The research, led by a team at Rice University, suggests that ancient Martian lakes did not require a warm climate to persist. Instead, a thin ice cover may have slowed evaporation and heat loss, allowing water to remain liquid through seasonal cycles. This model offers a new explanation for the preserved lake beds and sediment layers observed by rovers on the Martian surface.

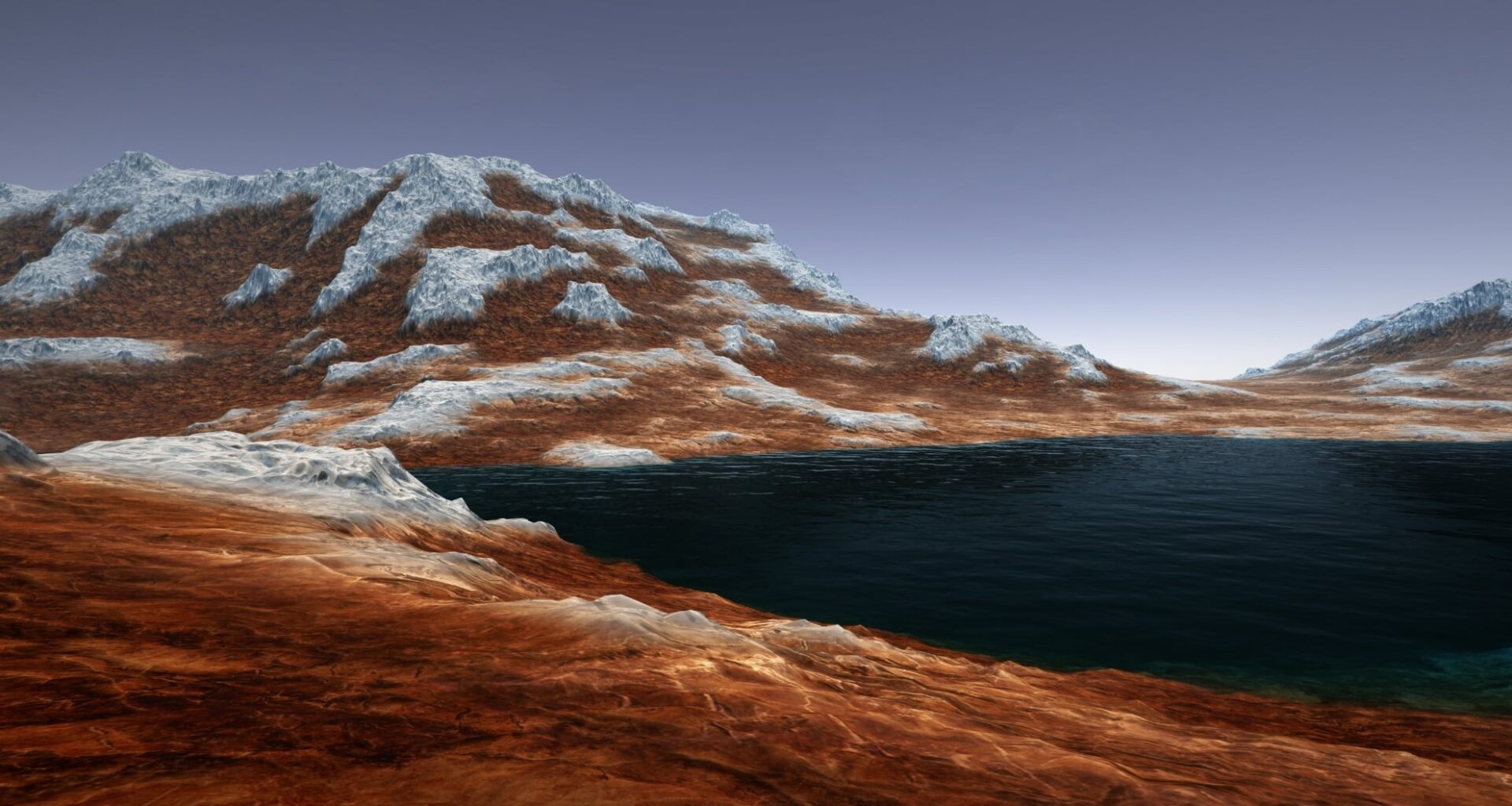

Mars today is dry and frozen, but its surface preserves clear evidence of a wetter past: wide lake basins, channels shaped by flowing water, and sediments deposited in quiet, stable conditions. Climate models, however, have long struggled to explain how liquid water could have lasted under the cold and thin atmosphere that likely existed on early Mars.

