In 1922, while on tour with Ruth St. Denis and Ted Shawn, Martha Graham arrived in Chicago. In the Art Institute, she was arrested by the sight of an abstract painting. “I nearly fainted because at that moment I knew I was not mad, that others saw the world, saw art, the way I did. It was by Wassily Kandinsky, and had a streak of red going from one end to the other. I said, ‘I will do that someday. I will make a dance like that.’”

One hundred and four years later, that dance, Diversion of Angels (1948), a meditation on love, returns to Chicago as part of the Martha Graham Dance Company’s centennial tour, along with Lamentation (1930), Graham’s iconic solo on grief; Chronicle (1936), an anti-war work created after Graham declined the Nazi invitation to dance at the Olympic Games in Berlin; and En Masse, a new work by Hope Boykin, created in part to Leonard Bernstein’s Mass, which was commissioned for the opening of the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts in 1971.

Built on the breath, the simple inhale and exhale magnified through the expression of a torso that sobs, gasps, laughs, and screams in ecstasy, wonder, and despair, and that undulates with life and strikes against the walls of the universe to resonate to the core of the viewer and burn an afterimage into the retina that remains long after the body has cycled through atoms and eras—this is the power of Martha Graham’s movement.

“Graham was the most famous, most controversial, and most prolific of all the modern dance pioneers, and her school and company the longest in operation in the modern dance world,” wrote Marian Horosko in Martha Graham: The Evolution of Her Dance Theory and Training 1926–1991. Thirty-five years beyond that pronouncement, these assertions still ring true. Like fellow modernists Stravinsky, Picasso, and Frank Lloyd Wright, Graham made an indelible mark on her art—a fierce cry of woman, power, and emotion—one that resonates through the companies that flowered from her dancers, including Paul Taylor and Merce Cunningham, and her students, including Alvin Ailey, Twyla Tharp, Lin-Hwai Min, and Madonna.

The Martha Graham Dance Company

Sat 1/24, 7:30 PM, Auditorium Theatre, 50 E. Ida B. Wells, 312-341-2300, auditoriumtheatre.org, $40.98-$151.65

American Icons, 2/19-3/1, Thu–Fri 7:30 PM, Sat 2 and 7:30 PM, Sun 2 PM; Joffrey Ballet at Lyric Opera House, 20 N. Wacker, 312-386-8905, joffrey.org, $46-$201

Winifred Haun & Dancers, First Draft 2026, Sat 2/28 7 PM and Sun 3/1 3:30 PM, Visceral Dance Center, 3121 N. Rockwell, winifredhaun.org, $49 general admission, $75 VIP (Sun only, includes postshow wine reception)

Most recently seen in Chicago over a decade ago in the 2015 Chicago Dancing Festival, the Martha Graham Dance Company returns to the Auditorium Theatre with a full program for the first time in 43 years, within a season of performances celebrating women leaders.

At 100 years, the Graham Company not only stewards and performs Graham’s 181-work repertoire, but it also regularly commissions new works by contemporary choreographers.

Martha Graham Dance Company in Hope Boykin’s En Masse, a new work created in part to Leonard Bernstein’s Mass Credit: Luis Luque

Martha Graham Dance Company in Hope Boykin’s En Masse, a new work created in part to Leonard Bernstein’s Mass Credit: Luis Luque

“We were conscious of aligning our one hundredth anniversary–Graham100–with America 250,” notes Janet Eilber, who began dancing with the company in 1972 and assumed the role of artistic director in 2005. The discovery of an unused piece of music created by Leonard Bernstein for Graham sparked the idea for a new commission. Just 49 seconds in length, the piece has been arranged by composer Christopher Rountree into a theme and variations and juxtaposed with sections of Bernstein’s Mass.

“Bernstein and Martha were both social activists in their era,” Eilber says. “That seemed like the right thing to bring forward right now in America, that art has an activism about it. We turned to Hope because we wanted a woman—an American woman.” Boykin also came with the unique experience of performing with Alvin Ailey, who had been the original choreographer of Bernstein’s Mass, and of choreographing the revival of the work for the 50th anniversary of the Kennedy Center in 2022, making the creation of a new work also a study in the task of upholding and transforming legacy.

Yet even when restaging Graham’s past works, Eilber describes a process that is alive with variation and revision, with an archive that preserves staging notes and cues, reviews, photos, and recordings of different dancers performing the work.

“Martha was constantly changing things to suit the power of the dancer who was taking on the role,” she says. “She lived so long and directed so many generations of dancers, so we have many versions of her direction of things.” Crucially, work is often passed from dancer to dancer with coaching from others who have danced the roles before. “I danced the Woman in White in Diversion of Angels my entire time with the company,” she says. “And since I left the company in the early 80s, any number of other women have danced Woman in White. So we have many generations of Graham family who are happy to come in and pass on the tradition.”

