Why would an atheist suddenly leave her whole life– family, friends, home, career– for an indefinite stay with nuns in a cloistered religious community?

Perhaps “Stone Yard Devotional” written by Charlotte Wood epigraph, from songwriter Nick Cave, is a hint about our unnamed narrator’s motivations: “I felt chastened by the world.”

She is disillusioned with her long-term career in environmental conservation and justice work, overwhelmed by “all the world’s catastrophes, all the justice work undone, the poor unsupported, the natural creatures unprotected, rights unfought-for.” She is disappointed with her marriage and their life in Sydney. She is discouraged by perpetual grief over her parents’ death, even after 35 years.

“There may be a word in another language for what brought me to this place; to describe my particular kind of despair at that time,” she writes. “But I’ve never heard a word to express what I felt and what my body knew, which was that I had a need, an animal need, to find a place I had never been but which was still, in some undeniable way, my home.”

So she drives to her hometown in rural New South Wales and decides to stay with the nuns for a few nights– a chance to rest from the weight of everything and revel in silence and solitude. Upon her arrival she writes: “I find it hard to stop tears pricking my eyes, which alarms me. It is to do with being greeted warmly by a stranger, offered peace for no reason, without question. They have kind faces; warmth radiates from them.”

The narrator’s temporary retreat into monastic life becomes permanent. She keeps delaying her departure until it’s clear that she is just going to stay. But without any religious vows– she’s still an atheist, after all. But… maybe it’s not that simple? She is certainly wrestling with her own kind of faith journey throughout the novel.

She’s learning to live with the push and pull of hurting others and being hurt by them, asking for and extending forgiveness. “Sometimes I think this place is sending me insane,” she writes. “I fill with disgust at my own pettiness, punish myself by being extra nice to Dolores in small ways. Picking up her damn puffy vest from the floor for the millionth time.”

Perhaps the most difficult lesson for someone who was so devoted to changing the world, is accepting some things as they are– her past, her grief, her comrades– without trying to change them. Instead of reaching for change and control, she learns to bear witness and pay attention: “I shovelled the compost and spread it, shovelled and spread, preparing the soil and waiting for things to make sense. Tried to attend, very softly and quietly, which is the closest I can get to prayer.”

There are some external conflicts that move the plot along like a plague of mice that assails the property, chewing through walls and wires, garden and garbage. Also, the mother superior struggles to bring home the remains of a murdered sister, and the person escorting the body is someone from the narrator’s past who stirs up feelings of guilt and shame.

But rather than external conflicts, the narrator’s inner life is the most compelling part of the novel– a clear-eyed self-analysis that pulls no punches. The narrator’s reflections prompt big questions about leaving and staying and coming home, cruelty and kindness, guilt and forgiveness, life and death, past and present. Nothing much happens; we watch her life, and we contemplate alongside her.

“Stone Yard Devotional” is a quiet novel for chaotic times, full of the wisdom of a simple life.

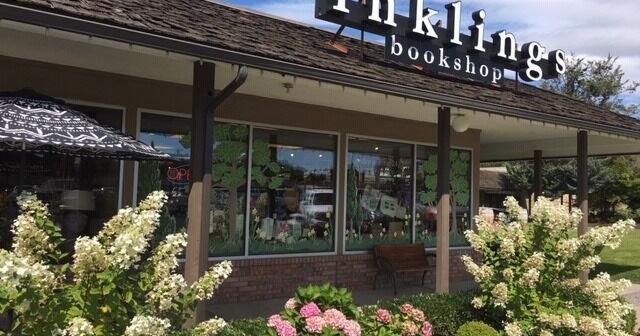

• Alicia McClintic is a book seller at Inklings Bookshop. She and other Inklings staffers review books in this space every week.