”_blank” href=”https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nd/4.0/”>Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License</a>.<img src=”https://i0.wp.com/fortworthreport.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/cropped-favicon.png?resize=150%2C150&quality=80&ssl=1″ style=”width:1em;height:1em;margin-left:10px;”>

<img id=”republication-tracker-tool-source” src=”https://fortworthreport.org/?republication-pixel=true&post=338866&ga4=2820184429″ style=”width:1px;height:1px;”><script> PARSELY = { autotrack: false, onload: function() { PARSELY.beacon.trackPageView({ url: “https://fortworthreport.org/2026/01/01/hope-farm-launches-4m-push-to-expand-north-texas-job-training-add-school/”, urlref: window.location.href }); } } </script> <script id=”parsely-cfg” src=”//cdn.parsely.com/keys/fortworthreport.org/p.js”></script>