It’s been two years since I first met my Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR) therapist. I tell myself I am much better than the day I met her, but I don’t always believe it. I still have moments when I completely shut down and feel unattached to anyone and anything. I still sometimes find myself uncontrollably crying. My entire body will still periodically start violently shaking, and the brain-piercing headaches still show up. However, it happens much less often, and the episodes are shorter. I still don’t always know what triggers these reactions, but I now know what they are, and I am able to find my way back from them more quickly.

I first started EMDR after a visit to the emergency room for what I thought was a heart attack. My wife Lori had died two years earlier after a 23-year pugnacious fight with a malignant brain tumor. She was 28 years old when she was first diagnosed. We were told she would be dead by 30, but she refused to go without a fight, and she refused to let the treatments or the physical and cognitive issues she experienced get in the way of how she wanted to live her life.

Lori started her own company, skied, hiked and traveled the world. And, in exchange for living a life filled with adventure, she accepted that she would periodically have a seizure and collapse on the street wherever she had been standing.

Every three months, our lives would stop for a week while we waited for the results of an MRI that would tell us if our love affair was over. Along the way, she ended up having four brain surgeries, more rounds of chemotherapy than I have fingers and toes, and 70 days of radiation to her head. When the tumor finally won, it was only after it exacted its cruelest revenge. Lori not only lost her dignity, but she also spent a year fully paralyzed from head to toe, including her vocal cords and eyes. She was left fully aware but unable to see the world around her or communicate. I had a front row seat to witness the tumor’s mendacity, but without any ability to ease Lori’s suffering.

To give Lori the support she needed to keep living, I had to sacrifice the life I knew. I did so willingly and without a moment’s thought. I loved her with my entire being and could not imagine my world without her. But when she died, I never realized all that I had lost along the way.

I lost my ability to care about anything beyond caring for her, lost all my hopes and dreams, lost thinking or even caring about a future, and lost any emotion tied to the life and death decisions we were making every day. I also lost my ability to show fear, sadness or pain in response to her disease because I felt I had to be strong for her. Ultimately, I lost my way and any connection to anyone else. There was no time to feel, much less grieve, what I was experiencing. I learned to move forward by just shutting down the loss as quickly as possible, burying my emotions and pressing forward. I dedicated myself to merely solving whatever problem was directly in front of me, and then pretending everything was normal.

After Lori died, I still found it impossible to grieve. I lived in a heightened state of awareness, always ready to react. I would be filled with uncontrollable rage at the drop of a pin. I had no empathy for whatever someone else might be going through and found myself severed from any connection to the rest of the world. Despite how intense and debilitating this experience was, I hid my struggle. To the outside world, I appeared fine. I went to work every day, saw friends, and even started mountain biking, but I wasn’t actually present for any of it. I felt cold, distant, and trapped. It was as if I was floating above the world, watching it beneath me, but not part of it.

When I was home, I sat in the dark in silence. That is where I felt safe. Often when I ventured out, I would turn a corner and suddenly find myself crying and with a headache so severe I had to sit down on the sidewalk. One minute I could be driving my car, and the next I had to pull over because I was shaking so badly I couldn’t hold the steering wheel. I had no idea what was triggering these bouts and no idea how to control them, so I just sat still and waited until they were over.

