1. The Many Hands That Built the West

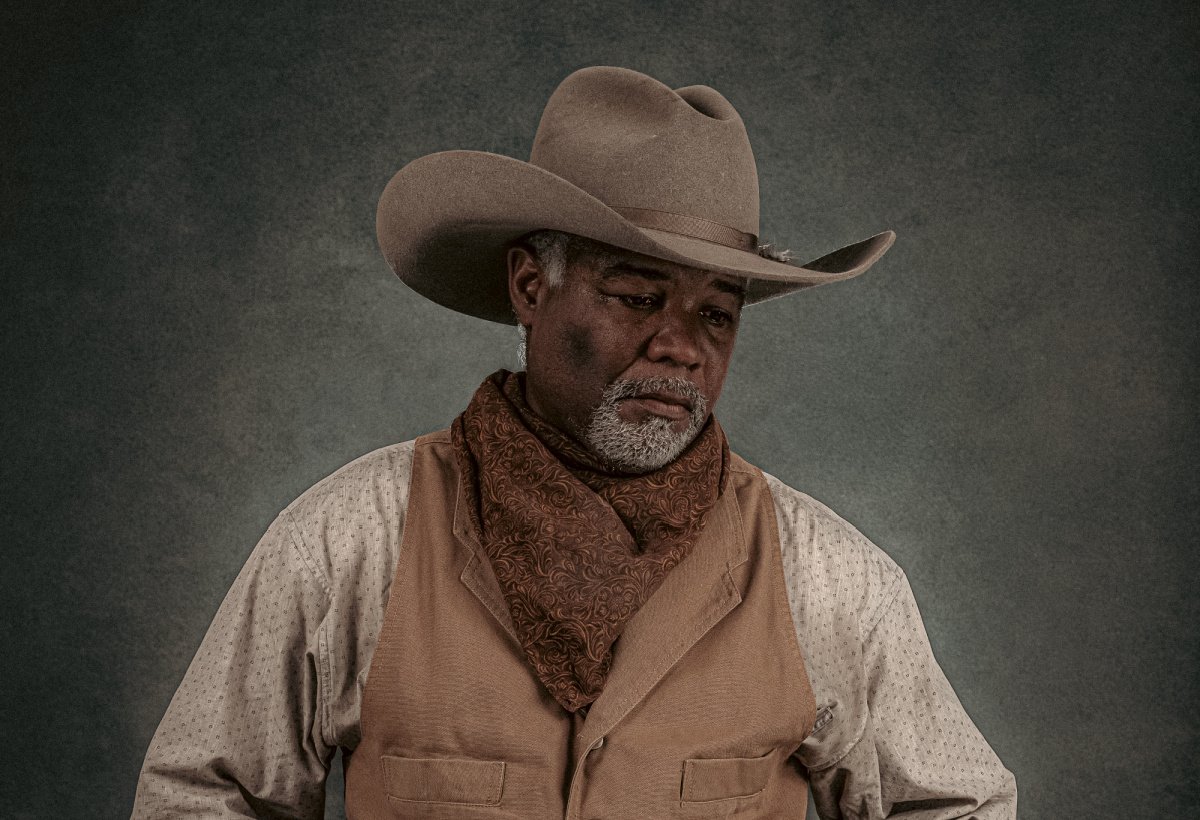

It’s Nov. 16, 1907, and the vast, rich landscape Bass Reeves had patrolled for 32 years as a deputy U.S. Marshal has officially become the 46th state in the Union. No longer Indian Territory and now Oklahoma, the land’s transition to statehood ushers in the retirement of the 68-year-old Reeves. The fabled lawman’s decision to holster his revolvers and turn in his badge brings about a collective sigh of relief from criminals, fugitives, and outlaws who have dared cross into Indian Territory — the men whose nightmares Reeves had haunted.

