For years, scholars have debated whether New York Bishop John Hughes did the right thing when he threatened the city’s mayor in 1844.

But no one doubts its effectiveness.

Just days before, anti-Catholic riots in Philadelphia had destroyed two Catholic churches and killed about seven people. The New York mayor, a Protestant, asked the New York bishop if he was afraid Protestants there would burn down Catholic churches if a planned gathering of anti-Catholic nativists took place near city hall.

“No, sir, but I’m afraid that some of yours will be burned,” replied Bishop Hughes, who had quietly organized armed Irish parishioners to guard Catholic churches in the city. “We can protect our own.”

The anti-Catholic rally in New York was canceled, and no churches burned.

It’s part of what makes Hughes the outstanding figure in a cast of mostly memorable characters — the 13 heads of what is now the Archdiocese of New York, one of whom St. John Paul II once reportedly called “archbishop of the capital of the world.”

This is the legacy the new archbishop-designate of New York, Ronald Hicks, takes on later this week. Currently the bishop of Joliet, Illinois, the 58-year-old prelate is set to become the Big Apple’s new archbishop on Feb. 6, succeeding Cardinal Timothy Dolan, 75.

Bishop Ronald Hicks celebrates a school graduation Mass for children in Miacatlán, Morelos state, during his visit to Mexico in 2025. (Photo: Nuestros Pequeños Hermanos Mexico)

Bishop Ronald Hicks celebrates a school graduation Mass for children in Miacatlán, Morelos state, during his visit to Mexico in 2025. (Photo: Nuestros Pequeños Hermanos Mexico)

While the new archbishop-to-be may chart his own course, if he’s looking for historical precedents, he has plenty of vivid options to choose from.

“When it comes to archbishops of New York, we were blessed with strong, powerful men. Each man fit the times,” said George Marlin, co-author (with Brad Miner) of Sons of Saint Patrick: A History of the Archbishops of New York, from Dagger John to Timmytown (2017) and chairman of Aid to the Church in Need USA, in an interview with the Register.

Why Does New York Matter?

In February 2000, when then-presidential-candidate George W. Bush wanted to make nice with Catholic voters after backlash from an appearance earlier that month on the campus of the anti-Catholic Bob Jones University in South Carolina, he sent a letter of apology to Cardinal John O’Connor, then-archbishop of New York, implicitly communicating through O’Connor to what Bush called “all Catholics.”

That’s because while the United States has no formal primate the way some countries do, the archbishop of New York is the closest thing.

“In terms of the American Catholic Church, the New York diocese is the most prominent globally,” said Karen Park, a historian of U.S. Catholicism. “I would say that the prelate who leads that diocese is really the leader of the American Catholic Church.”

That’s the case even during tough times for the archdiocese — including now.

As with other places in the Northeast, the Archdiocese of New York by the numbers is on the decline, as decreases in Catholic population and in priests and seminarians and closings of parishes and Catholic schools suggest. But numbers don’t capture the pizzazz of the international center of commerce, media and culture.

“Even if the Catholic world in New York isn’t what it was, it still echoes throughout the Church and the world,” said Father James Garneau, a Church historian and priest of the Diocese of Raleigh, North Carolina, who grew up on Long Island, in an interview with the Register. “It is New York, and the city itself screams out for attention.”

Archbishop ‘Dagger John’ Hughes

The notion of New York City’s status as leader of the U.S. Church would have surprised observers 200 years ago. When the Diocese of New York was created in 1808 and became one of five dioceses in the United States, New York was third most important, behind Baltimore and Philadelphia.

New York rapidly outgrew other cities. Even so, it wasn’t obvious in the early decades of the 19th century what the New York Diocese would one day become. In fact, when Bishop Hughes was appointed to New York in 1842, it wasn’t clear that the diocese or the poor and despised Catholic community in the city were viable.

“It’s John Hughes who changes everything, along with circumstances and the politics of the day,” John Loughery, author of Dagger John: Archbishop John Hughes and the Making of Irish America (2018), told the Register. (The “dagger” refers to the cross Hughes signed his name with, which not only looked like a dagger in print but to Protestants seemed to capture his personality.)