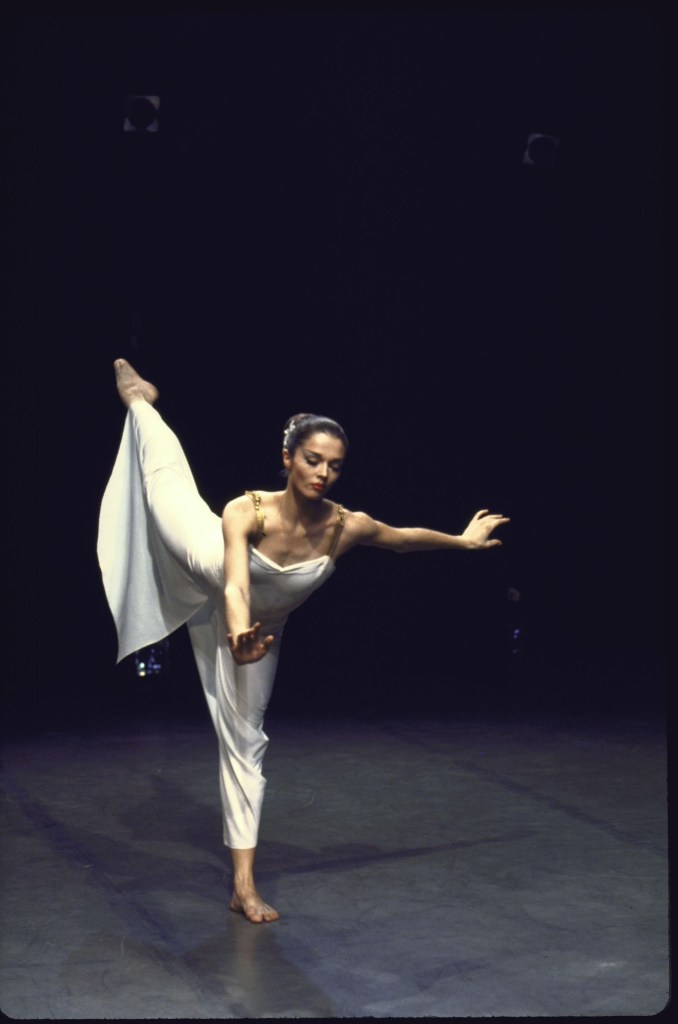

Janet Eilber in an earlier performance as the Woman in White in Martha Graham’s Diversion of Angels Credit: Martha Swope

Janet Eilber in an earlier performance as the Woman in White in Martha Graham’s Diversion of Angels Credit: Martha Swope

Eilber speaks with reverence about the many dancers who began the work with Graham and who continue to sustain its spirit. “In the 30s, this group of 12 young women who were the company and Martha traveled by train all over the country with this new art form that nobody really understood, and a lot of people didn’t like. They were putting down roots for us—and that generation went on to teach at different universities around the country. Those women are foundational to our 100 years—and everything springs from their dedication to Martha. They are the basis of our 100-year legacy.”

Here in Chicago, Graham’s legacy is living and evolving—as technique, as choreography, and as a way of being that continues to pulse with passion, motion, and deeply felt emotion.

Sandra Kaufmann

A native of Brookfield, Illinois, Kaufmann is the founding director of the dance program at Loyola University Chicago and danced with the Martha Graham Dance Company from 1989 to 1999. She served on the faculty of the Martha Graham School of Contemporary Dance and as artistic director of the Martha Graham Ensemble. Sandra continues to work actively with the Martha Graham Center, teaching in their international summer intensive workshop and serving as a regisseur staging the repertory of Martha Graham throughout the country.

My time at Graham coincided with a very dark period—after Martha’s death, during the company’s collapse, and before its rebirth under Janet Eilber. Seven dancers left immediately after Martha died, and the company had to rebuild almost from scratch. I was in the second company at that time.

