The road for becoming a historian started with researching his family’s history, specifically his father’s side.

“I wanted to learn the Banegas family lineage, and I learned way more than I expected,” said Ethan Banegas, a descendant of the Kumeyaay, Luiseño/Payómkawichum, and Cupeño/ Kuupangaxwichem bands of Native Americans. “I know part of my father’s family history, way more than most people. I can literally trace my family history all the way back to the mission period and Father (Junipero) Serra. … For me, this is personal. One of the things I wanted to do is trace the historical trauma of my family from the mission period to the present, and it explained a lot of the reasons why the reservation was the way it was, why I struggled so much. It’s been therapeutic, it’s been a force of empowerment because that awareness and that truth being realized is like, ‘Oh, now it all makes sense.’ So, tracing my personal story was very therapeutic, and definitely kind of sad, too.”

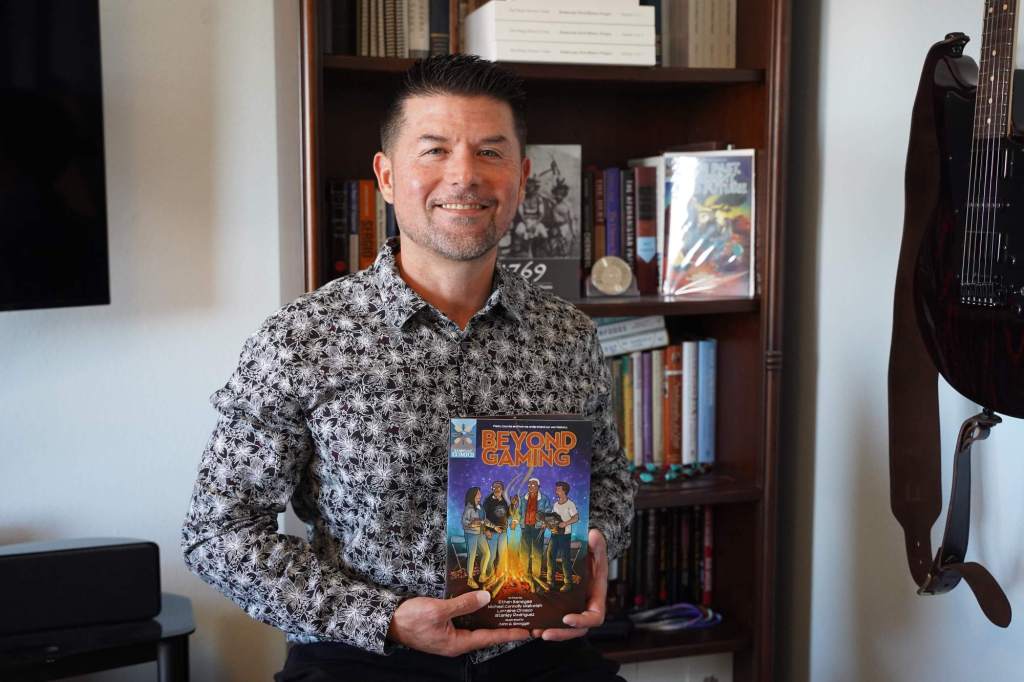

He grew up on the Barona reservation in San Diego County, spending about 40% of his time there with his dad after his parents separated when he was a kid. He describes his childhood as challenging, saying that he didn’t really like school and didn’t fit in. He tells people that education saved his life because it led him to his calling—history. He’s earned degrees in history from the University of San Diego, is co-owner of Kumeyaay.com, a historian for the San Diego History Center, conducted the Kumeyaay Oral History Project and the Kumeyaay Visual Storytelling Project community-based research projects, and recently published two comic books (“Beyond Gaming” and “Our Past, Present, and Future”) sharing the history of the Kumeyaay people from their perspective.

Banegas, 45, is also a professor at San Diego State University and lives in the La Mesa/El Cajon area with his wife, Celena, and their children Koa and Aakylee. He took some time to talk about how seeing the pain and suffering in his community compelled him to try and shift the imbalance of historical trauma to the truth, healing, and positivity that can come from telling their own stories and history.

Q: Looking back on your childhood, how did that time lead to your work on projects like Kumeyaay.com, working as a historian with the San Diego History Center, or teaching history at the college level?

