The US Department of Health and Human Services is developing a generative artificial intelligence tool to find patterns across data reported to a national vaccine monitoring database and to generate hypotheses on the negative effects of vaccines, according to an inventory released last week of all use cases the agency had for AI in 2025.

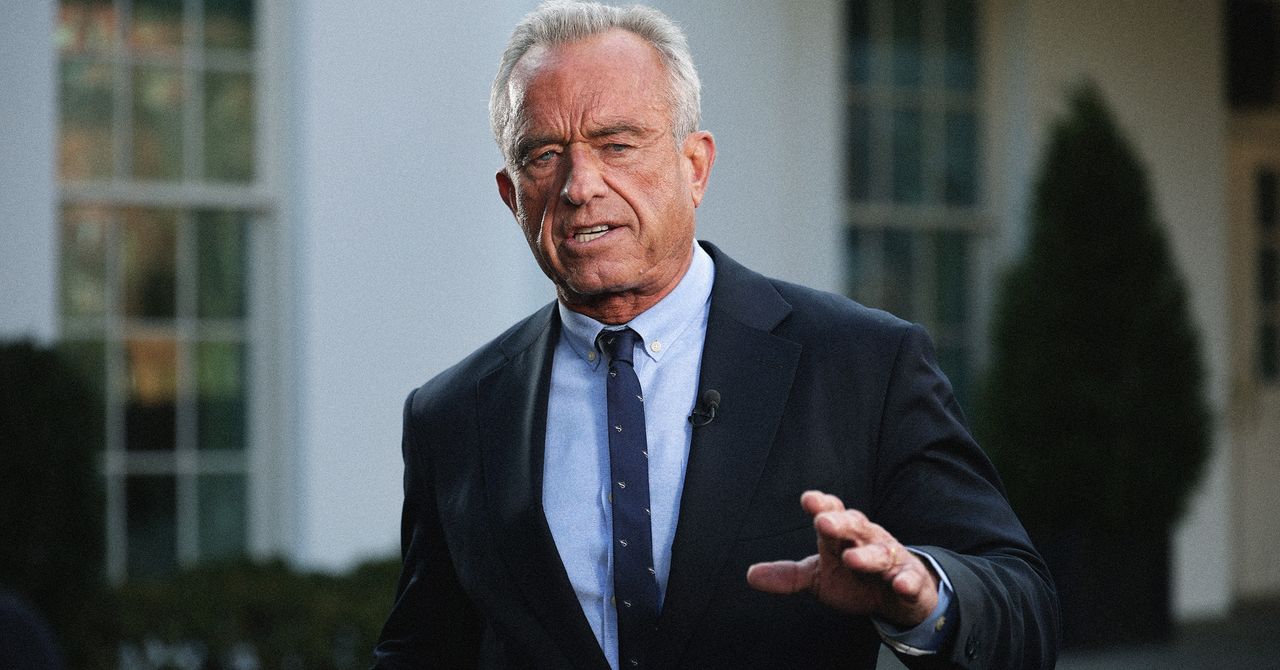

The tool has not yet been deployed, according to the HHS document, and an AI inventory report from the previous year shows that it has been in development since late 2023. But experts worry that the predictions it generates could be used by Health and Human Services secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr. to further his anti-vaccine agenda.

A long-standing vaccine critic, Kenedy has upended the childhood vaccination schedule in his year in office, removing several shots from a list of recommended immunizations for all children, including those for Covid-19, influenza, hepatitis A and B, meningococcal disease, rotavirus, and respiratory syncytial virus, or RSV.

Kennedy has also called for overhauling the current safety monitoring system for vaccine injury data collection, known as Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System, or VAERS, claiming that it suppresses information about the true rate of vaccine side effects. He has also proposed changes to the federal Vaccine Injury Compensation Program that could make it easier for people to sue for adverse events that haven’t been proven to be associated with vaccines.

Jointly managed by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the Food and Drug Administration, VAERS was established in 1990 as a way to detect potential safety issues with vaccines after their approval. Anyone, including health care providers and members of the public, can submit an adverse reaction report to the database. Because these claims are not verified, VAERS data alone can’t be used to determine if a vaccine caused an adverse event.

“VAERS, at best, was always a hypothesis-generating mechanism,” says Paul Offit, a pediatrician and director of the Vaccine Education Center at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia who was previously a member of the CDC’s Advisory Council on Immunization Practices. “It’s a noisy system. Anybody can report, and there’s no control group.”

Offit says the system only shows adverse events that happened at some point following immunization; it doesn’t prove that a vaccine caused those reactions. CDC’s own website says that a report to VAERS does not mean that a vaccine caused an adverse event. Despite this, anti-vaccine activists have misused VAERS data over the years to argue that vaccines are not safe.

Leslie Lenert, previously the founding director of the CDC’s National Center for Public Health Informatics, says government scientists have been using traditional natural language processing AI models to look for patterns in VAERS data for several years, so it’s not surprising that HHS would move toward the adoption of more advanced large language models.

One major limitation of VAERS is that it doesn’t include data on how many people received a vaccine, which can make events logged in the database seem more common than they actually are. For that reason, Lenert says it’s important to pair information from VAERS with other data sources to determine the true risk of an event.

LLMs are also famously good at producing convincing hallucinations, underscoring the need for humans to follow up on any hypotheses generated by an LLM.

“VAERS is supposed to be very exploratory. Some people in the FDA are now treating it as more than exploratory,” says Lenert, who is currently the director of the Center for Biomedical Informatics and Health Artificial Intelligence at Rutgers University.