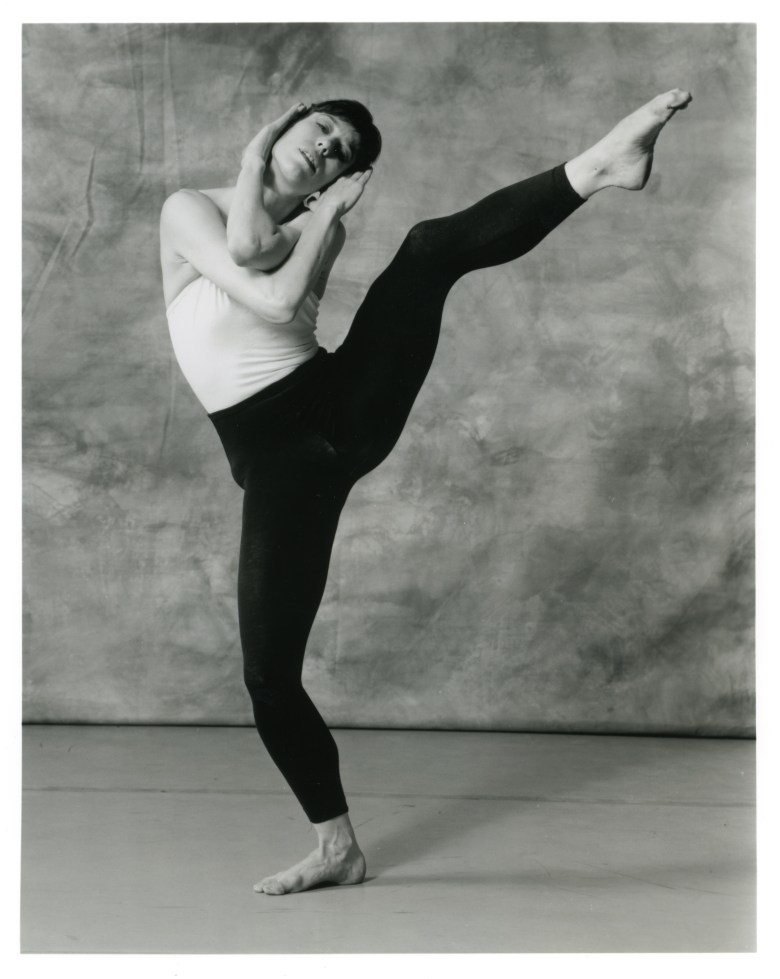

Sandra Kaufmann Credit: Steven Pisano

Sandra Kaufmann Credit: Steven Pisano

Ron Protas was in charge then. [Protas, who died in October, was named as Graham’s heir and had a contentious tenure as artistic director of the Martha Graham Center of Contemporary Dance, culminating in lawsuits over control of Graham’s dances that Protas lost.] He ultimately drove the company into the ground. We did our best to keep it alive, and we did some good work, but it came at great personal cost. During Ron Protas’s leadership, the Graham Company never toured to Chicago. There was no Graham presence here throughout the 1990s.

However, Graham’s legacy in Chicago was very real. Pearl Lang, who danced with the company and was the first to take Martha’s roles, was from Chicago. She grew up here and attended the University of Chicago Laboratory Schools. Pearl took a strong interest in me when I arrived at the Graham School, partly because I was a choreographer like her, and partly because I was from Chicago. She had theories about how dancers moved based on where they grew up—midwestern dancers, she believed, had a more spacious physicality.

Another crucial Chicago connection is Joseph Holmes, who was Pearl Lang’s student at the Alvin Ailey School. In the 1990s, the Ailey School letterhead listed Alvin Ailey and Pearl Lang as its founders. Joseph Holmes later came to Chicago and formed the Joseph Holmes Chicago Dance Theatre—the first professional dance company I ever saw. I encountered them at the Illinois High School Dance Festival, performing Oh Mary, Don’t You Weep. I had never trained in dance, but that performance changed my life. I didn’t know what I was seeing, but I knew I needed to dance.

Joseph Holmes’s company trained in Graham technique, taught by Harriet Ross. There was a strong relationship with Stephanie Clemens’s Academy of Movement and Music in Oak Park. The company rehearsed there, and students who progressed far enough could sit in on company class. I worked my way up to that point, witnessing Harriet Ross, Ariane Dolan, and the company dancers up close. I remember bursting into tears, overwhelmed by what I was seeing.

The lineage continues through the Chicago Academy for the Arts. For over 25 years, the Academy maintained a Graham-based modern program, taught by Randy Duncan, Deb Goodman, and me. Many dancers from the Academy have gone on to the Graham Company. Deeply Rooted Dance Theater also carries this lineage; their aesthetic remains strongly Graham-informed, even as it blends Horton and Ailey influences.

At Loyola, we’ve been building a Graham program from scratch. Deborah Goodman is the foundation of that program. She teaches the contraction in a way very few people still do. We now have a small but meaningful pipeline of students entering the Graham School. One of our recent students, Isaac Jung, a Korean American dancer, was just accepted.

So while the Graham Company itself wasn’t present in Chicago for many years, the lineage never disappeared. It lived through Pearl Lang, Joseph Holmes, Harriet Ross, the Chicago Academy for the Arts, Deeply Rooted, and now through Loyola. These are the active pods of Graham legacy in Chicago today.

I went to Northern Illinois University because, where I come from, people don’t go to college—but I knew I wanted to. I had an academic scholarship and didn’t know much about their dance program. I had seen them perform a ballet at the high school dance festival and thought, “Maybe I could get some ballet training there.” My goal was very clear: I wanted to be a high school dance teacher, like my gym-class dance teacher had been for me.

