STATEN ISLAND, N.Y. — A recently-published history of a small slice of Staten Island offers a glimpse at local changes and some of the borough’s place in the nation’s history.

College of Staten Island professor and archivist Dr. James Kaser wrote the study of the Island’s Elliottville, congruous with part of modern-day Livingston around Bard Avenue, and said the history may be of interest to Staten Islanders given its local ties to the American story.

The book focuses on a small Staten Island community and the people who comprised it, including several prominent abolitionists in the lead up to the American Civil War.

“This is a part of Staten Island history that makes Staten Island nationally prominent,” the author said. “I think in general, many Staten Islanders know that abolitionists lived on Staten Island, but I don’t think that they understand how important those abolitionists were in the abolitionist movement. I also don’t think they understand how important those people were in a range of social reform movements.”

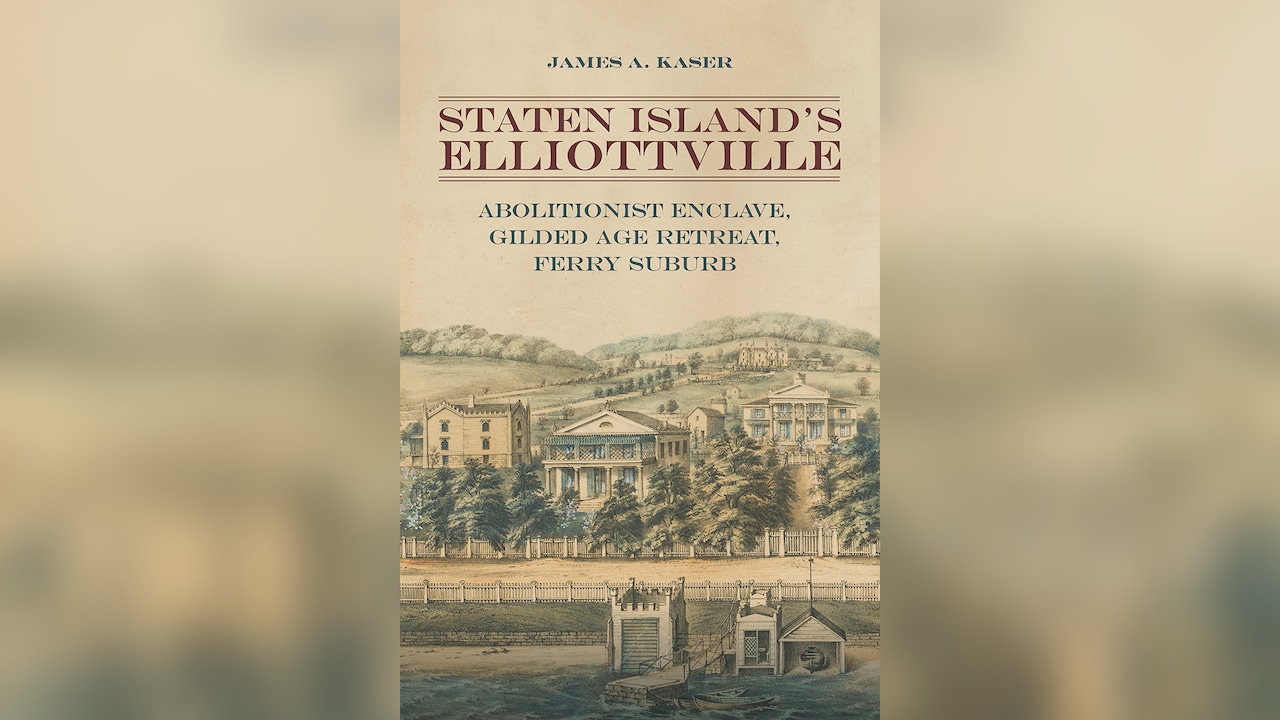

College of Staten Island Archivist Dr. James Kaser history of Staten Island’s Elliotville neighborhood explores the small slice of Staten Island’s place in the nation’s development.(Courtesy: SUNY Press)

College of Staten Island Archivist Dr. James Kaser history of Staten Island’s Elliotville neighborhood explores the small slice of Staten Island’s place in the nation’s development.(Courtesy: SUNY Press)

Kaser’s work explores different aspects and several eras of the small neighborhood named for Dr. Samuel McKenzie Elliott.

A native of Scotland, Elliott was a medical doctor who pioneered ophthalmology in the United States and built the community around modern Bard Avenue largely as a recovery community for his patients.

Elliott purchased land for his community from the Bard family, who disputed references to the area as Elliottville and have ultimately seen their surname have a longer lifespan in the neighborhood.

Today, the modern Staten Island neighborhood of Livingston has subsumed most of what was Elliottville with only a single home on Delafield Place still standing.

Richard Carlin, an acquisitions editor for SUNY Press, which published Kaser’s book last year, said the work helps to tell the story of Staten Island.

“We thought this was an important and little-known story that deserved to be told,” he said. “The author has done landmark research on the topic, and we believe it illuminates the history of how Staten Island and how this community was built by its unique combination of inhabitants.”

