Special Olympics Wisconsin has joined an international effort aimed at improving health care quality and access for people with intellectual and developmental disabilities.

Special Olympics announced the initiative last year, called the Rosemary Collaboratory. It’s named after Rosemary Kennedy who helped inspire Special Olympics. On Tuesday, officials with the organization’s Wisconsin chapter held a call with policy makers, health care providers and advocates to explain the work happening in the Badger State.

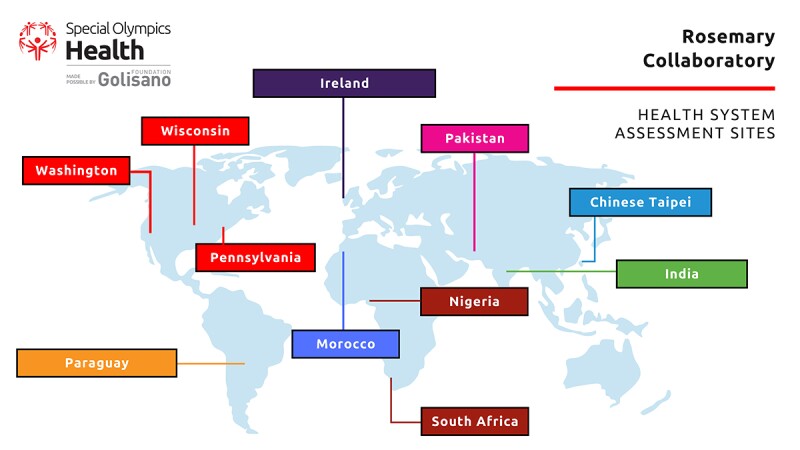

Wisconsin is one of 11 Special Olympics chapters worldwide — and one of just three in the United States — that are “health system assessment sites,” researching and leading efforts to improve health care for those with intellectual and developmental disabilities, or IDD.

Stay connected to Wisconsin news — your way

Get trustworthy reporting and unique local stories from WPR delivered directly to your inbox.

Wisconsin’s team will focus on three long-term objectives: strengthening medical education to ensure health professionals can effectively care for patients with disabilities, improving Medicaid reimbursement rates and partnering with the state and advocates to improve health care and social services.

“Special Olympics Wisconsin’s mission has traditionally led us to focus on the work of our athletes and programs that support them,” said Chad Hershner, president of Special Olympics Wisconsin. “By participating in the collaboratory, it enables us to expand our scope to all individuals with IDD in Wisconsin.”

In the Badger State, there are around 42,000 adults and children with intellectual and developmental disabilities who receive long-term services, according to Special Olympics Wisconsin.

Hershner said the organization been gathering information on the current state of care in the state using interviews and surveys of people with IDD and health care providers.

“In a 2024 survey of people with intellectual and developmental disabilities in Wisconsin, only 54 percent of those people with IDD reported that their health care providers gave them enough attention to meet their needs,” he said. “Clearly, there’s opportunity to move forward together.”

One of the people who struggled to feel they were really heard by their medical provider is Drew, a Special Olympics athlete who lives in De Pere. On Tuesday’s call, Drew said he was diagnosed with epilepsy in 2005. He said he works with a neurologist who “doesn’t believe” him when he tells him about his seizures.

“He wants to make sure that other people witness me having them, and I know my body,” he said. “I’m the best resource when it comes to my seizures. … I would never lie about my seizures because I’m aware when I’m having them.”

This graphic shows where the different Special Olympics chapters participating in the Rosemary Collaboratory are located. Wisconsin is one of just three chapters in the United States that serves as a “health system assessment site.” Graphic courtesy of Special Olympics Wisconsin

This graphic shows where the different Special Olympics chapters participating in the Rosemary Collaboratory are located. Wisconsin is one of just three chapters in the United States that serves as a “health system assessment site.” Graphic courtesy of Special Olympics Wisconsin

The organization identified Special Olympics athletes only by their first names in the call Tuesday.

Hershner said Special Olympics Wisconsin plans to start addressing the education piece of its goals through conversations with physicians, nurses and physical therapy professionals. He said a 2023 state grant already allowed Special Olympics Wisconsin athletes to train more than 1,300 medical students and providers on how to work with individuals with intellectual and developmental disabilities.

On the Medicaid side, Hershner said providers often face reimbursement rates that don’t keep up with the cost of care, while those with disabilities are more likely to struggle with accessing care.

“Persons with intellectual and developmental disabilities were 33 percent and 49 percent more likely to lack annual clinic evaluations and management visits for primary and specialty care, respectively, than those without disabilities,” he said. “We know there’s great work to be done here on both sides to improve access to quality care.”

Travis, a Special Olympics athlete from Manitowoc, said on Tuesday’s call that he was on Medicaid in the 1990s and early- to mid-2000s. During that time, he said the only dental care that was properly reimbursed was tooth extractions.

Now, he said he’s on his wife’s private insurance through her employer, but he’s hesitant to seek dental care.

“I’m still fearful of going to the dentist at this day because they don’t know how to deal with people with intellectual disabilities,” Travis said. “I think that cost is not affordable for private health care, and being on Medicaid did not help in the long run for me.”

In addition to facing challenges with Medicaid, Hershner said people with IDD often have to interact with “dozens of systems and programs throughout their lives” to receive necessary care, ranging from health care to social services.

He said navigating the full range of services needed to stay healthy and employed is often “painfully overwhelming” and “very confusing.”

“You have a great deal of experience trying to navigate systems to support you and your care, but these systems may not have been necessarily designed to work well for you,” Hershner said.

While Special Olympics Wisconsin’s work with the Rosemary Collaboratory is still in the early stages, Hershner added that addressing those issues will require a team effort between stakeholders, ranging from state policymakers to health care providers.

“Together, we can improve the lives of individuals with IDD here in our state and be leaders in this movement across the globe to make lasting and transformational change,” he said.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.