I double majored in education and theater dance. There was no dance education degree, so I got certified in health, which made sense to me—mind, body, spirit. Dance is all of that. That education background became incredibly important later. When I had to build the Loyola program and write curriculum for 15 or 20 years, I wasn’t intimidated. I had that pedagogy training from my undergraduate years.

At Northern, I encountered a strong dance program. Randy Newsom became my primary influence. He taught both Graham and ballet. I took off running: choreographing, acting, working in theater, doing film, cable TV—anything that came along.

I saw a photo of the London Contemporary Dance School in a book and thought, I have to go there. Jane Dudley, a Graham teacher, was there. Somehow, I made it happen. I had no money, but I got myself to London through an internship program. I offered to work for free in the office. They said yes, and suddenly I was inside the administration, right at the center of things.

I was 20. The director told me, “Sandy, I think you have a head for administration.” That was in 1987. But I was there to study Graham. My time in London gave me an international outlook—I traveled, lived in international student housing, met people from Africa, learned about apartheid. I came from a blue-collar background and knew almost nothing about the world. That changed everything.

“Graham was about getting to the essence of things—intentionally, psychologically, spiritually.”

Sandra Kaufmann

When I returned to Northern, I choreographed a piece about apartheid called A People’s Cry. In hindsight, it was deeply influenced by Graham technique—the contraction and release were clearly there. Northern took it to the American College Dance Association, and it was selected for the gala. Shortly after, I received a scholarship to the Martha Graham School. I hadn’t even danced in the piece—I had only choreographed it.

What drew me to Graham, from the very beginning, was this: Graham holds emotion in the body. It expresses psychological and emotional tension. That resonance captivated me and continues to captivate me. Graham was about getting to the essence of things—intentionally, psychologically, spiritually.

I feel a hunger for people to connect emotionally and to want that catharsis on stage physically. We were always taught as Graham dancers that we were athletes of God. We were serving something deeply spiritual. A Graham dancer is called. It’s people wanting to resonate at the deepest stratum, and they will sacrifice their body to do it. It takes energy like you cannot believe—and yet it’s cathartic because you get that back by enacting it.

Seeing the Graham Company return to Chicago now, with this program—Diversion of Angels, Hope Boykin’s work, Chronicle—it’s deeply meaningful. Diversion of Angels alone connects Kandinsky, the Art Institute of Chicago, Pearl Lang, and the lineage itself. Chronicle is one of Graham’s most explicitly political works—antifascist, urgent, and still painfully relevant.

It’s extraordinary that the company is only here for one day. But it’s powerful. And I hope audiences feel even a fraction of what I felt when I first saw Oh Mary, Don’t You Weep—that sense of recognition, of something profound speaking directly through the body.

Deborah Goodman

As a scholarship student to the Martha Graham School, Yuriko chose Goodman, a Chicago native, as her demonstrator, training her in the early technique and repertory of Martha Graham. She danced with Richard Move and Goldhuber/Lasky in New York and MOMENTA Dance Company in Oak Park. She is currently a lecturer in dance at Loyola University Chicago.

I started dancing in college at Northern Illinois University. Randy Newsom was the head of the program and the Graham teacher. Sandra Kaufmann choreographed A People’s Cry, a Graham-based work calling for an end to apartheid. I danced in it. It went to the American College Dance Festival, where Sandra received the national Graham scholarship for choreography, and I was the runner-up as a dancer.

