In some parts of our planet, the ground under our feet sinks so slowly that no one feels as it’s happening, yet those changes are observable with modern scientific instruments.

Satellite data has unveiled a captivating geological phenomenon beneath the Central Anatolian Plateau of Turkey – the Konya Basin – demonstrating that Earth’s crust is “dripping” under the country of Turkey.

This hidden geological marvel has intrigued scientists for years, prompting further investigation into its underlying causes.

Studying the “dripping” in Earth’s crust

How does a region that has been rising overall also hold a center that sinks, like a shallow dent forming in a tabletop that should look flat?

A team of earth scientists at the University of Toronto set out to answer that question, led by Julia Andersen.

Andersen and her team pulled together satellite measurements and several other kinds of Earth data to figure out what the crust and upper mantle are doing beneath the Central Anatolian Plateau.

They focused on the Konya Basin because it shows a clear pattern that stands out from its surroundings. The bowl-shaped area keeps deepening even while the larger plateau around it sits high and has risen over long stretches of geologic time.

Satellites and seismic waves

Satellite tools can track tiny changes in the ground over wide areas, and seismic waves from earthquakes can reveal odd zones inside the planet because waves speed up or slow down in different materials.

Put those views together and you can connect surface motion with what likely sits tens of miles down.

“Looking at the satellite data, we observed a circular feature at the Konya Basin where the crust is subsiding or the basin is deepening,” lead author Andersen explained.

“This prompted us to look at other geophysical data beneath the surface where we saw a seismic anomaly in the upper mantle and a thickened crust, telling us there is high-density material there and indicating a likely mantle lithospheric drip.”

Basics of plate tectonics

Plate tectonics explains how Earth’s outer shell breaks into moving pieces. Those plates ride on hotter, softer rock below, and heat from deeper inside the planet keeps material circulating slowly.

That movement builds mountain ranges, opens ocean basins, and sets up many of the earthquakes and volcanoes people know about.

Central Turkey sits in a complicated zone where large plates press, slide, and rearrange.

Those plate motions are important, but they don’t automatically explain why a round basin would sink inside a region that has lifted. To get the full story, science has to look deeper than the surface map.

