Libby Mitchell was in the mood to celebrate.

It was 1993 and she’d just sold her recycled textiles business to a colleague. The pair decided to toast the deal in the local pub.

Little did Libby know, this seemingly innocuous night would spark an addiction that would consume her for more than two decades.

At the time, gaming machine venues called ‘Tabaret’ were on the rise.

One of the games was simple – pick six numbers from one to 100 and if all your numbers were drawn, you’d win. It was a similar game to ‘Keno’ seen in pubs today.

‘I had no idea I was using a pokie machine – I thought it was a bingo machine,’ Libby tells Daily Mail Australia.

‘One dollar was the minimum spend and I was placing 10c bets. I’d lose money but, every now and again, I’d win some back.’

Libby, a single mother of two from Mount Eliza, Victoria, says she was ‘hypnotised’ by the machine and a few weeks later, went back to play again.

For 22 years Libby Mitchell, a single mother of two from Mount Eliza, Victoria, suffered from a gambling addiction so severe she lost homes and businesses

That night she won $200 and after that started going a couple of times a week with friends.

Soon she was going alone after work, sometimes playing until 2am.

Within a year, she’d lost $2,000, which she says was ‘massive’ at the time.

Libby kept her addiction secret from her friends and two teenage daughters but over the coming years it worsened.

After six years she needed to get away and hoped a move would break the addiction so she decided to sell her house and relocate to Melbourne.

She received $100,000 from the settlement, part of which she invested in starting another business.

The rest of the money she gambled away, sometimes losing up to $2,000 a night.

By now she was gambling in the 24-hour Crown Casino. On one occasion she stayed for 52 hours straight, sitting ‘mesmerised’ in front of the chiming machines and desperately feeding notes into the slot.

Libby, pictured in 1993 when her addiction began, says she was ‘hypnotised’ by the machines

She paused only for coffee, a ham and cheese sandwich and brief bathroom breaks.

‘I left the house on Tuesday morning and didn’t come back until Thursday afternoon. My 20-year-old daughter was living with me and had been trying to reach me but I didn’t answer. She had no idea where I was,’ Libby says.

By the time she arrived home, she’d lost her last $5,000 and her daughters were ‘hysterical’ with worry.

‘They knew something was going on but they didn’t know what,’ Libby recalls.

Without a cent to her name, she had no choice but to come clean to her children.

While they helped Libby to find a counsellor, it wasn’t enough for her to escape the hold gambling had on her.

In the year 2000, she sold another business because she was ‘desperate for a regular payslip, stability and normality’ and returned to teaching Year 12 students.

For a time having a nine-to-five job stifled Libby’s addiction because she couldn’t head to the pokies any time she liked.

But it wasn’t enough. Instead she started going as soon as she finished work.

‘I went straight to a pokies venue and stayed there all night, then went to work the next day. I just felt like a zombie,’ Libby admits.

‘I drove home thinking, “I can’t do this to these kids – they’re three weeks away from exams. What have I done to myself?”‘

Libby, pictured with her daughters in 2010, estimates she’s lost at least $500,000 on the pokies over the years but admits the real number is likely to be considerably more

By now Libby was suicidal and on the brink of homelessness.

‘In the middle of the night, I drove to West Gate Bridge, stopped my car and stood on the edge,’ Libby says.

‘I had one leg over and couldn’t see the bottom. But then, out of nowhere, a ship came from underneath the bridge and sounded this massive horn.

‘The noise shot right up at me and woke me up. I hated heights and realised just how high it was. I climbed back over, got into my car and straight to the Royal Melbourne Hospital. I was terrified to be alone.’

Once again unable to afford rent, Libby was forced to move in with her father.

‘I wouldn’t be here if it weren’t for my dad and my daughters,’ Libby says.

‘But my father was tough on me – it was like I was 12-years-old again. He said, “Here’s the rules, you’re not going out, you’re not driving, and the only place you’re going is to the doctor or a psychologist.”