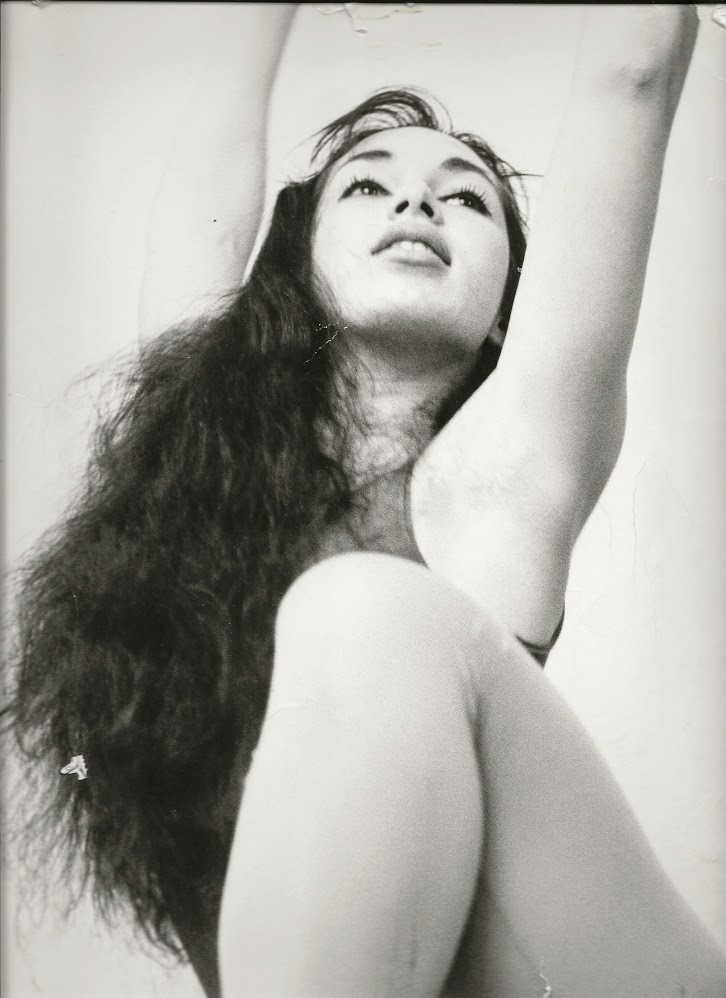

Deborah Goodman in Martha Graham’s The Cry (set by Yuriko from the original) at Oak Park’s Pleasant Home. The piece was presented by Winifred Haun & Dancers as part of Vision, Faith & Desire: Dancemakers Inspired by Martha Graham. Credit: Matthew Gregory Hollis

Deborah Goodman in Martha Graham’s The Cry (set by Yuriko from the original) at Oak Park’s Pleasant Home. The piece was presented by Winifred Haun & Dancers as part of Vision, Faith & Desire: Dancemakers Inspired by Martha Graham. Credit: Matthew Gregory Hollis

I was a geology major—space and planetary science—but my brother-in-law told me, “You can do geology anytime. You can only dance now.” So I went to New York.

Sandra and I were scholarship students together at Graham. We were roommates. We’re sisters now—more family than friends.

While there, I got very sick. I was told I had female hysteria and chronic fatigue syndrome. Five doctors told me I was dying—and that nothing was wrong.

I planned to come back to Illinois. Diane Gray, who was the director of the Graham school, called me and said, “You didn’t go to the scholarship audition.” I said no, and she replied, “Well, this is what you’re meant to do. We’re going to give you a full scholarship. It will be a demonstrating scholarship.”

At the time, you had to demonstrate five classes a week. She said, “You’ll start with one class a week and build yourself up. You’ll build your strength, because this is what you should be doing.” So I received a full scholarship at Graham.

I was a scholarship student when Yuriko was reconstructing Panorama. I was cast in it. I performed Panorama at City Center and then toured to Italy—the early 1990s performances.

I was also one of the dancers selected to reconstruct Sketches From Chronicle. The reconstruction process was remarkable. When Panorama was reconstructed, it was led by Yuriko. Later, when Sketches From Chronicle was reconstructed, Sophie Maslow was brought in because she had danced in it.

This was a period when Yuriko convinced Martha to revisit early works. Martha never wanted to look back, but Yuriko asked for her blessing. Martha agreed, and the reconstructions were so successful that she allowed them to continue.

Through these reconstructions, they realized that the technique had evolved over time. If dancers were going to reconstruct early works, they needed to understand the technique as it was originally practiced. So they began bringing in dancers in their 70s, 80s, and 90s—people like Ethel Winter—to teach early technique. We worked directly with these masters.

After Celebration, which was such a success, they committed fully to this process. That’s why my deepest mastery is in early Graham technique. When I teach, I focus on that foundation, because everything evolves from that seed—and that seed was entirely anatomical. If you understand what you’re doing anatomically, you can exaggerate any way someone asks without destroying your body.

After the Sketches From Chronicle reconstruction, I left the Center. About a year later, I ran into Yuriko on a bus. She had just begun teaching again and told me she was teaching at City Center. I took her class, and it was a revelation.

“Graham technique is a revolution toward humanity.”

Deborah Goodman

During a simple port de bras exercise, she suddenly said, “You’re going to teach. I don’t want to die with all of this knowledge. You’re going to teach.” For years, I assisted her in workshops and reconstructions, including Steps in the Street at The New School. Yuriko had a photographic memory for movement and was Martha’s demonstrator for years. She was an uncompromising artist. During that process, the 2002 tsunami occurred, and she made the students study the images and confront the reality of suffering before dancing. She told them, “You don’t need to pretend to be people in the 1930s. This is happening now.”

I understand that tension. I was in New York during September 11 and volunteered at Ground Zero. I didn’t take photos because it felt disrespectful, but now I realize that documentation is also a form of honoring and teaching.

That’s how I came to work with Yuriko, and she’s the reason I began teaching. She called me every day asking if I had a teaching job until I finally convinced the YWCA to let me teach a class.

