There is no shortage of interest in Titan, Saturn’s largest moon. Its dense, nitrogen-rich atmosphere, surface lakes and seas, and cycles that mirror Earth’s in eerie, hydrocarbon-based forms have drawn attention for decades. Even with no direct missions planned for its oceanic north just yet, the moon continues to stand out as one of the most Earth-like places in the solar system.

Among Titan’s most studied features is Kraken Mare, a vast sea sprawling across the upper latitudes. It has often been described in comparisons: larger than all five Great Lakes combined, more massive than any other extraterrestrial liquid body ever detected. Its sheer scale warrants attention, but until recently, the specifics of its depth remained uncertain.

Earlier measurements suggested the sea wasn’t particularly deep. Just enough to matter. But newly reprocessed data from NASA’s Cassini mission has shifted that view. A study published in the Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets revealed that parts of Kraken Mare may reach depths of up to 300 metres, far deeper than prior estimates.

Revised Data From Cassini Alters Depth Estimates

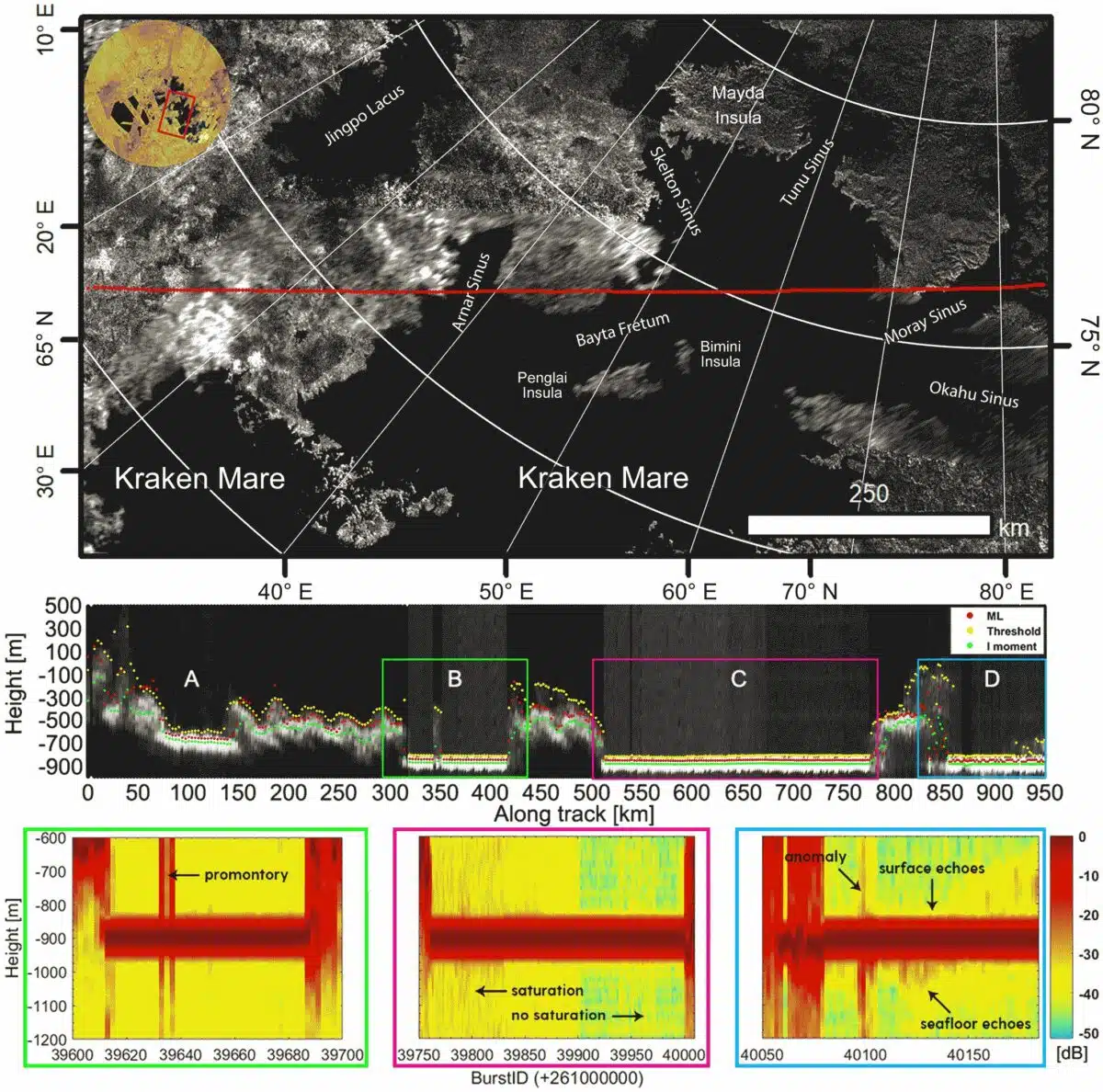

The updated findings are based on data collected during Cassini’s 104th flyby of Titan on 21 August 2014. During that pass, the spacecraft’s radar instrument scanned a 200-kilometre track across the eastern edge of Kraken Mare. In a 40-kilometre stretch, the radar produced a distinct double echo — one from the sea’s surface and one from its bottom.

