WIMBLEDON PARK, ENGLAND –It is a little before 9 p.m. and there is just one more night until the opening day of Wimbledon.

A short walk from the All England Club, or a long, orderly queue away, a Wales flag is draped on the side of a red tent in a nearby park. This is where “The Queue,” as the signs call it, starts.

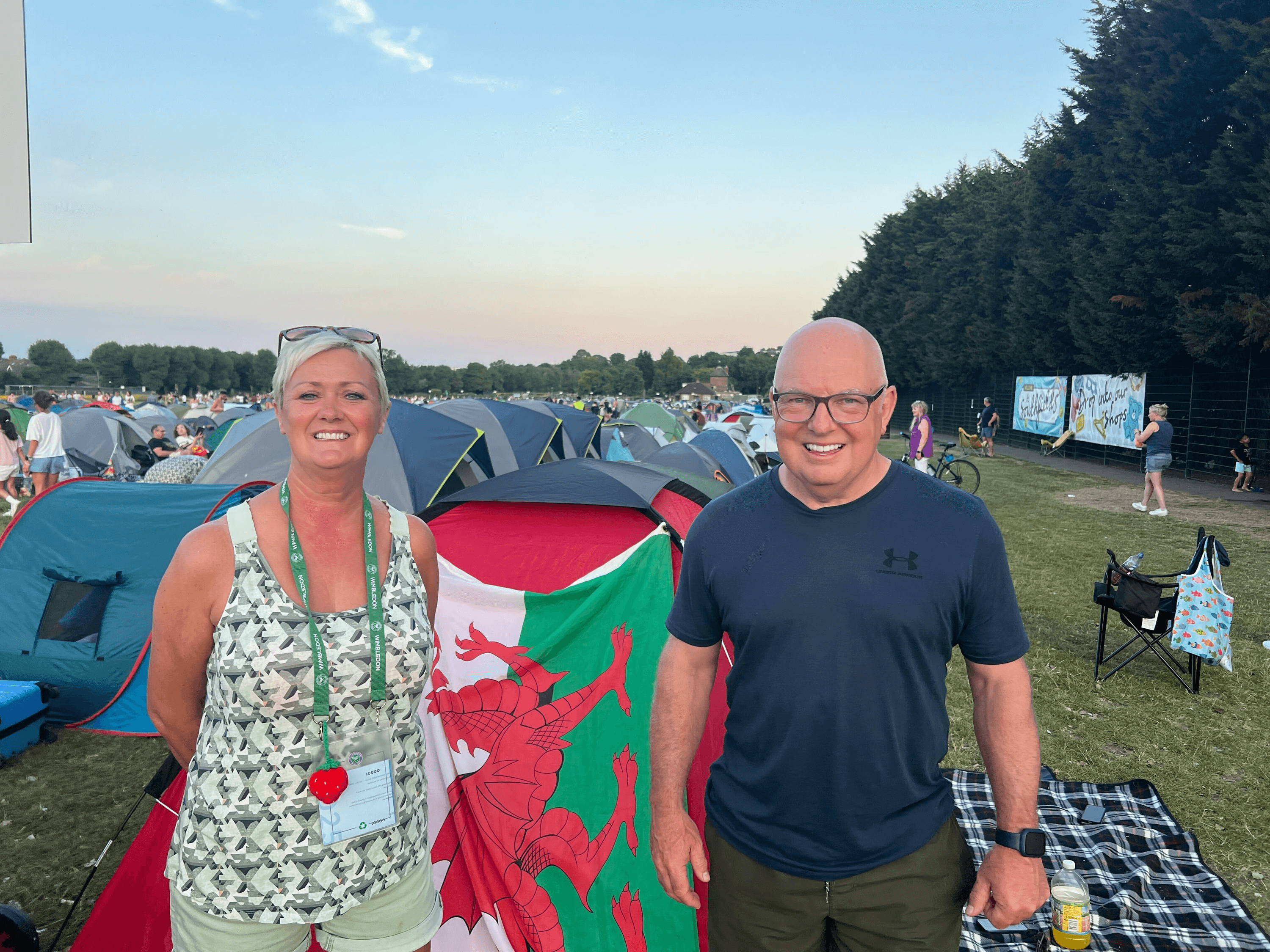

The flag belongs to grandparents Vicky and Nigel Broad, a couple of 41 years from Neath, a town about 10 miles from Swansea in south Wales — and nearly 200 miles from this corner of south-west London. They arrived at Wimbledon Park, a grassy parkland which for 50 weeks of the year is an ordinary suburban recreational ground, on Friday lunchtime and unofficially queued for two nights before they were given the No.1 queue card, putting them in prime position for Centre Court tickets on the opening day.

For the first 10 days of the Championships, the queue gives tennis fans an opportunity to secure tickets to the show grounds, Centre Court, No.1 Court and No.2 Court, as well as ground passes for all the other courts. It is a rare chance to purchase on-the-day tickets for one of the world’s biggest sporting events.