Eventually, I began substituting at SUNY Purchase, teaching at Long Island University, and on my last day of class, Yuriko came in and taught the final. She asked me to list everything I had taught, then taught something entirely different to assess the students’ technique. At the end she said, “You did good. You’re fine.” Her brilliance, generosity, and rigor were extraordinary.

After September 11, dance work in New York dried up. I was dancing with three companies, then only one. I decided to leave New York. Sandra had been asking me to help start the dance program at Loyola. Within six days of calling her, I had a job dancing with MOMENTA, teaching at the Chicago Academy for the Arts, and teaching at Loyola. Six weeks later, I was in Chicago. That was 2006.

There’s a Chicago Academy for the Arts alum in the company now—Zachary Jeppsen-Toy.

My legacy is really in technique. Where I’m deficient in Graham is choreography. Sandra and I are a good team because I provide the technical foundation, and she brings the repertory.

Graham technique is a revolution toward humanity. It emerged alongside the suffragette movement—women discovering their bodies and inner lives, expressing anger, grief, and power without catering to the male gaze.

The technique exists to reveal the inner landscape in an abstract way, so others can see themselves in it. As Yuriko said about Lamentation: no one wants to see you cry—they need to see themselves.

Graham technique moves from muscles to bones to electricity. It’s about dancing from the deepest inner current.

Anne O’Donnell Passero

O’Donnell Passero danced with the Martha Graham Company from 2014 to 2023. Since moving to Chicago, she has taught at Hubbard Street, DanceWorks Chicago, and the Joffrey Academy and performed with the Lyric Opera of Chicago and Dance For Life. She is currently staging Graham’s Secular Games (1962) on the Joffrey Ballet, which will be performed in their American Icons program this February.

I danced professionally in New York for 16 years—ten seasons with the Martha Graham Company. I felt I was at a place where I wanted to explore new opportunities in the arts. Chicago has such a vibrant dance scene, and there was so much to explore here.

Now I’m staging Martha Graham’s work on the Joffrey Ballet for their 70th season—30 years in Chicago—and Graham’s 100th anniversary. It’s humbling to pass on Graham’s legacy rather than being the dancer myself.

I loved modern dance and Graham from the start, but I was especially influenced by mentors such as Jacqulyn Buglisi and Terese Capucilli, who worked directly with Martha Graham. What struck me was their presence. Someone could simply turn their head onstage, and it was jaw-dropping. Graham’s movement—its physicality, athleticism, and deep expression—felt so human and raw. I was drawn to its simplicity and nuance.

I traveled the world with the company. We performed historic works from Graham’s vast archive, but we also worked with contemporary choreographers the company commissioned. That range—dancing works from different eras and aesthetics—was an incredible opportunity.

I performed many roles that Martha Graham herself originated. Watching her dance them, then seeing how generations of dancers interpreted the roles, and finally finding my own voice within them—it was an honor. The experience shaped me profoundly as an artist.

Anne O’Donnell Passero as the Bride in Appalachian Spring Credit: Hibbard Nash

Anne O’Donnell Passero as the Bride in Appalachian Spring Credit: Hibbard Nash

Dancing the Bride in Appalachian Spring stands out as a memory. I began as a Follower and later took on the lead role. That role is incredibly honest—you can’t hide behind physicality. You have to fully commit to the storytelling. You’re onstage for half an hour without leaving, so you must stay present the entire time.

To prepare Secular Games, I studied original black-and-white footage from 1962—some of it without synchronized music—as well as later versions from the 1990s and the reconstructed 2019 version led by Janet Eilber, which restored the original music.

It complements the Joffrey dancers well. They’re very expressive and theatrical, and this work has athletic, balletic lines and a playful quality that suits them.

It’s also one of Graham’s lighter works, unlike many of her Greek tragedies. It hasn’t been performed very often, which makes it special. Graham created hundreds of works, and it’s exciting to bring lesser-seen pieces to life.

It takes time to develop the physicality of any technique, but Graham celebrated individuality. This piece has many individual moments and choices, which help the company connect to the work. It’s deeply human and playful, centered on relationships and interaction.

I’m incredibly passionate about Martha Graham’s legacy and grateful for the influence it’s had on my life. I hope people come see the performance at the Auditorium. I danced Diversion of Angels and Chronicle almost every year I was with the company. Some works never leave your body. I’m thrilled they’re bringing these classics to Chicago—they’re timeless and still resonate deeply. Graham’s work taps into something deeply human, and audiences feel it whether they know dance or not. That clarity of expression is powerful—and rare.