Short-term warming from impacts or volcanic activity could not account for the well-formed, long-lived lake features visible today. The new study provides an alternative explanation that does not rely on brief, dramatic climate shifts.

Thin Ice Cover as a Protective Layer

The model proposed by the researchers shows that seasonal ice, rather than thick permanent ice, could have protected lakes from freezing entirely. “Seeing ancient lake basins on Mars without clear evidence of thick, long-lasting ice made me question whether those lakes could have held water for more than a single season in a cold climate,” said Eleanor Moreland, the study’s lead author and a graduate student at Rice University.

According to the study, the ice would have formed during colder seasons, reducing heat loss and evaporation, and melted during warmer periods, allowing sunlight to warm the water. This cycle could have kept lakes stable for years. “Because the ice is thin and temporary, it would leave little evidence behind,” said Professor Kirsten Siebach, a co-author, explaining why rovers have not found clear traces of thick, glacial ice in these basins, reports Earth.com.

Adapting Climate Models for Mars

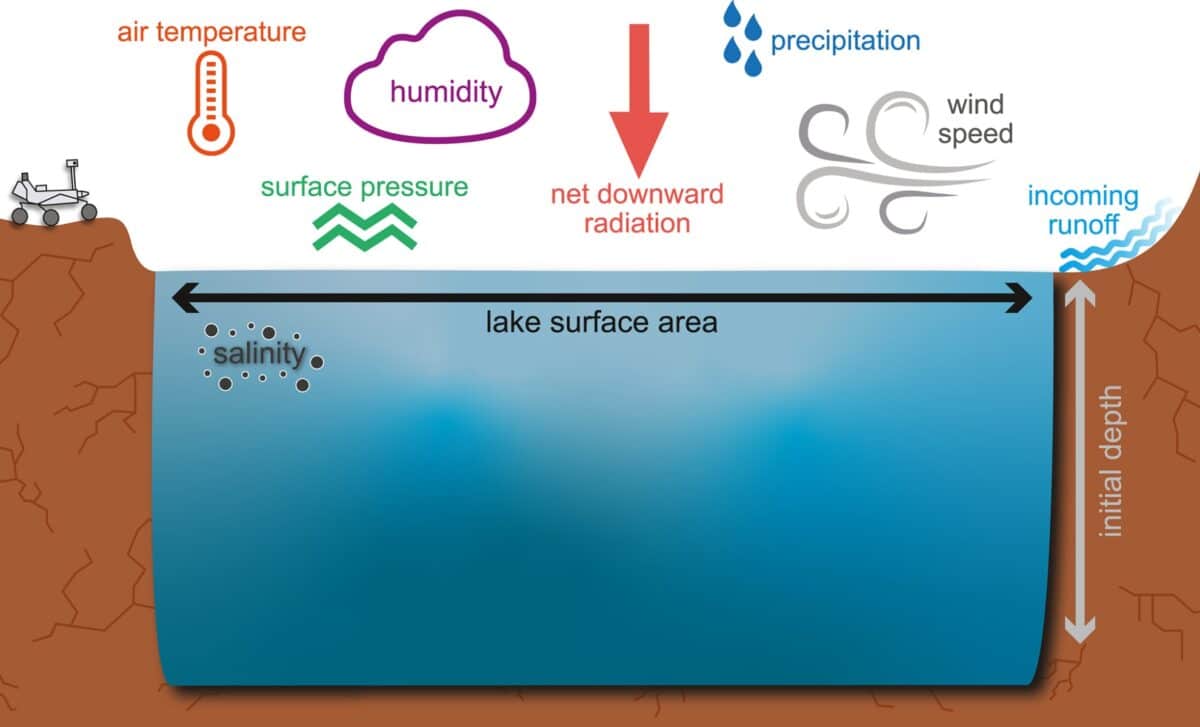

To explore their hypothesis, the research team used Proxy System Modeling, a tool initially developed to reconstruct ancient Earth climates using indirect records like tree rings and ice cores. Since Mars lacks such records, the team used minerals, rock layers, and chemical data collected by rovers as stand-ins for past climate indicators.