Over a decade before he became a U.S. Marshal, during the Civil War, Reeves had escaped slavery in Texas — killing his slaveowner over a poker game, as legend has it — and sought refuge in the Indian Territory, where he would live with and learn from the indigenous tribes. During his three-decade tenure as a U.S. Marshal, Reeves made a nearly unthinkable 3,000 arrests and killed 14 outlaws (all in self-defense, mind you). All the more remarkably, according to historian and Bass Reeves biographer Art T. Burton, Reeves emerged unscathed, with hardly a scratch on him, from every encounter with the territory’s most-wanted and depraved. His garments, however, were not as fortunate, as both hats and belts famously fell victim to perforation from gunshots — a life of near-misses.The exploits and good deeds attributed to Reeves can seem so outlandish and sound so improbable that one would naturally question whether the stories are of myth or legend. Fearless, formidable, principled, and incorruptible, Reeves is the greatest real-life hero the Wild West ever had — the King Arthur and Hercules of saloons and shootouts.

Whether tall tales or faithful accounts, following Reeves’ death, it would take 113 years for his story to reach a wider audience, which it finally did thanks to the Taylor Sheridan-produced series “Lawmen: Bass Reeves.”

Wyatt Earp, Pat Garrett, Bat Masterson, and even anti-heroes like Jesse James and Butch Cassidy, meanwhile, got their stories told through the entire evolution of media — pulp novels, radio programs, cinema, and television sets — with wearying frequency. There was, however, one fictional character whose life and acts of daring seem to mirror that of Reeves: the Lone Ranger.

“How does the Black Lone Ranger turn White?” wonders Donald Lee, a 15-year veteran of the Fort Worth Herd. “I mean, I grew up watching Randolph Scott. I grew up watching Clint Eastwood, John Wayne, all that, right? And that’s really cool. But as a Black kid, it’s also important to see [someone who looks like you] on a big screen.”

Despite the historically unceasing popularity of men carrying six shooters and riding horses in movies and TV shows, from the silent-film era to talkies and technicolor, in Hollywood, Reeves was largely forgotten.

“Black cowboys, Hispanic cowboys — they were an integral part of shaping the West,” Wendell Hearn of the Cowboys of Color Rodeo says. “But when Hollywood made the pictures, we just somehow got left out.”

Whatever the reasons may be — racism, whitewashing, economics — Reeves is merely one example of this exclusion. If films were to strive for authenticity and portray the West accurately, their casts would be so diverse and representative that it would fundamentally reshape our familiar image of the American West. “Even now,” Lee says, “when Black people come to the Fort Worth Stockyards, and they see me, it’s like I’m a unicorn.”

According to some estimates — many of which happen to be reputable — during the romanticized post-Civil War cattle drives from the 1860s to the 1880s, nearly half of cowboys were either Black or Hispanic.

“Many of the events people see in rodeos are based on things that were once jobs [on cattle drives],” Jarred Howard, owner and operator of 2REquine says. “And the job wasn’t something that’s pretty. Wrangling 1,200-pound cows in harsh weather and traveling miles and miles in blazing heat and blasting cold — that was not desirable. But people need to know that a large percentage of the people doing it were [people of color]. I think it’s important for people to know that history.”

Despite what we may see on the small or silver screens, where John Wayne leads the herd and gets the girl, bearing witness to a real cattle drive of the 19th century would be difficult to romanticize. The obstacles — weather, terrain, animals, disease, and Indigenous resistance — were endless and claimed many lives. And the physical hardships (for man and horse) — never-ending saddle bruises, dehydration, muscles strains, and hoof injuries — weren’t inconveniences but constants. Those who managed to adapt to the trail life were some of the most physically and mentally hardened people of that era. Complain about a rock in your boot, and someone’s likely to give you something far worse to complain about.

“The cattle drive and ranching, they’re not a glamorous job,” Hearn says. “So, you really didn’t care what the other guy looked like as long as he could do the job. I mean, there weren’t a lot of people looking to do the job, so if you found someone who wanted to do it and could do it, it didn’t matter what skin color he was.”