Winifred Haun

Haun is the founder and artistic director of contemporary dance company Winifred Haun & Dancers. She studied Graham technique while performing and touring with the Joseph Holmes Chicago Dance Theatre from 1985 to 1991. In 2013 and 2014, Haun and Chicago choreographer Lizzie Leopold curated the three-part series, Vision, Faith, & Desire: Dancemakers Inspired by Martha Graham, which took place at the Ruth Page Center for the Arts, Pritzker Pavilion, and Pleasant Home and featured works by Haun, Leopold, Ayako Kato, Peter Sparling, Lisa Thurrell, Paul Sansardo, Jeff Hancock, Randy Duncan, RE|dance, Alex Springer and Xan Burley, and Graham’s The Cry (set by Yuriko and danced by Deborah Goodman), as well as variations on Graham’s Lamentation.

The first time I took Graham with Joseph, I thought, “I’m home. This is me. This is my place.”

I was an apprentice for six months. Looking back now, I realize Joseph’s model was similar to Alvin Ailey’s early model. When Ailey started his company, there weren’t many Black dancers with formal training, so training was built into the company. You joined the company, and you trained. Joseph danced with Ailey for about a year—long enough to absorb the approach. He probably couldn’t afford to stay in New York in the 1970s, so he came back to Chicago and started his company in 1974. That ethos—”I have to train my dancers”—was central.

Winifred Haun Credit: Michael Mauney

Winifred Haun Credit: Michael Mauney

I had Graham three days a week with Harriet Ross for six—almost seven—years. I had not done it before, and I was completely clueless. They made me take beginning classes with the teens because I really didn’t know anything. We had workshops twice a week with Joseph in Graham technique. Then he died of HIV, and Harriet and Randy took over the company. Harriet ended up teaching us much more intensively, and I learned a tremendous amount from her.

“I think Graham was in pursuit of truth. The body doesn’t lie.”

Winifred Haun

I began choreographing on the Joseph Holmes scholarship students, and when I left the company, they became my first company. Scholarship students got free classes, but they had to clean the studio. We’d have class, then a break around 1 PM when they were supposed to do chores. I’d say, “Hurry up, get your chores done—I’m going to choreograph on you.” I choreographed almost every day for an hour during lunch, sometimes after rehearsal. Over those two years, I probably made three or four works that way.

I wouldn’t describe my work as looking like Graham aesthetically, but I do favor certain forms. What I value most is the strength and clarity Graham technique builds—especially through the torso. When I audition dancers, I don’t read résumés. Almost without fail, the dancers I respond to most have studied Graham at some point. There’s a clarity of movement I recognize.

I especially love Graham’s Steps in the Street. Walking is profoundly human. We’re the only animals that walk the way we do, and when someone simply walks across a stage, it’s deeply relatable. What Graham does so well is create movement that allows people to project themselves onto it. When the movement is clean and unaffected, audiences can write their own stories.

I think Graham was in pursuit of truth. The body doesn’t lie. Her work revealed truths about people, about life, about the world. That’s what I’m after, too.

Harriet Ross

Ross served as associate artistic director for Joseph Holmes Chicago Dance Theatre. She was the general manager of the Joffrey Ballet from 1995 to 2006 and the founding managing director of the Gerald Arpino and Robert Joffrey Foundation. Ross was instrumental in creating Dance For Life in 1992 and founded the Dancers’ Fund (now the Chicago Dance Health Fund) in 1994.

I was a little girl from Borough Park, New York, an Orthodox Jewish neighborhood, and most of my family was. So I had to sneak out on Saturdays to go take class—and I snuck. When I was a junior in high school, [Graham dancer and teacher] May O’Donnell needed a junior company because she was doing the Brandenburg Fifth Concerto. [O’Donnell’s 1956 piece Illuminations used Bach’s music.] She needed a lot of little people who could prance and do stuff like that. And I was one of them.

Harriet Ross Credit: Milton Oleaga

Harriet Ross Credit: Milton Oleaga

I went to Juilliard from 1957 to 1961. My teachers were [Graham company dancers] Yuriko, Ethel Butler, Helen McGehee, Bertram Ross, Donald McKayle. This is the group that shaped my absolute love of Graham technique.

I am a person who believes that you need strong ballet and strong Graham technique—ballet for your limbs and Graham for your torso. You put those parts together, and you’ve got quite a dancer. That’s how I trained the Joseph Holmes Chicago Dance Theater.

I moved to Chicago in 1975. I was taking a class, and Armgard [von Bardeleben, Graham dancer and director of the Graham school] was teaching the class as a guest. Joseph and his company happened to be in that class. They were all excited because he had taught them his version of Graham technique, and they were going to be outstanding. Instead, Armgard was checking counts with me. So after class, [Holmes] came up to me and said, “Who are you?” I told him. He said, “Well, would you teach a class at my studio?” I said, “Sure. No one else has asked me. I’m available.”