A: Identity is a huge deal for me and for a lot of people. I didn’t look like everyone (on the reservation). When I went in the city, I looked more like people, but inside I was different. So, I was always somewhere in the middle. It’s funny because I say my curse became my blessing because it’s because I was in the middle that I was able to accomplish all these things and to make sense of all that pain and suffering, and make something beautiful out of it, which really reconciled that identity stuff.

Q: How did being in the middle in that way help facilitate that?

A: Being in the middle, I could really just be whatever I wanted. I didn’t fit in anywhere, so I didn’t care. If I were to pick, my heart and my soul are Native, but that’s just half of me. A lot of my destructive behavior was because of my identity crisis as a young person, I know that now. If I’d had someone older say, ‘Hey, this is who you are, Ethan. Who cares what anyone else says? This is what our ancestors defined us as, this is who you are. You’re this, only this.’ Those were the type of conversations I had with elders, and I really learned this during oral history projects, and it was the best therapy I could ever have, just talking to elders for hours.

What I love about La Mesa and El Cajon…

I love the diversity. I love that we have Chaldean communities, there’s Somalian communities, there’s all different races—Mexican, Asian, African American. El Cajon is the most diverse of all in San Diego County. I really believe that’s how I got some of, I call it power, in traveling because it felt like having that ability to adapt and just be cool with anybody. As far as the kind of people that come out of El Cajon because they have those experiences with different people? It’s priceless.

Q: Who were some of the Kumeyaay elders you spoke with during the information gathering portion of this community-based research, and how do we see their contributions show up in the comics?

A: I interviewed 33 elders from 13 different reservations. There were men, women, older, younger; I got a really good pool of data. There’s 56 hours of high-definition footage and 1,200 pages of transcripts, just to give you an idea of the project. I spent hours with all kinds of people. One thing I’ll suggest, and it’s the most important thing I got, is the diversity of opinion Native American people have. That is very hard to see when you’re reading a textbook or anything in media, so I always try to shine a light on the intense diversity of opinion and beliefs, religions, all that. We’re all so very, very different, so I think just having that really complex myriad of thought really helped me flesh out a lot of material on my end because I just wanted to make sure everyone was properly represented.

Q: Why is it important to you to develop projects that center the voices of Indigenous people? What kind of personal experiences have you had that have helped influence you toward more of this work, that documents and presents your community’s history from your point of view?

A: The reason why it’s so important is because no one in my generation was doing it, and if I didn’t do it, or someone like me, it would have died, you know? That’s just a simple fact. That’s what happens all across the world with language, history, with culture. That’s why that word “culture bearer” is funny to me because I’m a historian, but I teach culture more than I practice, ironically. I’m definitely trying to fix that. I think the main thing is I was always like, ‘Man, someone’s got to do that,’ and I would see the elders have this incredible wisdom. As an intern at San Diego History Center in 2017, I’d be like, ‘Man, this is an amazing story. When this elder passes away, this is gone forever and then the only people who will really know it is, maybe, their son or that daughter or cousin. Then, when they die, it’s gone.’ In a matter of time, all these stories are going to be gone because no one is recording them. The other thing was, if we do record these stories, how do we make them available to people? I was trying to solve all these issues and problems. I wanted to make a career out of it and get paid what I deserve, but it really was just thinking that someone’s got to do that.

Q: What is the best advice you’ve ever received?

A: I had a college professor whose advice was that the most important thing is to be working on your internal self. Not your material gain, your career, all that; that’s an empty road. Just the things that are fulfilling.

Q: What is one thing people would be surprised to find out about you?

A: How many places I’ve been because it’s a long list. I’ve traveled a lot and I’ve been to a lot of different places for a long time. I was in Haiti for six weeks after the earthquake, I’ve lived in England, Spain, Mexico; Korea for a month. I’ve kind of been all over the world, not just visiting, but living. I have a lot of experience as far as my awareness of the world and what’s in it. Because of my job, I continue to do that because I get to meet different kinds of people of different faiths, religions, belief systems. That’s something I thrive on.

Q: Please describe your ideal San Diego weekend.

A: We just had it. I went to the driving range and the batting cage with my son, my brother, my nephew, and my son’s friend. Then, we spent all day and had the best day in La Jolla. I went swimming and the lifeguard yelled at us because we went out too far, but it was cool. My daughter’s a little renegade like me, so she likes to push the limits. Just seeing my kids enjoy life, at the beach just swimming and being free. Just being with the people I love the most.