‘The hardest thing to face was the fact that I was such a failure. I was well-educated but was falling apart.’

Over time she learned gambling was an addiction just like smoking or alcoholism and she started to avoid the pokies altogether.

She managed to avoid gambling for a couple of years but fell off the wagon in 2002.

‘One night I went with my daughter to the pokies and she left at 10pm but I stayed until 2am and lost $1,200,’ Libby says.

Eventually, Libby went to the extreme of moving to Western Australia in 2005 where pokie machines were restricted to one casino and banned in local neighbourhoods.

‘I thought it would fix me, and it did because it broke the physical addiction – I couldn’t gamble. Thank God there was no such thing as online gambling then,’ she says.

For two years, Libby managed to avoid the pokies, but still hadn’t faced the psychological urge underpinning her addiction.

But after moving to regional Victoria because housing was more affordable, she relapsed several times.

In the years that followed, Libby learned more about the machines and became involved in gambling reform.

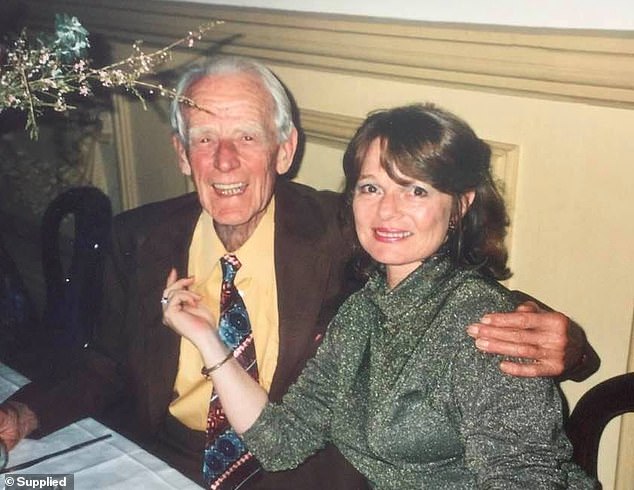

‘I wouldn’t be here if it weren’t for my dad and my daughters,’ says Libby, pictured with her father, left, and two daughters

By 2014, after losing her father, she had re-established herself financially.

‘I hadn’t gone in years, then over three weeks in 2015 I lost $30,000 – it was the biggest shock of my life,’ she says.

‘I managed to win $15,000 back, but for the first time in my life, instead of putting it straight back in the pokies, I took it to the bank.’

She vowed to never gamble again.

Libby estimates she has lost at least $500,000 on the pokies over the years, but admits it could be even more.

Libby, now 76, wants more action to be taken and strongly believes every Australian gambler must be registered. She says getting help once the addiction has started is often too late.

‘I believe that gambler licensing is the only sensible way to go forward where every gambler must register for a year and pay a licence fee like our drivers must pay. Something like $600 a year or $20 for 24-hour access should be doable,’ she says.

‘Some gamblers would be properly warned and deterred before they ever get addicted and the government would make the money required to fund some social costs of gambling.

‘Our employment levels would rise as traders would have more money going through their shop doors. Gamblers can easily lose $600 in one session, but the government does not profit from that loss. The gambling industry does.

‘If a person cannot afford the licence fee – then they should not be gambling at all. There are people regularly losing $14,000 in a weekend right now in Australia. Gambling is a scourge on our economy that must be better controlled.’

‘It’s the biggest all-cash, no-receipt industry in the world, yet it goes by unnoticed. Many blind eyes are turned – and we are too trustful.

‘Poker machines cause addiction to people who are not given proper product warnings. A toaster has more consumer warnings than pokies do. Recreational fishermen must buy a licence – it is absurd that we protect our fish more than our people.

‘Consumers should be registered to gamble – to force them to get a spending record. The government needs to know exactly how much money is lost from our communities, from gambling. A licence keeps everyone safer, including traders and taxpayers, who are the biggest losers from gambling, beyond the gambler and his family.’

If you need support, call the Gamblers Helpline on 1800 858 858 or Lifeline Australia on 13 11 14