If one is interested in witnessing a more accurate representation of a 19th century trek by horse, Fort Worthians don’t have to look much beyond their own backyards. With Black and Hispanic drovers in their ranks, including long-time vets like Lee and Jose Hernandez — a vaquero from Del Rio who makes his own chaps — the Fort Worth Herd includes a diverse representation more accurate than anything one might read in books by Louis L’Amour or see on shows starring James Arness. But those who embark on the twice-daily cattle drives down East Exchange Avenue — the professional drovers who have had more eyes on them than any cowhand in the past — know their purpose goes far beyond trying to achieve an accurate portrayal of a 19th-century cattle drive.

“I’m very proud to represent my culture and, like they say, mi raza [my race],” Hernandez says. “And especially [in The Herd] because I want to be able to continue to [practice the vaquero culture] and inspire the new generation. I’m always willing to help anybody who wants to learn and tell them my story.”

“Every kid deserves to be able to see something positive about their race projected in a positive way,” Lee says. “And oftentimes, especially the era we grew up in, there wasn’t a whole lot of positive — unless you want to talk about pro football and stuff like that. But in terms actually contributing to the building of a nation or to the revitalization of the economy of a particular state, we don’t see much about it. And that’s huge! [what Black cowboys accomplished] should make us feel proud.”

Without the cowboys who did the dirty work to lay the foundation in the West — to help make life a little less difficult for others — the sprawling new frontier that epitomized hope and the American Dream, would have never existed.

The West was built by many hands, and it’s time we remember them.

2. The First Cowboy

One might assume that to definitively proclaim any one race or culture as the first to “cowboy” is risky business. Give the incorrect answer, and your response could be bordering on blasphemy. However, the true first cowboy — those who first served as cowhands — in this case, isn’t debated, but it is a complex tale rooted in colonialism and classism.

According to “The Original Cowboys” by Katie Gutierrez for Texas Highways, cowboys first appeared south of our current border in what was then the Spanish frontier (Mexico) in the 16th century — not terribly long after Cortés conquered the Aztec Empire and over 100 years before the idea of a United States of America had even surfaced.

Upon arriving during his first expedition, Hernan Cortes brought 16 horses, effectively introducing the statuesque species to the area and giving the Spaniards a clear advantage in battle. Following his conquest and wishing to keep the horse a benefit for the few, Cortes ordered that a Native American riding any equine was punishable by death. But this policy would become a hindrance once the expanding livestock required horsemen to do labor the conquistadors felt was beneath their status. Unwilling to give the task to the Indigenous people, the Spanish assigned this new job of wrangling and caring for the cattle to their Moorish slaves, whom the conquistadors would go on to disparagingly refer to as vaqueros (directly translating to “cow-men”). So, these enslaved Black Muslim men were effectively the first cowboys.

Soon requiring more vaqueros to assist in working cattle, the Spanish would drop their previous ordinance that came with a death sentence and began allowing the Indigenous people to ride horses. Except, they could only do so without a saddle, as such luxuries for the derriere “were the mark of gentlemen.” According to Gutierrez, forcing the Indigenous to go saddleless means the Spanish “unwittingly ensured that Native Americans became superior horsemen.”

Fast-forward 100 years, and the descendants of the Spanish, Native Americans, and Moors produced the first generation of Mexican vaqueros. Raised with a Spanish method of catching small game using ropes from native fibers, they would go on to work cattle using similar methods with lassos made from cowhide.

Driving herds of cattle, the vaqueros quickly adopted new clothing and techniques to make their work and lives easier, resulting in the advent of sombreros, chaps, and lariats. Competitions would soon emerge from these new-found methods, producing roping, reining, bronc busting, and bull riding. In short, the vaqueros gave the Anglo settlers their first lessons in being cowboys and even gave them their first appetite for rodeo. With a three-century head start on their White counterparts, vaqueros spent generations learning, working, and honing their craft, forging a distinct, familial, and deeply proud culture.

Also receiving cowhand tutorials from vaqueros were newly emancipated Black men and women who headed west, particularly to Kansas, seeking economic opportunity in the midst of reconstruction. Learning the skills of the vaquero, Black cowboys were able to acquire jobs as ranch hands, trail hands, and horse wranglers from which they typically made equal wages to their White counterparts.