“There were three tents on Friday, 80 to 100 tents by Saturday and now there are hundreds,” Vicky tells The Athletic, as two people interrupt to congratulate her for being first in line. “We’ve had a lot of people stop and say ‘well done’ for being first.”

Nigel, an old hand at the etiquette of Wimbledon queues, recalls camping on the streets before getting in to see John McEnroe win his first men’s singles title in 1981, in the days when ‘The Queue’ wasn’t the organized snaking line of thousands it is today.

“For us, this is clearly the best sporting event,” Nigel says.

Vicky and Nigel Broad pictured at the front of the Wimbledon queue. (Caoimhe O’Neill/ The Athletic)

The couple are in a WhatsApp group with fellow campers who offer each other hints and tips, like where the nearest gym is to shower, given on site there are only toilets, a left luggage facility and food stalls, which will only open on Monday morning.

While the art of queuing dates back to the 19th century, this year’s Wimbledon queue, though a quintessential tradition, took a giant step into the 21st century by asking people to download an app on their phone so that they can be ‘checked in’ by a stewards via the Wimbledon App.

“We went to Roland Garros last year and it was lovely but it’s not Wimbledon,” Vicky says. “Every time you go in there, everything is as it should be. It’s beautiful, like you’re in a different universe.”

For many, the queue is also a place to switch off from the worries of the outside world. “For the time being, we don’t have to think about anything else,” Vicky adds.

It’s an escape for Linda Jacobs and Aleta Cole, too, friends who have flown in from Houston, Texas and are third and fourth in line having also arrived in the queue on Friday, 72 hours or so before the start of any actual tennis.

“I flew in Thursday overnight, got into London at 7.30 a.m. took the tube to my Airbnb, dropped off my luggage and came right over here,” says Jacobs, who was fifth in the queue last year.

“This is the safest camping you could ever do because everybody’s so nice and welcoming. There’s a guy who is in his 33rd year. You learn from all the veterans on what they do and how they do it. It has been really fun. There are people from all over the world. It is like a music festival without the drugs,” she laughs.

The rules for the queue are arguably a little more stringent than at festivals. For the uninitiated, there is a code of conduct: no music or ball games after 10 p.m.; no barbecues, camping stoves or fires — and takeaway deliveries must arrive before 10 p.m. If people need to leave the queue for ablutions or refreshments, they can take no longer than 30 minutes. Those queueing overnight are woken up by stewards in the early hours and told to pack up their tents to form a tighter formation for that day, but the edicts don’t dampen spirits.

One morning, The Athletic sees a big group doing yoga on the grass. No matter what day or time it is, there always seems to be people with rackets hitting a ball back and forth as though they themselves are on Centre Court.

“There’s no other Grand Slam that does this, it makes prices affordable for a lot of people. It’s unique and I’m not sure Americans would do the queue as well as the British,” Jacobs, who will return to the queue for the next three nights, says.

“We’re going to see three matches on Centre Court tomorrow for £105 ($140). The U.S. Open is more expensive than that,” Cole adds. “I’m not a camper, but I will camp for tennis.”