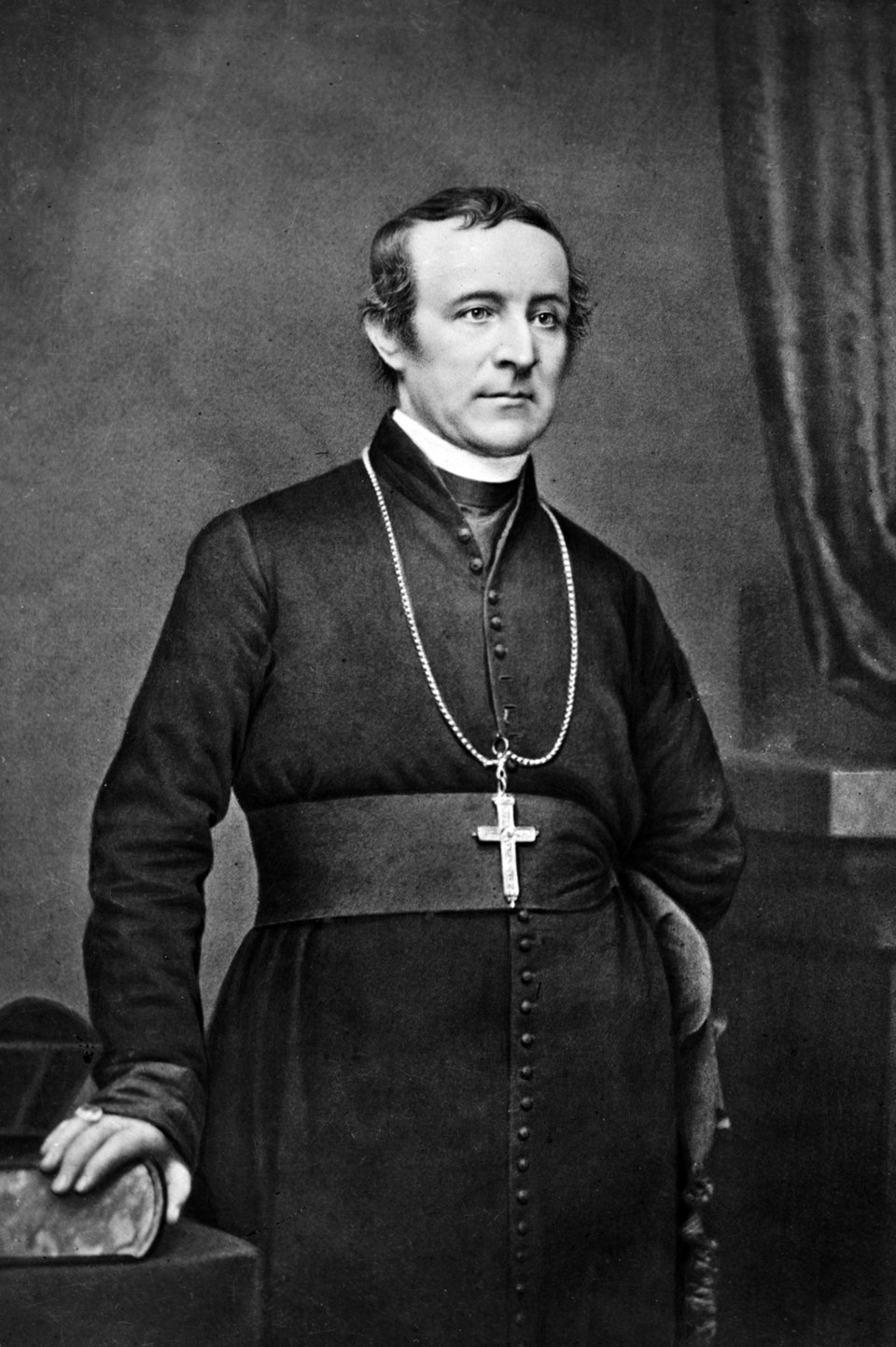

Bishop John Hughes.(Photo: Matthew Benjamin Brady )

Bishop John Hughes.(Photo: Matthew Benjamin Brady )

By the time Hughes died in 1864, the diocese had become well established and Hughes was a national figure.

Bishop (and as of 1850, Archbishop) Hughes debated Protestants over theology and history; fought against Protestant domination of public schools; built Catholic churches, schools and orphanages; defended Irish immigrants; represented the Lincoln administration in France during the Civil War; founded a college (now Fordham University); and envisioned and began building what is now the country’s most famous church, St. Patrick’s Cathedral on Fifth Avenue in Manhattan.

“He was a strong American, and he was not content with capitulating. He was trying to say, ‘No, of course we’re Americans. Of course we’re patriots. And of course we’re Catholic,’” Park told the Register.

His biographers describe a near-continuous state of crisis — not enough money, always under attack, struggling to provide for massive amounts of immigrants, and dealing with resistance from lay trustees who founded many Catholic churches and for decades ran them.

Critics then and now pan his dictatorial style and sarcasm, as well as his then-moderate views on slavery, which he didn’t think should end immediately.

No one ever denied his strength, though.

He became the face of American Catholicism, not only in its largest city but throughout the country, and remains today, according to Marlin and Miner’s book Sons of Saint Patrick, “arguably, America’s greatest Catholic leader.”