“[Black cowboys] occupied all the positions among cattle-industry employees,” Kenneth Porter writes in African Americans in the Cattle Industry, “from the usually lowly wrangler through ordinary hand to top hand and lofty cook.” That said, Porter reminds us that post-Civil War, inequality remained rampant west of the Mississippi. “But [Black cowboys were rarely] found as ranch or trail boss,” he continues. “And were typically assigned to handle [break] horses with poor temperaments and wild behaviors.”

It’s not as if this world of bovines, barns, and broncs was completely foreign to these cowboys, either. According to Tracy Owens Patton in Let’s Go, Let’s Show, Let’s Rodeo: African Americans and the History of Rodeo, enslaved men and women in the South would regularly manage large herds of cattle. In these instances, ranchers would distinguish White ranch hands from Black ranch hands by calling them “cowhands” and the more pejorative “cowboys,” respectively. And not long after the American Revolution, these cowboys would regularly partake in competitions related to their cowhand skills — competitions from which their White owners would profit.

Sounds an awful lot like the first cowboys in a rodeo.

Regardless of whether these events or those cowboys ever receive such a distinction, some semblance of the rodeo we know today did kick off a century later thanks to the traveling vaudeville acts of Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Shows. And two of the sport’s biggest acts entering the 20th century were Black cowboys — Bill Pickett, who invented the sport of bulldogging, and Jesse Stahl, widely regarded as one of the greatest saddle bronc riders of all time.

Setting up shop within The 101 Ranch Wild West Show near Ponca City, Oklahoma, Pickett showed thousands of curious onlookers his new sport inspired by the method dogs use to subdue cattle: biting their upper lip. The sport had Pickett, saddled atop a horse, chase a steer in full gallop. He’d then leap from his horse, grab the steer by its horns, and wrestle it to the ground often by biting its upper lip. Though a novelty act in 1910, today, the sport is known as steer wrestling, and it’s now one of the nine events that make up ProRodeo competitions. And it’s also the only event whose invention can be traced back to a single person.

3. Quanah Parker and the World’s Greatest Horsemen

Lance Tahmahkera talks about the two horses he feeds every morning. “They’re our pets,” he says, waving off any seriousness about his riding ability. When speaking about himself, Tahmahkera drizzles everything with a thick coat of humility. But bring up his tribe, his people, his legacy — in other words, add the element of the Comanche — and his voice becomes sharp and assured.

“The Comanche were the greatest horsemen in the world,” Tahmahkera says, shifting to a matter-of-fact tone. He’s not gloating or beaming with a brazen amount of pride, either. Tahmahkera simply understands his culture and takes pride in the lineage, histories, and traditions of those who came before him. And the Comanche, for the sake of survival and preserving their culture, rode horses as if man and equine shared a single nervous system.

Tahmahkera is a great-great-grandson of Quanah Parker, the last chief of the Kwahadi Comanche and first-born son of Cynthia Ann Parker, whom the Comanche had kidnapped at the age of 9 following a raid on Fort Parker. The story of Cynthia Ann and Quanah is one that’s cinematic in scope and continues to draw interest, stir thoughts, and raise questions. And it’s a story Tahmahkera is used to telling. After all, he tells it pretty regularly at schools, libraries, and lecture halls despite being an introvert. “If I keep my word count to 100 a day, I’ve had a good day,” he says. “But if it’s about the Comanche people, I can talk endlessly.”

Tahmahkera begins his story with the Comanche themselves. It’s generally agreed the Comanche were a spinoff of the Shoshone, originating farther north — in Wisconsin — before moving south and becoming a people of the plains. There are multiple oral explanations for why — buffalo, sickness, and a legendary dispute between families — but no one can be certain. Regardless, the Comanche, following the buffalo across a vast range that included West Texas, Oklahoma, and beyond, became nomadic. And the advantage that set them apart from other plains tribes was the horse.

“We learned how to hunt and how to fight from the back of a horse,” Tahmahkera says. “That’s what made us the most dominant tribe in that whole area.” To the Comanche, the horse wasn’t simply transportation, it was integral to their survival, culture, and way of life; these horses, with a specific gait and stamina, were bred and shaped for the Comanche.