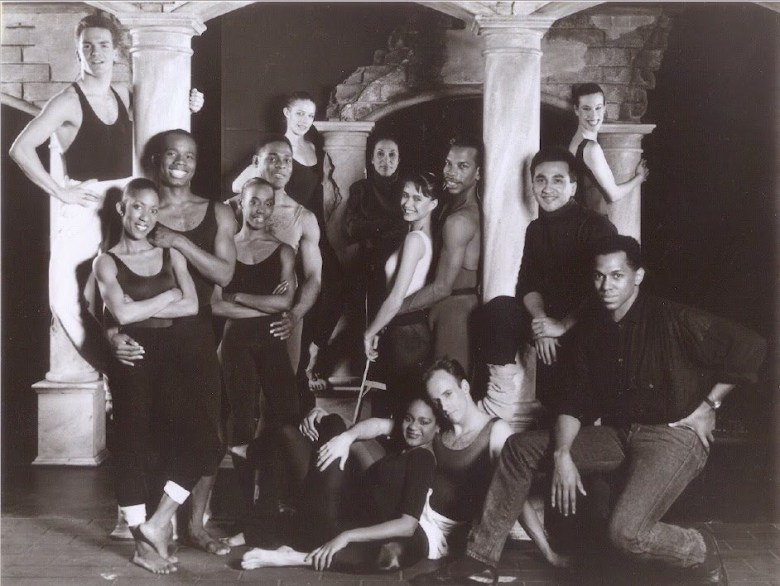

The company of Joseph Holmes Chicago Dance Theatre, year unknown. On floor in front, L-R: Kim Gadlin and Keith Elliott (cofounder of Dance for Life). Seated on far right, hand on hip, is Randy Duncan. Standing L-R: Robyn Davis, Byron Jones, Cynthia Bowen, Kevin Ware (arm around Cynthia), Pam Jankelow, Roger Turner, Cuitlahuac Suarez. Left pillar: Patrick Mullaney; center pillar: Ariane Dolan, right pillar: Winifred Haun. Harriet Ross is center rear in dark clothing. Credit: Jennifer Girard

The company of Joseph Holmes Chicago Dance Theatre, year unknown. On floor in front, L-R: Kim Gadlin and Keith Elliott (cofounder of Dance for Life). Seated on far right, hand on hip, is Randy Duncan. Standing L-R: Robyn Davis, Byron Jones, Cynthia Bowen, Kevin Ware (arm around Cynthia), Pam Jankelow, Roger Turner, Cuitlahuac Suarez. Left pillar: Patrick Mullaney; center pillar: Ariane Dolan, right pillar: Winifred Haun. Harriet Ross is center rear in dark clothing. Credit: Jennifer Girard

I taught class, and at the end of class, he said, “We’d like you to train the company.”

In 1995, Jerry Arpino called and said he was coming into Chicago, and he’d like to meet with me. I knew him. I took one of his ballet classes and then cried for two hours after. So I never went and took another.

I was general manager. I wasn’t general manager to start with, because I told Jerry that I didn’t want to work full-time for him. I was coaching some companies, and I was teaching, and I loved all these things. He said, “But I needed you on Tuesday.” I said, “Jerry, I cannot leave a job I’ve elected to do. I’ll go on a leave of absence after the semester’s over, and then I will work for you as you need me”—which turned out to be 24/7.

In 2000, Yuriko came to set Appalachian Spring on the Joffrey. It was an explosive time. It was after Graham’s death, and Ron Protas was left everything. The ending of the court case wasn’t until after we presented Appalachian Spring. Ron was being represented by a major touring agent, and they wanted $30,000 for Appalachian Spring, paid upfront.

Jerry was very excited about it. He very much wanted Appalachian Spring to happen—so we paid up—and not at a time where we had very much money. We just loved working with Yuriko. She had this gift of making everybody cry during rehearsal. Willy Shives, I will swear, walked out of every rehearsal crying because he had been so touched by everything she did. And that was true of almost everybody. It was so uplifting, the time spent with her.

At some point, Martha Graham was quoted as saying, “My work will die with me.” Now if that was her desire, Ron was the right person. I do believe in an artist’s rights.

The works are wonderful. It’s a wonderful company. The works will live.

Reader Recommends: THEATER & DANCE

Reader reviews of Chicago theater, dance, comedy, and performance arts.

Nahal Navidar’s thoughtful and moving one-act finds a home with Momentary Theatre.

January 12, 2026January 15, 2026

Actors and improvisers come together to create a long-form show inspired by existing scripts.

January 7, 2026January 7, 2026

The musical’s awash in nostalgia, but sometimes you’ve gotta give ’em hope.

December 22, 2025December 22, 2025

Madie Doppelt’s The Model Play takes a sharp look at young women in the fashion industry.

December 17, 2025December 17, 2025

Going behind the scenes with The Not That Late Show

December 16, 2025December 16, 2025

Celebrating the season with ʼTwas the Night Before . . . and Cirque du Soleil

December 16, 2025December 16, 2025