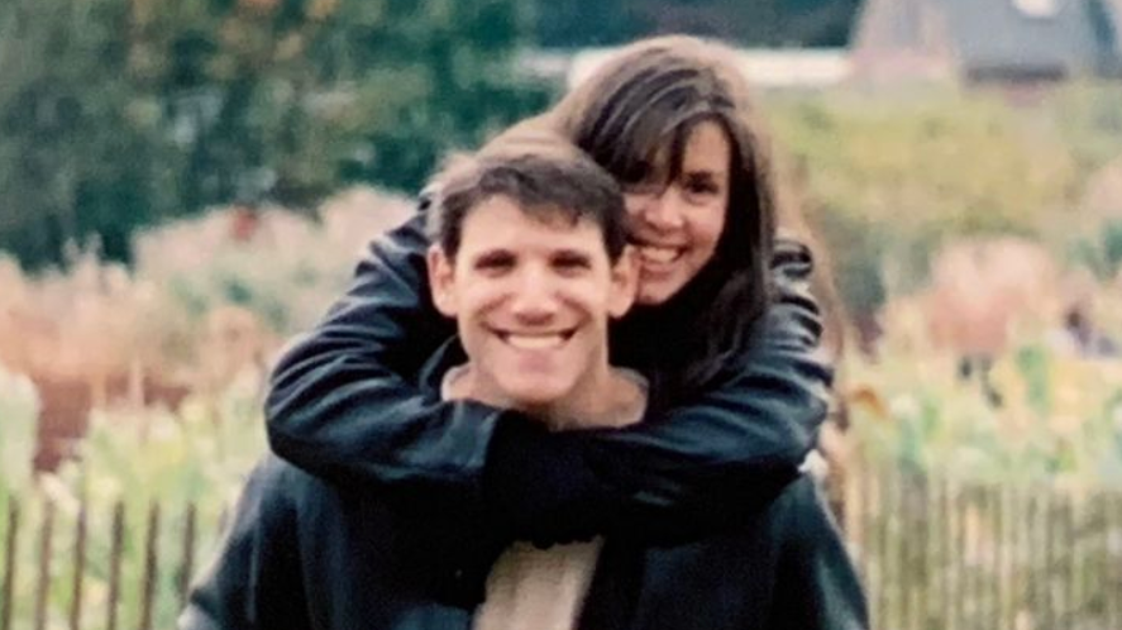

The author and Lori pumpkin picking in Eastern Long Island, New York.

The author and Lori pumpkin picking in Eastern Long Island, New York.

Courtesy of Jon Kortmansky

A little over two years after Lori’s death, I woke up in the middle of the night with a crushing pain in my chest and difficulty breathing. I thought I was dying, and I was ready for death. I actually only called 911 because I had made a promise to Lori years earlier that I would not die in the apartment.

When the EMTs arrived, my symptoms were indicative of a heart attack, and they pumped me full of the drugs to prevent any further damage. After five hours of tests in the hospital, I was told I hadn’t had a heart attack: I was in a constant state of panic. Even while I was sleeping, it was both absolutely shocking and not the least bit surprising.

I confided in a friend who had been in the military, and he told me, “I know these symptoms; you’re suffering from trauma. You should try EMDR.” Those four words changed my life.

I did a bit of research on EMDR, a treatment that helps people process traumatic memories, and watched some YouTube videos, but I still didn’t really know what it was or how it worked. However, I knew that something needed to change. I couldn’t keep living — if you could call it that — the way I had been. I didn’t want to go through life disengaged, angry, unable to focus, and experiencing my unpredictable and uncontrollable episodes of shaking, crying and headaches. I couldn’t sleep, and when I did, I would awake in the middle of the night from nightmares that I had to remind myself were not real. Worst of all, I was completely indifferent to everyone and everything. I felt like I was trapped inside a box with no door, alone with years of agonizing memories flashing in front of me over and over again.

My first EMDR session was simple enough. My therapist had a gentle demeanor and a kind face. She directed me to a brown couch with two small pillows, beside a small table with a box of tissues. I noticed there was no coffee table, and my therapist was seated directly in front of me.

She began the session by explaining how the process would work. Each time we met, I would spend up to two hours reliving all of the memories that haunted me in excruciating detail. She emphasized that this would not be talk therapy and that I was going to re-experience my trauma in a safe place.

She told me that when some people suffer extreme trauma, their brain doesn’t organize their memories so that they remain in the past. Instead, they keep reliving them as if they’re still happening. I asked her if I could just forget them. She kindly and gently explained that I would have to live with those memories forever, but that if I did the work, I could forge a new path and begin life anew.

I had no idea if EMDR would work for me, or how, but in that moment, I was so desperate for relief, I simply accepted what she was telling me.

My first few sessions were incredibly hard. I wore earphones and held vibrating stones in each hand. My therapist began the session by asking me to describe a memory. Then she turned on the EMDR machine and told me to notice my thoughts and what I was feeling in my body as I thought them. I initially felt and thought nothing, but soon, I was overcome with waves of physical and emotional reactions: shaking, crying and headaches. Anger, fear and guilt surfaced, and I felt them intensely, but I often couldn’t find the words to describe what I was feeling.