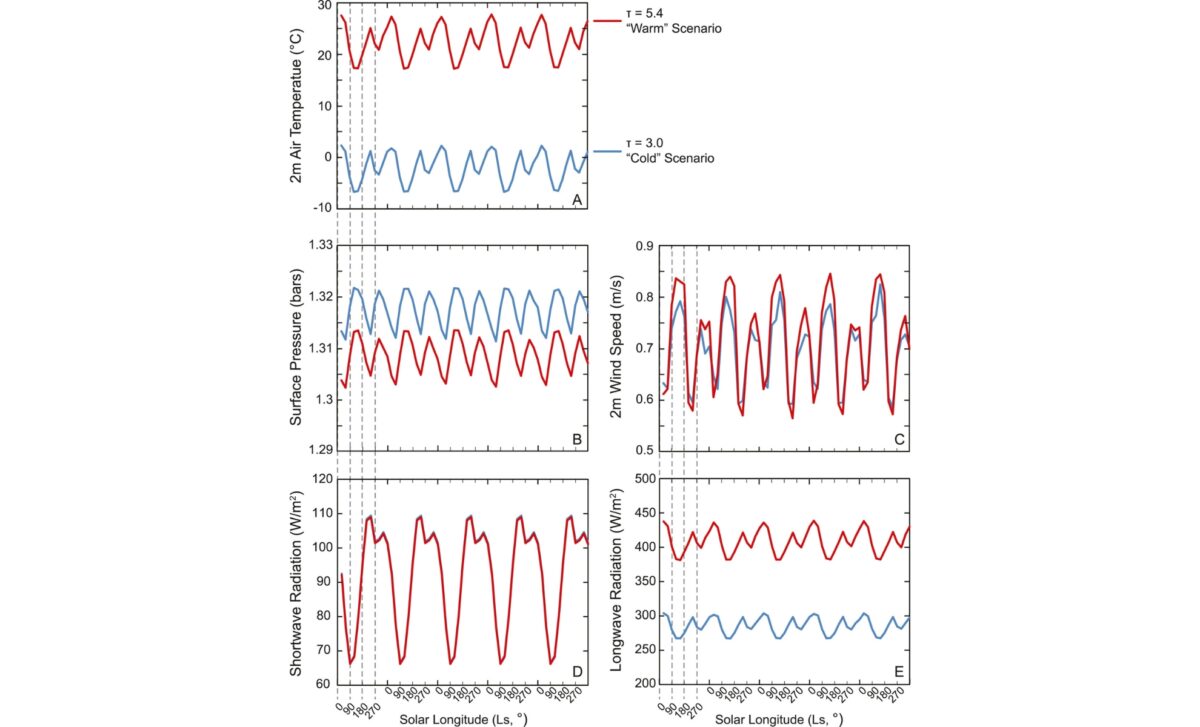

Over several years, they reworked the model to simulate conditions on Mars around 3.6 billion years ago. The adjusted version, named Lake Modeling on Mars with Atmospheric Reconstructions and Simulations (LakeM2ARS), took into account Mars’s lower gravity, carbon dioxide-rich atmosphere, and greater seasonal swings. According to Professor Sylvia Dee, another co-author, adjusting the Earth-based model to Martian conditions involved a significant amount of debugging and experimentation.

Long-Term Lake Simulations Using Crater Data

Using data from Gale Crater, where NASA’s Curiosity rover has been operating for years, the team ran 64 simulations. Each case tested how a hypothetical lake would respond to Martian climate over 30 Martian years, equal to about 56 Earth years. Some scenarios resulted in lakes freezing solid and not recovering. In others, lakes developed a thin seasonal ice cover that disappeared during warmer periods, allowing water to remain liquid.

According to the study, the thin ice acted as an insulator, keeping lakes from losing heat too quickly and preventing significant evaporation. This behavior could explain the clean, undisturbed condition of ancient lake beds, which show no signs of scraping or damage from thick ice sheets.

The team plans to apply their LakeM2ARS model to other regions on Mars to determine if similar lakes might have existed elsewhere. They also aim to explore how changes in atmospheric pressure or subsurface water could have affected lake stability over time. As stated by Eleanor Moreland, “If similar patterns emerge across the planet, the results would support the idea that even a quite cold early Mars could sustain year-round liquid water.”