Details of this analysis are explained in NASA’s own article, Plumbing Coastal Depths in Titan’s Kraken Mare, where the agency described how radar reflections returned depth estimates ranging from 20 to 35 metres in the shallower region. But in other parts of the transect, the radar signal never returned from the bottom, indicating significant absorption by the sea’s contents.

Radar data from NASA’s Cassini spacecraft reveal the depth of liquid methane/ethane seas on Saturn’s moon Titan. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/ASI/Cornell

Radar data from NASA’s Cassini spacecraft reveal the depth of liquid methane/ethane seas on Saturn’s moon Titan. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/ASI/Cornell

From this, researchers inferred that the sea’s central regions could reach depths of 300 metres, making Kraken Mare not only the deepest known sea on Titan, but one of the most substantial surface reservoirs in the outer solar system.

According to the study, Kraken Mare holds roughly 80 percent of Titan’s surface liquids, confirming its central role in the moon’s surface hydrology.

The Methane–Ethane Cycle at Titan’s Surface

On Titan, methane serves as water does on Earth — evaporating into clouds, falling as rain, and flowing into lakes and seas. Alongside it is ethane, another hydrocarbon that forms as methane breaks down under solar radiation. These compounds remain liquid due to Titan’s average surface temperature of about minus 179 degrees Celsius.

Research suggests that Kraken Mare’s composition may be richer in ethane than previously assumed. The study’s authors attribute this to the sea’s latitude and size, which likely result in lower methane replenishment from rainfall or runoff compared with smaller polar lakes.

SAR mosaic of the northern region of Kraken Mare with the T104 fly-by altimetry ground track in red: the map is in Polar Stereographic projection with the North Pole approximately toward the upper right (above). Altimetry profile with highlighted positions of the three sections where the footprint intercepted the liquid surface of Kraken Mare. The central and upper panels have the same horizontal coordinate (center). Credit: Nature Geoscience

SAR mosaic of the northern region of Kraken Mare with the T104 fly-by altimetry ground track in red: the map is in Polar Stereographic projection with the North Pole approximately toward the upper right (above). Altimetry profile with highlighted positions of the three sections where the footprint intercepted the liquid surface of Kraken Mare. The central and upper panels have the same horizontal coordinate (center). Credit: Nature Geoscience

This hypothesis is supported by surface observations collected earlier by Cassini and its companion probe Huygens, which in 2005 confirmed that methane rain reaches the surface of the moon.

Because ethane absorbs radar energy more efficiently than methane, the change in composition may partly explain why radar signals failed to return from deeper regions of Kraken Mare. The characteristics of these liquids not only affect remote sensing performance, but also reflect broader geophysical processes shaping Titan’s surface.

Exploration Challenges and Mission Prospects

Despite the success of Cassini’s radar system, there are limits to what can be observed remotely. Its Synthetic Aperture Radar was optimised to penetrate Titan’s dense haze and map its surface, but the ability to detect undersea topography was dependent on liquid transparency and incident angles.

Where radar echoes were lost, researchers estimated depth based on signal attenuation — essentially, how much energy the liquid absorbed. While this provides valuable insights, it remains an indirect method. Direct exploration will be required to fully understand the physical and chemical structure of Kraken Mare.

An artist’s impression of Ligeia Mare, at Titan’s north pole. Credit: University of Paris/IPGP/CNRS/A. Lucas

An artist’s impression of Ligeia Mare, at Titan’s north pole. Credit: University of Paris/IPGP/CNRS/A. Lucas

NASA has studied a conceptual Titan submarine mission since 2015. The proposed vehicle would explore Kraken Mare autonomously, using instruments to analyse pressure, temperature, currents, and hydrocarbon composition. Although not currently funded, the mission concept remains under consideration and could inform future exploration architecture.

The Dragonfly mission, launching in 2027, will land near Titan’s equator and explore sand dunes, not seas. Still, it will deliver critical data on surface chemistry, weather, and atmospheric conditions, helping researchers build a fuller picture of Titan’s environment and support planning for subsequent missions to its lakes and seas.

A Deeper Sea, and More Unknowns

The realisation that Kraken Mare is significantly deeper than once thought reshapes assumptions about Titan’s surface and climate. A sea of this scale, capable of storing vast quantities of hydrocarbons, prompts new questions about the moon’s geologic activity, cryovolcanism, and long-term methane balance.

These findings also reinforce the lasting value of Cassini-Huygens data, which continue to yield discoveries years after the mission concluded in 2017. Reanalysing archived radar tracks and refining interpretation methods has proven essential to understanding one of the most Earth-like moons in the solar system.

Titan’s liquid hydrocarbon seas remain among the most compelling exploration targets in the outer solar system. Kraken Mare, with its exceptional scale and complexity, will likely play a central role in future efforts to understand surface–atmosphere interactions, planetary chemistry, and the potential for exotic forms of habitability beyond Earth.