In 1836, the Comanche home of Texas found itself in the crosshairs of a growing number of new settlers and in a struggle for independence — for Texas to become a slave-owning nation unto itself. Among these new settlers were the Parkers, who arrived from Illinois in the mid-1830s and built Fort Parker in present-day Limestone County, just east of Waco, to preach Christianity to local tribes. Yet, according to Tahmahkera, their underlying purpose was to unknowingly serve as a territorial line for Mexican interests. “Mexico still controlled Texas, and Santa Ana was giving away land,” Tahmahkera says. “They were using settlers as a buffer to keep the Comanches and the other tribes from going further into Mexico.”

On May 19, 1836 — one month after Texas’ victory at San Jacinto and the Alamo still fresh in memory — a large raiding party of about 300 Comanches arrived at Fort Parker under the pretense that they sought water. According to Tahmahkera, the raid ended with five settlers killed and five captives taken, one being a 9-year-old Cynthia Ann.

Captivity, Tahmahkera explains, was part of the brutal frontier reality — one that included bargaining. “We stole people,” he says. “The women we took, you could use them as slaves. You could literally barter them back.” But children were taken, too, and Cynthia Ann became the most famous example — vanishing from the Anglo world for 24 years.

During that time, she was raised as a Comanche — seen as no different from anyone else in the tribe — and would go on to wed and bear the three children of Peta Nocona, the tribe’s chief. Of their three children, Quanah, which means “golden eagle”, was the eldest.

By all accounts happy with her life among the Comanche people, Texas Rangers would recapture Cynthia Ann during an attack along the Pease River. The incursion, led by Sul Ross, occurred when the Comanche men were away hunting, so Cynthia Ann was taken along with her daughter, Topsannah [meaning “prairie flower”]. Word was then sent to Cynthia’s uncle who lived in Birdville — his home sitting on the land that’s now occupied by the North East Mall in Hurst. However, Cynthia Ann did not return to Anglo life as a restored daughter or niece, she returned as a woman separated from her family, unable to speak her natural tongue, and grieving for the two children and husband she would never see again.

With her aunt and uncle too old to care for her, Cynthia Ann would end up in East Texas to live with her brother, Silas Jr.

“She did assimilate back into the White person way of life in East Texas,” Tahmahkera says. “She did OK, but then Topsannah, her daughter, got ill and died just a couple of years later.

“Cynthia [Ann] just gave up after that. She didn’t know what happened to her family, her husband, her other two children. And the story I’m told, the story my family tells, she basically starved herself to death. Her heart was broken.”

Tahmahkera recalls a story from his father’s aunt — a woman who carried firsthand family stories through Quanah’s household. As a child, she asked one of Quanah’s wives whether the Comanche truly accepted Cynthia Ann — a stolen, blond hair, blue-eyed, white-skinned girl. Her response: “She was Comanche all the way.”

That distinction matters in a culture that has long been filtered through Hollywood, bestselling historical fact and fiction, and general appropriation. Tahmahkera laments about the stories in mass circulation bent for profit. And his family, particularly his great-great-grandfather, Quanah Parker, has been on the receiving end of these fallacies.

“It sells the books, but it destroys a legacy.”

Following his father’s death in 1864, Quanah became a prominent warrior and helmsman among the Comanche people, famously refusing to sign a treaty with the U.S. government in 1867. And for the next eight years, Quanah and the Kwahadi people would continue to fight those encroaching on their land, their resources (the bison), and their traditions. In 1874, tensions would escalate into the Red River War, a military campaign to forcibly relocate the remaining free tribes onto reservations in Indian Territory.

After Col. Ranald S. Mackenzie, the man tasked with subduing the plains tribes, managed to round up and slaughter over 1,000 of the Kwahadi’s ponies, it became impossible for the tribe to continue fighting. “They killed those horses knowing that we could no longer fight,” Tahmahkera says. “I mean, that was our way of life, the horse. And it was the next summer when Quanah led the Kwahadis onto the Fort Sill Reservation.”