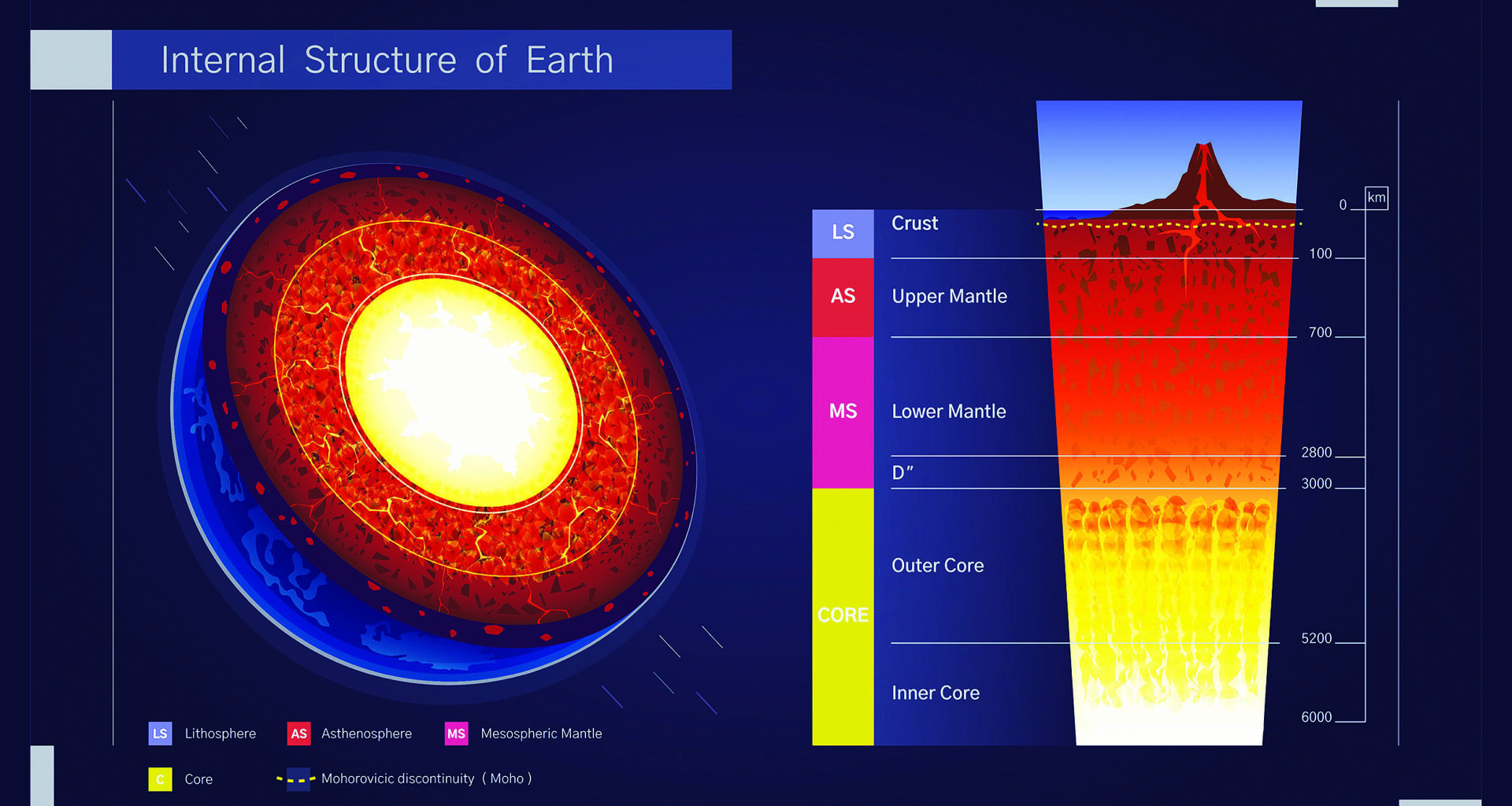

Diagram explaining Earth’s internal structure. The structure of the earth’s crust. Educational illustration. Model of the earth in cross section, layers of the earth’s crust. Click image to enlarge.Stages of Earth’s crust dripping

Diagram explaining Earth’s internal structure. The structure of the earth’s crust. Educational illustration. Model of the earth in cross section, layers of the earth’s crust. Click image to enlarge.Stages of Earth’s crust dripping

The study, published in Nature Communications, points to a process called multi-stage lithospheric dripping. In plain terms, parts of the lower lithosphere can become unusually dense.

When that happens, gravity can pull that heavy material downward until it peels away and sinks into the mantle below.

That sinking changes the balance of forces in the rock column. The surface can sag above the heavy, descending material, forming a basin.

Later, if the dense part detaches and drops farther down, the surface can rebound and rise because it no longer carries that extra weight.

Past studies report that the Central Anatolian Plateau has risen by about 0.6 miles over the last 10 million years as this kind of process played out.

“As the lithosphere thickened and dripped below the region, it formed a basin at the surface that later sprang up when the weight below broke off and sank into the deeper depths of the mantle,” says Russell Pysklywec, co-author of the study.

“We now see the process is not a one-time tectonic event and that the initial drip seems to have spawned subsequent daughter events elsewhere in the region, resulting in the curious rapid subsidence of the Konya Basin within the continuously rising plateau of Türkiye.”

Simulating Earth’s dripping crust

To test whether the idea makes physical sense, the researchers recreated the process with lab models. First, they built analogue layers that behave like the deep Earth in slow motion.

Next, they filled a plexiglass tank with a silicone polymer fluid to stand in for the lower mantle, added a mix of that fluid with clay for the upper-most solid mantle, and then poured in a top layer made of ceramic and silica spheres to act like crust.

Those materials don’t make a perfect copy of Earth’s crust, but they do enough to let scientists watch the same kinds of instabilities form and grow.

When a dense part starts to sag and detach in the model, it helps explain how a real lithosphere might do the same thing over millions of years.

“The findings show these major tectonic events are linked, with one lithospheric drip potentially triggering a host of further activity deep in the planetary interior,” Andersen concluded.

Earth’s dripping crust and exoplanets

The team also compared what they learned to the Arizaro Basin in the Andes of South America, which suggests this process does not belong to just one country or one plateau.

Mountain plateaus often involve thick crust, deep heat, and complicated stresses, so they can set the stage for dense lower layers to form and start sinking.

This kind of work also helps scientists think about other worlds. Mars and Venus don’t run on Earth’s familiar system of moving plates, yet their interiors still move heat upward and shuffle dense and light materials around.

If dense rock can peel off and sink without a plate boundary doing the pushing, it gives planetary scientists another way to explain big surface features on worlds that play by different tectonic rules.

The full study was published in the journal Nature Communications.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–