Sometimes I would ask my therapist if we could stop. She always said yes, but she would also ask me if that was what I really wanted. My response was usually no, but sometimes I felt completely overwhelmed by what I was experiencing. She taught me how to recover from the sessions and ground myself. For a long time, I couldn’t tell if I was making any progress, but about six months into my therapy, something happened: I found the strength to buy a new bed. I know this sounds trivial, but I was still sleeping in the bed where Lori died, and it was the place where she had suffered the most.

Towards the end of Lori’s life, she could not swallow and would vomit uncontrollably while she slept. Because of this, she would aspirate constantly, and that liquid poured into her lungs, but due to her paralysis, there was no way to know that she was having difficulty. There was no coughing — nothing. Once in a while, a tear drop might fall from her eye, and I knew that she was suffering.

The day that Lori died in that bed, she was drowning in her own body fluids. There was nothing I could do except watch as she suffered for hours until it was over. I knew I should have bought a new bed the day after she died, but I couldn’t bring myself to do it. Finally, six months in EMDR, I finally could, and I did.

The author, right, and Lori, left, taking in the sunset at First Encounter Beach, Eastham, Massachusetts.

The author, right, and Lori, left, taking in the sunset at First Encounter Beach, Eastham, Massachusetts.

Courtesy of Jon Kortmansky

Other new signs of my healing began to appear. Suddenly, I started to remember the names of people I met. I was able to engage in conversations. I recognized things that might be triggers, but more importantly, I was able to calm myself when I experienced a trauma episode. I started sleeping.

My friends and family noticed I was smiling, and they said I looked happier. They hadn’t seen me like this for years. I was no longer angry all the time, and I started to engage with the world around me again. I found the courage to take on new adventures and started making new friends. I even found the courage to start dating. Essentially, I started truly living again — and, importantly, I realized I wanted to.

So many people are struggling with trauma and grief, and yet, we rarely talk about it. Most of us don’t know what to say when someone is grappling with these emotions, or we’re afraid to say the wrong thing, so we say nothing. For those of us in the throes of trauma and grief, there is often an expectation that after some amount of time, a switch will flip and we’ll suddenly feel better. That’s not how it works. The numbness, emotional shutdowns, and lack of connection or trust in yourself and others can remain for years — even decades. It can destroy relationships, choke joy and make you pull away from the people who might help you move forward.

I found the hardest part about dealing with my trauma is that, for a long time, I thought I was alone. I was afraid to discuss the pain I was feeling with friends and family because I did not know how to explain what I was feeling, but also because I worried I wouldn’t be understood or even believed. When I did try to discuss it, the responses made me upset or feel even more isolated: “You’re still grieving, just give it time”; “Maybe you’re depressed. Have you thought about taking medication?” I often felt pity from people, as if I was damaged and not suffering with something real.

I loved Lori with everything I had, and I’m grateful that she was in my life for as long as she was. I do not regret putting her life ahead of mine; I would do it again in a heartbeat. But those years took a toll on me that I didn’t anticipate, and after her disease had already taken so much from me, the memories of it continued to wreak havoc.

EMDR helped me recognize that I needed to find the courage within myself to want to change, and it gave me the strength and tools to do so. I know that I may always struggle with painful memories and moments where I may be overwhelmed by the trauma I have been through, but I also know that I have and will continue to heal, and am in a much better place. EMDR may not be the right tool for everyone, but speaking up and asking for help is the first step towards finding peace. We don’t have to stay locked inside our nightmares.

I have a lot of life left in me, and I want to live as fully as I can.

Jon Kortmansky, a New York City lawyer, is writing a memoir celebrating his life with his beloved late wife Lori — and how the enduring strength of her love guided him to discover new hope, love and joy in his next chapter. For more on his story, follow him on Instagram @jonkortmansky.

Do you have a compelling personal story you’d like to see published on HuffPost? Find out what we’re looking for here and send us a pitch at pitch@huffpost.com.