What is the future of downtown Dallas? Even for a place that is persistently described as “at a crossroads” and “in crisis,” the present moment seems fraught and precarious. AT&T is leaving, City Hall’s future is in question, a new convention center is coming and the Mavericks and Stars want new arenas. These factors are compounded by the grim shape of downtown’s streets and sidewalks, continuing struggles with homelessness, the fraying DART partnership and an alarming commercial vacancy rate.

How the city addresses these challenges in the coming months will determine its character both physically and figuratively for a generation or more.

My advice: Avoid rash decisions and learn from history. The current state of affairs did not arrive out of the blue; it is a product of decades of poor choices and general neglect. There is no quick fix for downtown, and attempts to find one will only exacerbate the city’s already considerable problems.

Dallas has been in a roughly analogous situation before. In 2001, Boeing was looking for a new corporate headquarters, and the competition came down to Dallas or Chicago. Dallas lost, and the principal reasons given were a dearth of cultural amenities and a lack of urban vitality. Dallas addressed the first of those problems by pouring capital into the stalled Arts District. In the years following, a handful of new parks — most notably, Klyde Warren — created attractive oases within and adjacent to the downtown core.

News Roundups

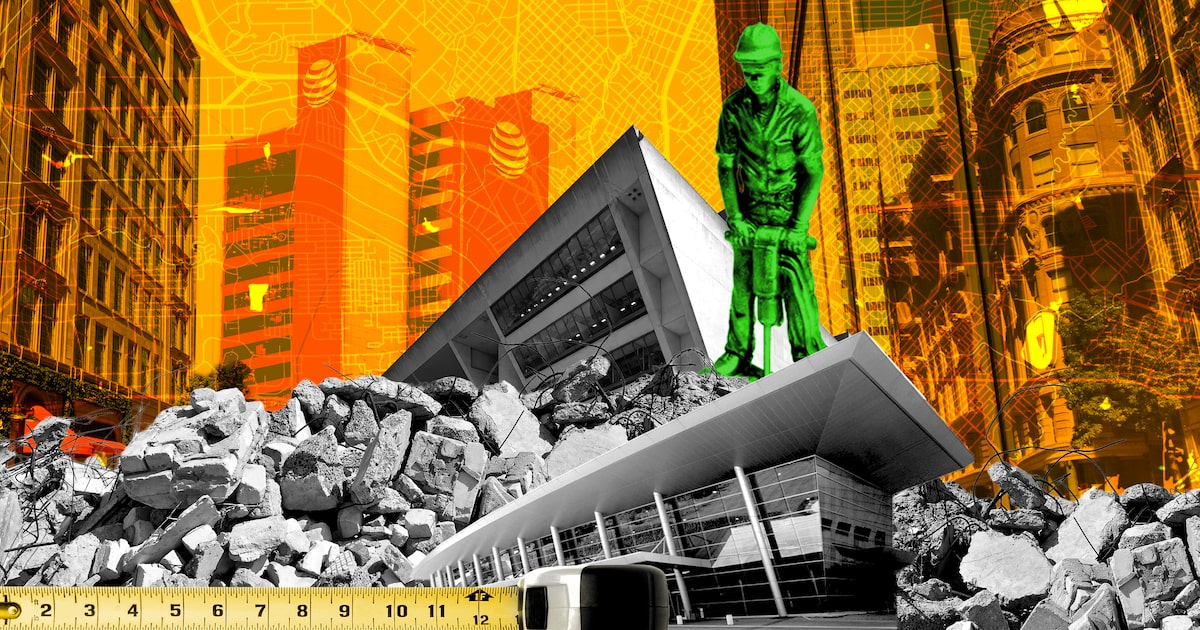

But the vitality problem persists, and it is the fundamental root of all the city’s issues. Trophy buildings — cultural facilities, an arena, a convention center — are not the answer, however much they might appeal to the developers who would profit from them and the politicians who can say they have fostered progress with their construction. Until the city repairs its urban fabric, the connective tissue between its trophies, it will forever struggle to become a vital place that attracts and retains residents, employers and visitors.

Surface parking lots: the scourge of downtown vitality.

Louis DeLuca / Staff Photographer

This isn’t exactly a revelation. Planners have developed any number of plans intended to repair and invigorate the downtown core, but the city fails to follow through on them at the requisite scale, due to lack of will or lack of funds or both. Instead, Dallas resorts to giant swings (like a new convention center) and chases easy money, even when it’s counterproductive to do so.