Cardinal Spellman: The Powerhouse

In 1939, 75 years after Archbishop Hughes died, his most powerful successor took over the archdiocese — Cardinal Francis Spellman, whom Marlin and Miner call “the most influential U.S. Catholic cleric on both the national and international stages in the history of the nation.”

Under Spellman, whose abilities in administration, fundraising and shaping events are unsurpassed among U.S. clerics, the residence of the archbishop at 452 Madison Avenue became known as “the Powerhouse.”

For an American, he had unparalleled access to the pope — Pope Pius XII was a friend and a former vacation companion from their days working in the Vatican’s diplomatic service.

He also had unusual access to presidents and other powerful politicians, who worried about what he thought about U.S. diplomacy with the Vatican, public funding for Catholic schools, and the moral content of movies, among other things.

Thomas Rzeznik, professor of history at Seton Hall University, noted that Spellman “expanded educational and social welfare institutions” in the Archdiocese of New York while also using his platform to help dictate social and political policies in the city, state and country.

“He commanded the loyalty of his Catholic flock, who supported his efforts to bring Catholic influence to bear on all aspects of American life,” Rzeznik told the Register by email.

As military vicar, Spellman traveled the world visiting American soldiers, sailors and chaplains, circumnavigating the globe three times. During a six-month trip during World War II, he visited national leaders in Europe and Africa to deliver secret diplomatic messages on behalf of President Franklin Roosevelt and Pope Pius XII.

Archbishop Spellman distributing holy communion at mass during a visit to the US Fifth Army in Italy 1944 during World War II.(Photo: Signal Corps Archive from Ireland)

Archbishop Spellman distributing holy communion at mass during a visit to the US Fifth Army in Italy 1944 during World War II.(Photo: Signal Corps Archive from Ireland)

Critics found Spellman petty and vindictive. Some criticized him for his unflinching support for U.S. military actions, including during the Vietnam War.

Among those who felt his sharp elbows was then-Bishop (and now Venerable) Fulton Sheen, who, according to John Cooney’s 1984 book The American Pope: The Life and Times of Francis Cardinal Spellman, refused in 1957 to fork over hundreds of thousands of dollars from the Society for the Propagation for the Faith (which Sheen ran) to Spellman’s archdiocese for powdered milk the federal government had donated. Spellman lost the milk battle but thwarted Sheen over the next decade, limiting his influence and stunting his prospects for advancement.

Notable Mentions

More recent New York archbishops have also grabbed national headlines, even if that wasn’t their goal.

Cardinal Terence Cooke

Leader of NYC’s archdiocese from 1968 to 1983, Cardinal Cooke presided over a rapid decline in numbers of priests, nuns and churchgoers amid widespread rejection of Church teachings and social disintegration in New York City post-Vatican II.

Yet this gentle, conflict-averse prelate emerged as a pro-life leader after the New York Legislature unexpectedly legalized abortion in 1970. He also envisioned and encouraged the founding in 1980 of what is now Courage International, which assists men and women attracted to members of the same sex to live chastely.

Cooke suffered physically as well as mentally — first from lymphoma and later from leukemia. Eleven days before he died, President Ronald Reagan and first lady Nancy Reagan visited Cooke at the archbishop’s residence.

A canonization cause for Cooke began in 1993. His current title in the Church is “Servant of God.”

Cardinal John O’Connor

Cooke’s immediate successor, Cardinal O’Connor, is even easier to remember because of his frequent brawls with New York politicians over abortion and homosexuality, among other things.

He clashed with longtime Gov. Mario Cuomo, a Catholic and supporter of legal abortion — and in 1984 he publicly and privately chastised U.S. Rep. Geraldine Ferraro of Queens, the Democratic Party’s vice-presidential nominee, for suggesting that that Catholic teachings on abortion are “not monolithic.”

Cardinal Timothy Dolan

Current administrator of the New York Archdiocese and archbishop from 2009 to December 2025, Cardinal Timothy Dolan has often served as the public face of Catholicism in the country, both as president of the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops (2010-2013) and in interviews and on talk shows.

How many times has Cardinal Dolan appeared on national television?

Hard to say, but one internet archive shows 123 transcripts mentioning his name on Fox & Friends, which doesn’t include other Fox News shows or NBC, ABC, CBS or CNN.

One reason is what Marlin and Miner describe as “Dolan’s jolly, outgoing personality.” Dolan put an emphasis on preaching, frequently saying Mass at St. Patrick’s Cathedral and releasing short talks online. He has also started a new series on faith-related “things worth recovering.”

“I view him as the evangelist,” Marlin told the Register. “He wasn’t a bomb-thrower like O’Connor, but he had a sense of humor and was able to work with all the conflicting forces in the Archdiocese of New York. He was a very talented orator and spokesman for the Church in the United States.”