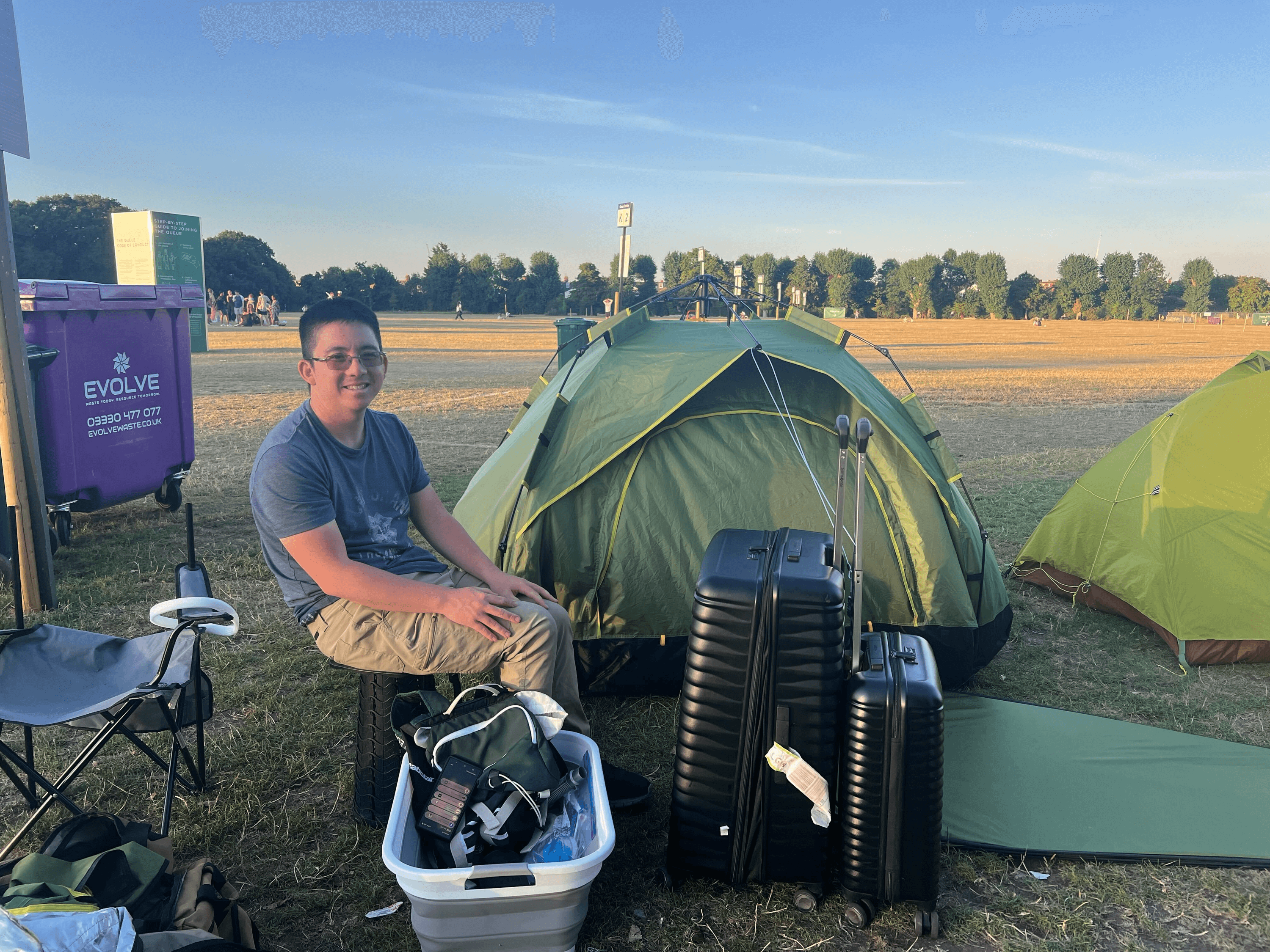

Brent Pham from California brought an outdoor shower with him to “The Queue.” (Caoimhe O’Neill/ The Athletic)

Though there has been rain and thunderstorms at times during the last fortnight, the main battle for queuers has been the humid temperatures. The green grass of the first night has given way to an arid, dusty version of itself.

Heading into the final Sunday, when Jannik Sinner will attempt to dethrone Carlos Alcaraz of the men’s title, there are still people camping. Fifty or so tents have been set up for the final night. If the mood in the queue on June 29 was togetherness, things have now taken a turn.

Fans are queuing up for ground passes in the hope of getting a good slot in the virtual resale queue, which will mean a race to the resale desk in the queuing village for 8.30 a.m on Sunday, an area where queuers can purchase refreshments and watch tennis on a big screen until the ground opens at 10 a.m. With not a lot of tennis on the outside courts, given there is only the men’s final and women’s doubles final on Centre Court on the last day, that is their only chance of seeing any live action.

“Everyone says it’s really stressful and not a nice experience,” says Neal Mehta, who is No 2 in the queue and has been camping for three nights.

“You make friends with people in the queue but everyone’s out for themselves, the 30-year-old from north London adds.

“Two nights ago, when it was the men’s semifinals, there were arguments and quite a bit of drama. Up until Wednesday (day nine), it’s a very organized system. They have a lot of staff and it’s very strict. For the last four days, it has basically been, not a free-for-all, but an informal queue.”

Many in this queue are feeling relieved Novak Djokovic did not make the final because his fans are, as Mehta puts it, “good at getting tickets.” Ahead of Mehta is Californian Brent Pham, who is the talk of the queue because he has brought his own outdoor shower. The 35-year-old has the No.1 queue card but is taking nothing for granted.

What the queue does best is bring tennis fans together. A lot of people return to camp again with the people they had previously met in the queue. Claire Johnson from Chicago is planning to meet Tim Chynoweth at next year’s Australian Open. Chynoweth, from Tasmania, is now an expert in queuing etiquette after spending 12 of the last 14 nights camping in the park.

Last year, the 31-year-old sports analyst paid £10,000 ($13,500) to be on Centre Court to watch Alcaraz beat Djokovic in straight sets. This year, he is hoping for a cheaper visit. With the No. 8 queue card in his pocket, he is optimistic but realizes the stakes are high.

“I’m not sure I would recommend it for the finals. It’s a real long shot,” says Johnson. “They didn’t call very many people from the queue for women’s final tickets.”

Johnson, who successfully queued for men’s semifinals tickets, sums up the community spirit that still remains even though competition for tickets has cranked up a notch.

“One of the reasons I wanted to join the queue was for the experience,” Johnson says. “It can be difficult as a solo female traveler to feel safe and that your stuff is safe. But the fun part about the queue is who else you meet.

“At the beginning, I was a little nervous but they have security here and I’ve started bonding with other queue members. We are all watching out for each other and it’s an incredible experience to meet people from all over the world who are also huge tennis fans.”

(Top photos: Mike Egerton, Ezra Shaw, Julian Finney / Getty Images; Illustration: Kelsea Petersen / The Athletic)