The decision, last year, to license new digital advertising boards to be placed on city sidewalks is an example of its misguided, short-term thinking. Narrow, cluttered sidewalks are an obvious detriment to downtown’s walkability and general appeal, but instead of working to ameliorate those problems the city has decided — for a relatively modest payment — to further aggravate them.

Conversely, rival Houston is transforming a stretch of its downtown into a pedestrian thoroughfare with trees and shade structures designed to mitigate heat.

The most important step Dallas can take if it hopes to become a more appealing place is to commit itself to reversing generations of auto-centric urban planning. Decisions on sidewalk and street widths, directionality and signal timing need to be determined by what is best for pedestrians, not by traffic engineers who inevitably favor the flow of cars and trucks.

A top priority should be making the core a more unified, easily navigated place rather than a series of discrete districts cauterized by high-speed traffic corridors. The north-south streets of Griffin, Lamar and Pearl are too wide and forbidding for pedestrians, and effectively slice downtown into disconnected sections. Landscaped medians and other traffic calming measures would do much to create a more seamless environment.

Another urgent priority: addressing downtown’s many vacant surface lots, aesthetic blights that discourage walking and feel unsafe to pedestrians. At the least, the city needs ordinances that require property owners to landscape the edges of these lots to shield pedestrians and create more appealing environments.

Downtown’s streets, scaled to automotive traffic, are an impediment to walkability.

Brad Loper

It should also start taxing these empty spaces based on the true value of the land they occupy. For example, the annual tax bill for Fountain Place, the rocket-shaped downtown tower, is roughly $3.2 million, according to the Dallas Central Appraisal District. The two surface lots comprising an entire city block directly across Ross Avenue are taxed at roughly $160,000. Changing tax rates on vacant land would encourage building on those lots, bringing in much-needed revenue that could be put toward downtown infrastructure improvements.

Dallas, meanwhile, is placing a good many of its eggs in the very large basket that is the remaking of the Kay Bailey Hutchison Convention Center. That project’s success in reinvigorating downtown will be determined by how the large swath of adjacent land, roughly 30 acres, is developed. That is more than enough space to build a new arena, obviating the need to demolish City Hall for that purpose. (There are several other sites in the area that could also accommodate an arena, as a group of leading Dallas architects recently demonstrated.)

Related

That the city is moving forward on this enormous project without a concrete plan for that space is disturbing in and of itself. The last thing the city needs is a repeat of Victory Park, the anodyne development hitched to the American Airlines Center that, more than two decades after its inception, has only begun to find traction as a vibrant community — and may lose it if its primary tenants depart.

Instead of glass towers and cookie-cutter apartment blocks, the city should be looking to create a human-scaled, mixed-use community using sustainable materials. And instead of delegating this project to corporate developers and their corporate architects, its design should be driven by local practitioners in consultation with the downtown community. This is an opportunity to let the city’s leading independent architects — designers who understand Dallas — create something that truly distinguishes the city, speaks to its character and is built to last.

Finally, Dallas needs to preserve and restore its iconic City Hall. Moving city government from I.M. Pei’s building, and potentially demolishing it, will solve none of downtown’s longstanding problems. In evaluating the building’s future, Dallas might consider the example of New York’s Penn Station, a monumental work of architecture derided as dilapidated in the 1960s, and torn down for a development including an arena. The city has regretted that decision ever since.

It was in that same time period that Dallas began tearing up its core in the name of economic development, transforming its dense, walkable downtown into a place oriented to the car. If it is to regain its sense of vitality and appeal, it will need to repair that damage, not exacerbate it by demolishing its existing architecture.

Letters to the Editor — Mushroom House, downtown Dallas, ICE agents, DART, Venezuela

Letters to the Editor — Mushroom House, downtown Dallas, ICE agents, DART, Venezuela

Readers are sad Dallas is losing some iconic buildings; hope downtown Dallas can be saved; ask questions about ICE agents; wish we’d be smart about DART; and support the takeover of Venezuela.

Lamster: The 20 most significant demolitions in Dallas history

Lamster: The 20 most significant demolitions in Dallas history

With City Hall’s future in question, a look back at the city’s history of architectural destruction.