Dallas County District Court Judge Vonda Bailey has sued county Commissioner John Wiley Price for defamation, alleging he launched a “campaign to damage her credibility and reputation” after she did not reciprocate his personal advances.

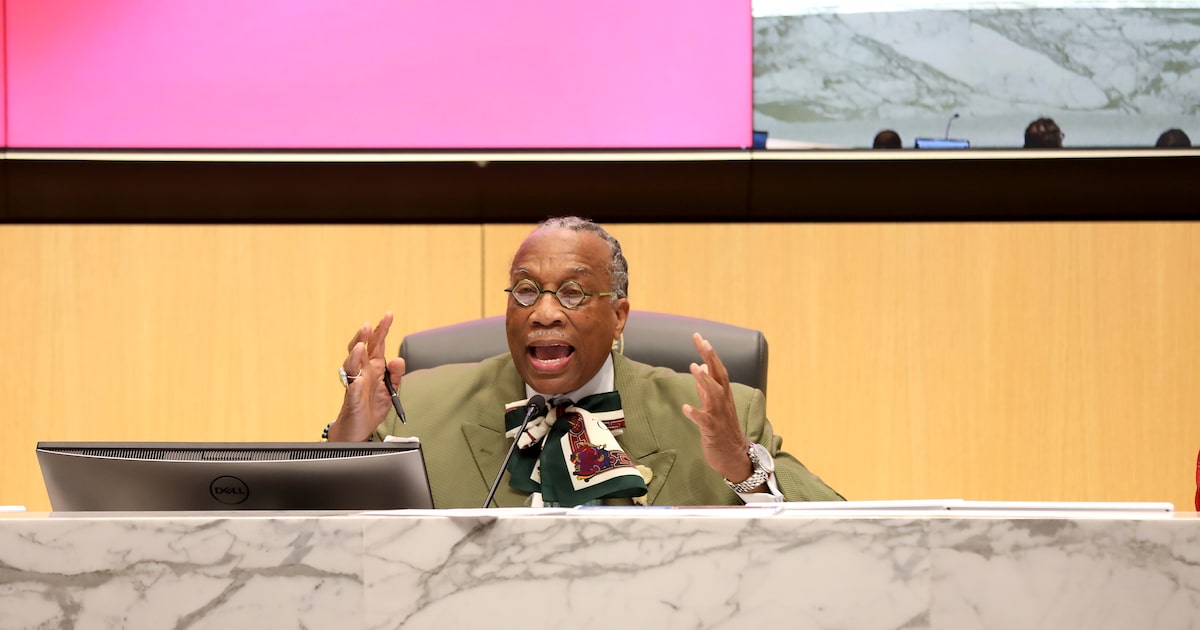

Price, who has served as a commissioner for 40 years, did not immediately respond to a call, text message or email requesting comment on the lawsuit.

In multiple Commissioners Court meetings since September, Price questioned Bailey’s productivity while displaying her social media posts, including an Instagram video in which she gave hair care tips while in her robe in the courtroom.

While online judicial records report Bailey’s case clearance rate to be near 100%, Price announced in Commissioners Court he calculated it at 28%, alleging she falsified data, according to her complaint.

Political Points

“The implication was clear, he wanted to paint Judge Bailey as a person stealing county time and resources,” the complaint states. “He presented no documents, statistics or records to support his allegations of misconduct.”

The lawsuit, filed Wednesday in Dallas County district court by Houston attorney Peter Clarke, alleges community members and one local news outlet repeated Price’s comments about her clearance rate that he knew were false, impugning her integrity as a judge.

Dallas County 255th District Court Judge Vonda Bailey

Dallas County / Dallas County

State law affords elected officials immunity from liability while acting within their authority. Bailey alleges Price is not protected by such privilege because his comments were made outside the scope of legislative activity and were unrelated to any pending county business.

When Bailey first ran for the 255th district court in 2022, the lawsuit alleges Price contributed to her campaign and “attempted to cultivate an appearance of political guidance.” Both are Democrats.

“He stopped by her chambers frequently, bringing lunches and offering unsolicited mentorship,” according to the lawsuit.

According to the complaint, when Bailey did not reciprocate these overtures, Price’s demeanor shifted and he began “a sustained and targeted” campaign to damage her reputation.

During an October Commissioners Court meeting, Price displayed a Facebook post by Bailey and said she had been absent from work for 131 days “by her own admission.”

“You got good judges over there coming to work every day, working hard, and then you got other judges out there playing and posting,” Price said.

In the Oct. 6 post partially pictured in her lawsuit filing, Bailey stated she had been studying for a board exam “for the past 131 days (May 27th through October 5), taking off only 14 non-consecutive days in between.”

Bailey’s lawsuit states she did not take a hiatus from the bench and Price mischaracterized days she spent studying as days she wasn’t working.

Not shown in the filing, the post continued: “I specifically set my court docket to ensure I didn’t have any cases scheduled during this time except for those with statutory deadlines (CPS cases, Motions for New Trial).”

Online judicial records show Bailey had 1,031 cases added and 1,140 disposed during that four-month period where she was studying for the exam. That is below the 1,402 cases added and 1,339 disposed in the four months prior, records show.

In a statement, Clarke, her attorney, said judges are not county employees and the state does not mandate a judge to work from inside the courthouse. He said the work schedule is based on the docket.