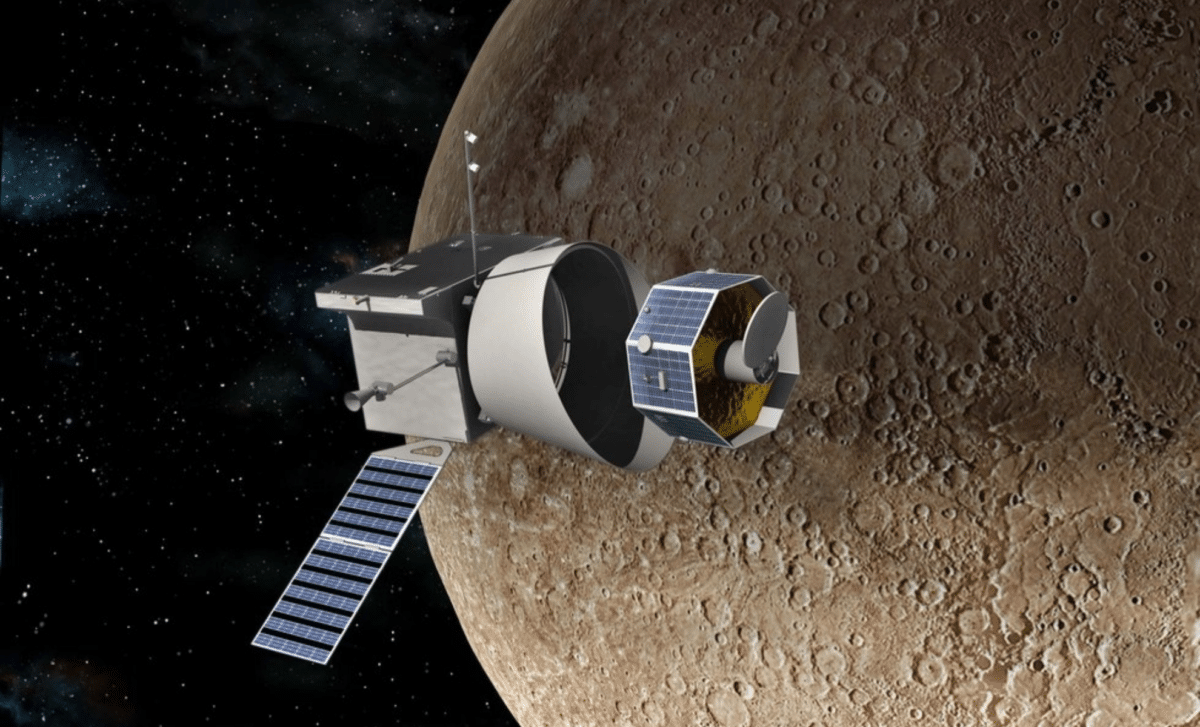

The long-anticipated BepiColombo mission is entering its decisive phase. Launched in 2018, this joint endeavor between the European Space Agency (ESA) and Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA) is finally expected to enter Mercury’s orbit in the second half of 2026. The spacecraft, composed of two orbiters, MPO (Mercury Planetary Orbiter) and Mio (Mercury Magnetospheric Orbiter), will begin collecting rich scientific data that could reshape our understanding of the innermost planet in the solar system.

Why Mercury Still Holds Major Mysteries

Despite its proximity to Earth, Mercury remains one of the least understood terrestrial planets. Its extreme temperatures, eccentric orbit, and magnetic anomalies have long puzzled astronomers. Unlike Mars or Venus, Mercury’s thin atmosphere, iron-rich core, and chaotic magnetic field defy easy classification. Understanding Mercury may reveal not just its own history, but broader insights into planetary evolution and solar system formation.

The complexity of Mercury’s gravitational field made reaching stable orbit a serious challenge. BepiColombo’s strategy, six flybys using Mercury’s own gravity to decelerate, was inspired by Italian mathematician Giuseppe “Bepi” Colombo, after whom the mission is named. These flybys have gradually adjusted the spacecraft’s trajectory, preparing it for insertion into orbit without burning excessive fuel.

Once in orbit, the real work begins. “It will be taking the first X-ray images of a surface of another planetary body,” says Charly Feldman at the University of Leicester, who helped develop one of the MPO’s instruments. This data could help identify surface elements and mineral compositions with unprecedented resolution, opening the door to comparisons with Earth, Mars, and the Moon.

Instruments, Expectations, And High Stakes

According to New Scientist, BepiColombo carries an array of high-tech instruments across both orbiters. The MPO, managed by ESA, focuses on surface and internal structure, while JAXA’s Mio will study Mercury’s magnetic field and exosphere. Each orbiter is optimized for its scientific goals, but they must function autonomously after deployment, there’s no second chance once they’re released.

“There’s that anticipation of, is our instrument still working and is it going to work as we expect?” Feldman admits. “There’s nothing we can do if it’s broken. It’s been building for a very long time, so whilst it is incredibly exciting, it’s also a little bit nerve-wracking.”

This comment reflects a broader anxiety among scientists. The instruments were built nearly a decade ago, tested under extreme simulations, and launched into the harshness of space. The risk is real, but so is the reward. If successful, BepiColombo will help solve long-standing questions, including the origin of Mercury’s magnetic field, the reason behind its high density, and how its surface evolved under such extreme conditions.

Broader Impact On Planetary Science

The significance of BepiColombo isn’t limited to Mercury. As Feldman puts it, “If you can understand how the different planets have come to be as they are, you can understand the dynamics of the whole solar system.” The mission’s findings could recalibrate models of planetary formation, especially for rocky bodies close to their host stars, a scenario increasingly seen in exoplanetary research.

New Scientist emphasizes that this marks a critical moment not only for ESA and JAXA but for the entire scientific community. With data arriving from both surface imaging and magnetic field mapping, the mission is expected to generate years of follow-up research. It may also influence future missions, both robotic and crewed, by providing fresh perspectives on planetary geology and solar interactions.