Editor’s Note: The following excerpts key findings from the Partnership’s ’26 employment forecast released December 11, 2025. All data are as of August ’25 unless otherwise noted. The complete report provides deeper context and detailed, industry-by-industry analysis of what is expected to motivate gains and losses. The full version can be found here.

U.S. Employment

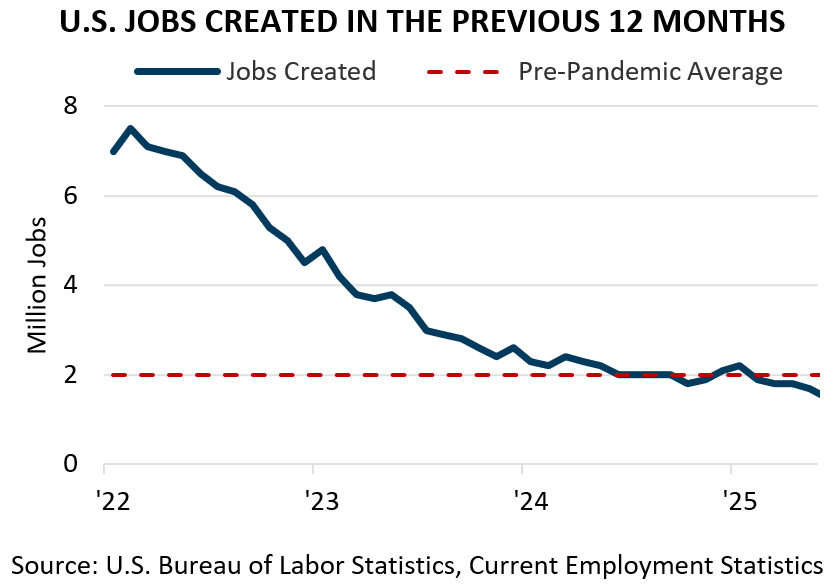

The U.S. labor market has slowed down from the dramatic pace of growth experienced in the immediate pandemic rebound. Between ’21 and ’23, the U.S. added an average of roughly 4.7 million workers each year as the economy went into overdrive to recover lost jobs. By ’24, the job growth rate came back to earth with a more typical 2.1 million jobs added during the year. In ’25, job growth slowed even further, falling below the pre-pandemic trend with just 1.3 million jobs added as the labor market encountered new headwinds.

Macroeconomic conditions shifted early in the year, with greater business uncertainty on issues like trade policy, interest rates, and the growing prominence of new A.I. technologies. Many businesses responded to this unfamiliar landscape by pulling back on expansion and hiring, choosing instead to emphasize cost discipline and improving the productivity of existing workers. As a result of these shifts, monthly U.S. job openings fell from 7.7 million to 7.2 million between January and August, while layoffs held steady at about 1.7 million over the same period. In other words, the job market slowdown simply reflects less hiring and not more firing. This is different from a recessionary pattern: the labor market is still expanding, just modestly, with employers pulling back on new hiring while holding on to the workers they already employ.

Even as terminations remain low, the U.S. unemployment rate has ticked up from an average of 4.0 percent in ’24 to 4.2 percent in ’25 as new job seekers enter a workforce with fewer available openings. The U.S. unemployment rate overall averaged at 6.2 percent in the decade before the pandemic – the lower rates of around 4.0 percent during the past few years are unusual over the longer course of U.S. history. So, while national unemployment rates have ticked up slightly in ’25, they remain below long-term norms.

The conditions that led to a slower job market are unlikely to fade quickly. Job growth should remain positive but subdued through the opening months of ’26, with a rebound possible later in the year. The national unemployment rate is expected to rise slightly, though it should remain below 5.0 percent.

U.S. Economic Output

Despite the softening labor market, economic output has continued to expand through the first half of ’25. Gross domestic product (GDP), the broadest measure of U.S. output, grew with the nation producing almost 24 trillion dollars of goods and services for the 12 months ending in Q2 ‘25. The GDP growth rate briefly turned negative in Q1 (-0.6 percent) as tariff uncertainty prompted firms to stockpile imported inventories and temporarily displace domestic production. However, growth rebounded quickly to 3.8 percent in Q2, before hitting an impressive 4.3 percent in Q3.

Bureau of Labor Statistics data shows U.S. manufacturing output rebounded in Q2 with 2.4 percent growth after a Q1 decline, led by greater productivity in durable goods.

A renewed focus on productivity, cost discipline, and the adoption of new A.I. technologies suggest that economic output will continue to outpace job growth. However, without broader business expansion and additional hiring, these forces are more likely to support moderate growth than to ignite a period of rapid acceleration.

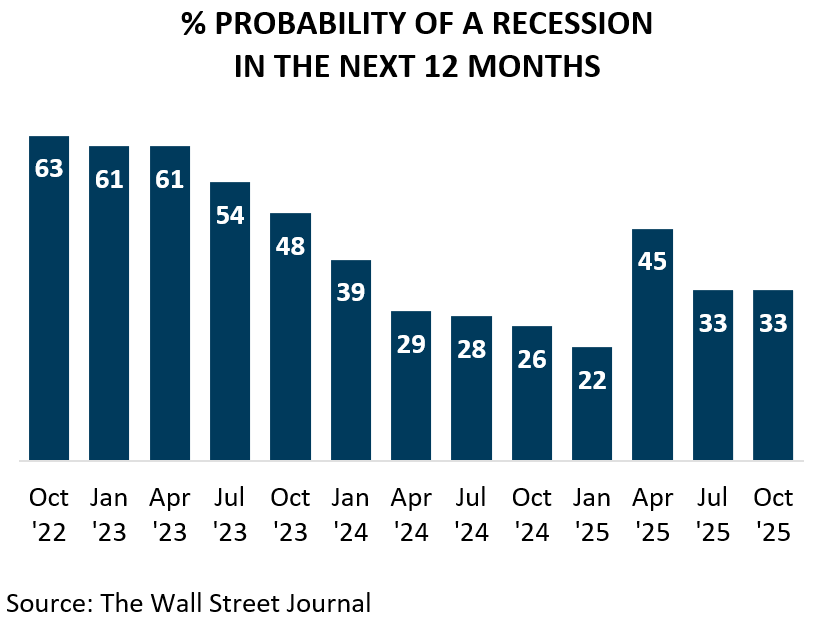

While this trajectory may be slower than what we have become accustomed to in recent years, it still represents forward momentum with relatively low odds of a recession. An October ’25 Wall Street Journal survey of economists puts the probability of a U.S. recession in the next 12 months at 33 percent. That figure is higher than the 22 percent reported in January, but lower than the peak of 45 percent reached in April, when uncertainty over trade policy was at its highest.