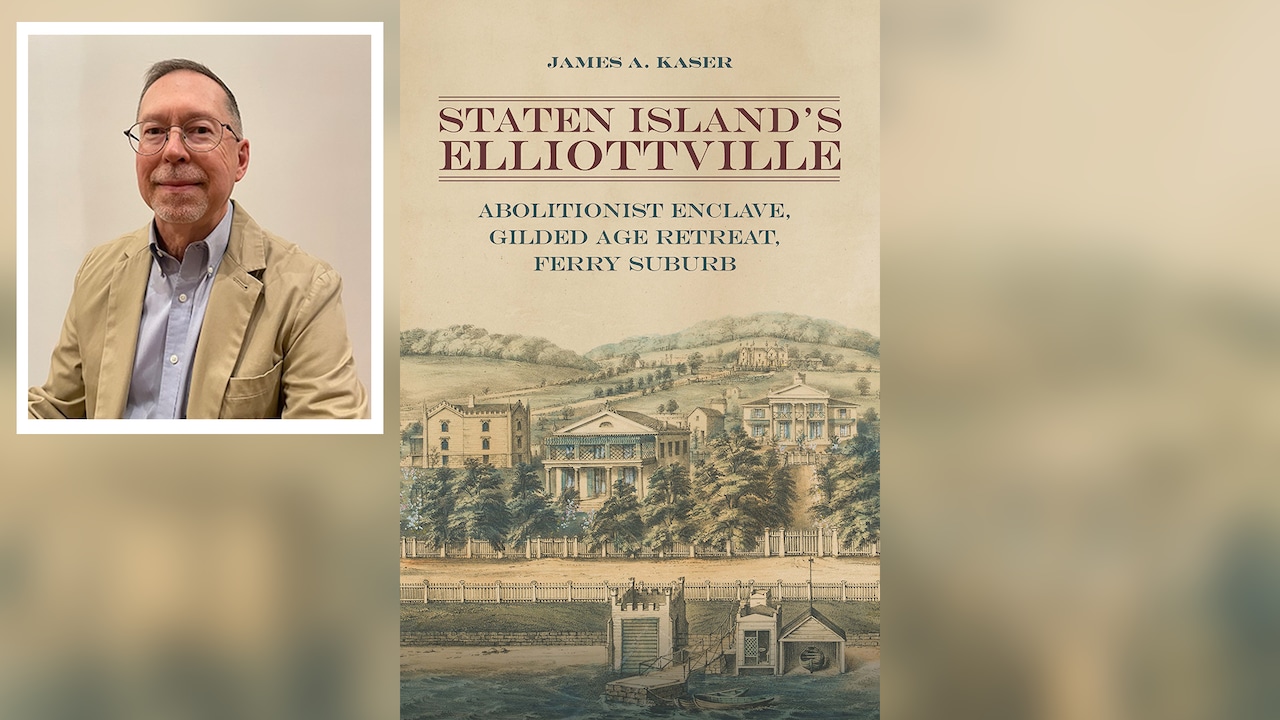

College of Staten Island professor and archivist, Dr. James Kaser, recently published a story exploring the history of a small slice of Staten Island.(Courtesy: Dr. James Kaser)

College of Staten Island professor and archivist, Dr. James Kaser, recently published a story exploring the history of a small slice of Staten Island.(Courtesy: Dr. James Kaser)

The early part of the book explores Elliott’s personal commitment to the abolition of slavery, including service in the Civil War, and his community’s attraction of a number of prominent abolitionists of the pre-war era.

People like George W. Curtis, the St. George high school’s namesake; abolitionist Sydney Howard Gay; and Civil War hero Robert Gould Shaw counted themselves as residents of Elliottville.

Elliott’s work as an oculist, an early term for an eye doctor, and his advocacy for holistic treatment helped attract many of the progressive-minded people with New England ties to his North Shore community, which at the time was served by a Manhattan ferry at the foot of Bard Avenue.

Elliott built the homes in a specific way that contributed to a way of life referred to throughout the book as “living cottagely.”

Their abolitionist views put the residents of Elliottville at odds with many of their contemporary New Yorkers, particularly on Staten Island. One Gay family story retold in the book laments Elizabeth Gay’s run-in with a group of bigots on a ferry ride back from Manhattan.

Harriet Forten Purvis, a prominent Black abolitionist and suffragist of the era, accompanied Elizabeth, the wife of Sydney Gay, on the ferry ride during which a bold racist called her the n-word.

The book closes with an exploration of Erastus Wiman’s late-19th-century railroad efforts around the Island challenged by the people remaining in Elliottville.

A villain of Staten Island history in Kaser’s view, Wiman’s work included the construction of the Staten Island Railway’s North Shore Branch, partially along the waterfront, and the consolidation of Staten Island ferry service at the St. George Terminal.

“It helps us understand why the shoreline on the North Shore looks the way it does today. If these people (Elliottville residents) had been successful, it would be shoreline. It would be like a beach, like South Beach,“ Kaser said ”Previously there were ferry services around the Island. Not everyone had to come to St. George.”

Though the Elliottville residents were unsuccessful against Wiman, the families’ correspondence preserved over generations helped make Kaser’s work possible.

Personal correspondence of Elizabeth Gay and some members of the Shaw family were main sources the author used to paint his study of the Staten Island neighborhood.

“It‘s just such a series of accidents, because this Scottish eye doctor, initially, is thinking he’s going to create this therapeutic community on Staten Island. And, you know, he treats these New Englanders, and they’re attracted to his views because it’s medical reform,” Kaser said. “These were radical thinkers of the time who come together and live in this community and support each other at a time when their ideas were attacked with great hostility.”