The Kwahadis were the last tribe to surrender.

According to Tahmahkera, Quanah was a leader under impossible terms — a man born into a world of buffalo and war who guided his people through surrender, reservation life, and forced assimilation without losing their identity.

Upon entering Fort Sill, the first question Quanah asked was simple: “What happened to my family? My mother, my sister. What happened?” Following the surrender, Quanah would visit his mother’s side of the family in East Texas, learn English, and take the name Parker to honor his mother.

With new insights and a keen understanding of the expanding White culture, Quanah would negotiate the survival of his people in a new economy. Now on a reservation in Indian Territory, Quanah would become a successful rancher and investor, gaining a considerable amount of wealth that he regularly shared with his people. A shrewd businessman, he only allowed cattle from other ranches to pass through Comanche land for a fee. If ranchers refused, they were forced to go around. Tahmahkera says this was a lesson Quanah once taught the famous Charles Goodnight, a rancher of unusual renown. After Goodnight refused to pay the toll and trekked the additional miles to go around, he paid the next time he entered Comanche land.

Quanah, whose statue now sits in the Stockyards, would visit Fort Worth often on business trips and, in 1909, would lead 38 members of his tribe in full regalia during the Stock Show & Rodeo parade. Quanah would also travel to Washington, D.C. and became friendly with Teddy Roosevelt — riding in his inaugural parade and hosting the president during a 1905 wolf hunt.

Fathering 25 children, one can find descendants of Quanah’s far outside the Comanche Nation near Lawton, Oklahoma. But Fort Worth, a city Quanah once frequented, has become an unexpected anchor for the Comanche warrior’s legacy. After serving in World War II, Quanah’s grandson, Vance Tahmahkera, moved to Fort Worth where he worked at the U.S. Postal Service for 23 years and raised his family. Vance’s brother and Lance’s father, Monroe, would soon follow, working at Carswell Air Force Base, where he did air conditioning and heat installation for 50 years.

Despite Quanah’s assimilation, Tahmahkera continues to circle a defining principle: adaptation without erasure. “Quanah said two things,” Tahmahkera tells me. “He said, ‘Learn the white man’s ways. Keep our Comanche culture.’”

Tahmahkera worries about lost language, lost stories, lost traditions, and lost legacies. According to Tahmahkera, about 1% to 2% of the 17,000 Comanches can fluently speak Comanche. But an effort is underway, including the founding of a committee and school dedicated to the survival of the language, to keep it alive.

But there is something else, a defining aspct of the Comanche culture that’s almost amorphous — their unparalleled horsemanship, measured wisdom, and deep knowledge of the plains — that are also worth honoring and carrying forward.

“I am just one person,” Tahmahkera says regarding his efforts at preserving the Comanche way of life. “I’m but a drop in the bucket. Our culture’s not going to get lost, but we have to be vigilant to make sure that that doesn’t happen.

From his gym bag full of Comanche artifacts, Tahmahkera takes out an eagle’s feather — a possession very much earned in Comanche culture— and explains that each barb on the feather represents “every little incident that happens in my lifetime that makes me up as a Comanche. And the stem running through the center ties it all together. That’s my life as a Comanche you’re holding.”

And it’s a life, lineage, and culture he will continue to share. “I have a great honor of being a Comanche,” Tahmahkera says. “But it’s also an obligation. You can’t just let it die with you.”

4. A Heritage on Horseback

In the morning hours of Saturday, Jan. 17, horses outnumber cars on the streets of downtown Fort Worth. Without a combustion engine within earshot, thousands of cowboys and cowgirls guide their steeds along the brick roads near Sundance Square, tracing the route of the annual “All Western” Parade, which officially kicks off the Fort Worth Stock Show and Rodeo. For a couple of hours, these high-traffic thoroughfares revert to their storied past, resembling something closer to a stockyard than a downtown.

Making their way through a tide of denim and beaver felt cowboy hats are the colorful dresses and ornate sombreros worn by the escaramuza. And beside them is their male counterparts, the charros, who will also be performing during the Best of Mexico Celebracion taking place the following day inside Dickies Arena.

During previous years, this distinct part of the Stock Show and Rodeo, a charrería, which is the national sport of Mexico, was normally relegated to an early morning time slot in the Will Rogers Coliseum. Today, the dazzling pageantry of escaramuza, an incredible showcase of precision and control over one’s equine partner, combined with the valor and virility of the charro, has made the Best of Mexico Celebracion a popular go-to event that offers a respite from the normal rodeo fare. That said, folks still get their fill of bull riding and bronc busting from sombrero-clad charros.

After the charros and escaramuza pass during the “All Western” parade, another group of riders appear, proudly flying black flags emblazoned with “Circle L 5 Riding Club” — the first and largest Black riding club in Fort Worth with over 100 members in its ranks. No single riding club represented in this parade fought harder or longer for inclusion after they were sidelined in the 1950s due to segregation.

“We do a lot of community outreach,” says Jarred Howard, owner of 2REquine and longtime member of Circle L 5 Riding Club. “We do a lot of supporting and uplifting the culture of the Black cowboy, and we do our best to maintain that culture and give younger generations and older generations an avenue to continue to develop and to engulf themselves in the culture.”

The Circle L 5 Riding Club will also take part in the Cowboys of Color Rodeo, which has taken place on Martin Luther King Jr. Day at each Stock Show & Rodeo since 2010 — the multi-date rodeo has been around since 1971, when it was founded by Cleo Hearn as the Black American Rodeo. Dedicated to showcasing and paying tribute to the forgotten side of Western history and culture, the rodeo spotlights cowboys and cowgirls of Black, Hispanic, and Indigenous heritage.

This will mark the first year the multicultural event will take place without its founder in attendance, as the Western world continues to mourn the loss of Cleo, who died in November 2025. Though the pluralistic rodeo pioneer and champion roper created the event to teach history and spotlight other cowboys of color, Cleo, himself, has an incredible story full of historic accomplishments that go beyond the creation of the Cowboys of Color Rodeo, including serving on President John F. Kennedy’s presidential honor guard and becoming the first African American to attend college on a rodeo scholarship. Cleo’s four sons, Harlan, Eldon, Robby, and Wendell stepped in over the past few years to continue the tradition and become equal leaders of the annual event, which, like the Best of Mexico Celebracion, has seen an uptick in interest and attendance over the past few years.

According to Wellen, the success is the result of his father’s dogged determination.

“It’s incredible to witness the success because we also witnessed what he did to build it — the hard times when he was first trying to put [the rodeos] on and couldn’t get much traction,” Wellen says. But, as he emphasizes, they need to strike while the branding iron is hot.

“The stories and culture [of the forgotten cowboys] needs to carry on because, as quickly as it’s become popular, it can disappear just as easily if you don’t keep the ball rolling. And we don’t want it to disappear again.”

With such incredible, rich, and story-filled histories, the legacy of the true cowboys of color could seem like a lot to live up to. And, well, it is.

After all, the likes of Bass Reeves, Bill Pickett, Quanah Parker, and Simón de Arocha didn’t just contend with heat, dust, stray bullets, and rattlesnakes, they also navigated an immense amount of discrimination, demonstrated by their overlooked history, to help shape and forge the mythology of the vast land west of the Mississippi.

But these contemporary representatives of the culture know they’re putting their boots in stirrups for reasons that far outweigh any pressure or expectations they may feel.

Donald Lee tells a story about an uplifting moment that happened when doing a program with the Fort Worth Herd — the kind they regularly do for curious visitors to the Stockyards. “It wasn’t yet my turn to talk, but I’m in the arena with the other drovers and we were all taking turns doing our presentation. There was this one Black boy, he must have been about 10. He stayed looking at me. He stayed looking at me no matter what was going on.

“And then when it was my turn to talk, his eyes just lit up. And afterward, they wanted to take a picture with me, and this little boy gave me the biggest hug — he was so excited. [And I can’t help but think] when he looked at me, he saw himself doing something positive.”