Denis Staunton in Beijing

The rather forbidding food editor was icy in the clarity of her instruction: I was to find the best meal I could get nearby for two people with wine for €120. The problem was that at the nicest restaurant close to where I live in Beijing, it would be a struggle to spend a fraction of that on dinner for two.

So, she agreed to relax the rule to allow me to spend my allotted €120 on a dinner for eight at Shijin Garden, a Beijing homestyle restaurant tucked away on a quiet street behind a military hospital. You push through a heavy plastic curtain to enter a large, wood-panelled room with large tables, each covered with a check tablecloth beneath a glass top.

This is one of the most low-tech restaurants in Beijing, where you order from a printed menu and the server writes down your order with a pen on a paper pad. People of all ages dine here, but many come to taste simple, old-fashioned dishes as they remember them from decades ago.

Most dishes in Chinese restaurants are shared but we ordered rice for everyone at RMB2 (€0.24) per bowl, and we all had soup at a little less than €3 each. Four had hot and sour soup and the others had vegetable, beef, tomato and egg, or shrimp skin, cabbage and bean curd.

Most main courses are between about €5 and €9, but we splashed out on a whole sea bass with fresh chilli and a whole perch baked in tinfoil for €11 each. Portions are generous, but we ordered two Kung Pao chicken, a house speciality with the most tender and succulent chicken, a sweet-and-sour sauce less spicy than in the original Sichuan style, and crispy peanuts.

Beef tenderloin with a black pepper sauce arrived sizzling on an iron plate at the same time as a large plate of stir-fried streaky pork and some stir-fried mushrooms.

I insisted on ordering two portions of green beans with minced pork, which are a revelation. The greens are stir-fried until slightly wrinkled on the surface, with garlic, Sichuan peppercorns and fermented black beans and tiny pieces of minced pork.

Braised aubergine with chilli and vinegar came steaming in a white bowl alongside two large clay pots, one with thinly sliced braised potatoes and the other with thicker slices of braised lotus root. By now we had spent €96 on food but the meal was supposed to include wine – and that was a problem.

Like many similar places, this restaurant doesn’t really stock wine, but they allow you to bring your own and there is no corkage fee. Some of my friends wanted beer, which costs €0.70 for a half-litre bottle, and we ended up ordering 10 of them.

This brought the bill to just €103 so we ordered the biggest, most expensive bottle of baiju, a white spirit made from sorghum with a terrifyingly high alcohol volume – but it cost only €5. We could take no more, so although there is no tipping culture in China, we left the remaining €12 to the staff.

Sally Hayden in Damascus, Syria

You would struggle to spend €120 on a meal in Damascus. While I went out to eat with four others and ordered enthusiastically in order to research this article, our bill did not even come to half of that. Its total was just 525,000 Syrian pounds (about €39.18).

We went to Beit Jabri, a restaurant in the courtyard of an old Damascene house. It is reached by ducking through an unassuming low wooden door in one of narrow streets of the old city. The restaurant opened in the 1990s, though the house is almost 300 years old. It is owned by the Jabri family – “The owner sits here all day,” an employee said, gesturing towards one corner. In the centre of the courtyard is a large water fountain, and several orange trees grow among the tables. Staff are happy for customers to look around other rooms in the building too.

I first came to this restaurant in the heady days after Bashar al-Assad’s regime fell last December, so it was lovely to return.

Most Syrian meals are meant for sharing, with one brave person usually stepping up to order for the table, and others contributing suggestions.

Usually, you include some salads (we went for both rocca salad and fattoush, a staple which includes crispy pieces of bread), and dips (we got Beiruti hummus, which comes with parsley, and Moutabal, made with aubergine). Meat-wise, we had chicken in a white sauce, which was served in a pot; helabi kebab – a ground beef kebab baked with onions and tomatoes, which was accompanied by cooked tomatoes and bread; and chicken livers (these are not to my personal taste, though my friends love them). We also ordered plates of rice and spicy batata harra, or crispy fried potatoes.

The entrance to Beit Jabri, a restaurant in the old city in Damascus.

The entrance to Beit Jabri, a restaurant in the old city in Damascus.  A shared meal between five people in Beit Jabri restaurant, in Damascus, came to less than €40.

A shared meal between five people in Beit Jabri restaurant, in Damascus, came to less than €40.

Of course the bill would have been more expensive if alcohol had been included: while it is possible to get alcohol in some restaurants, Beit Jabri, like many others in Syria, does not serve it. We instead ordered water for the table and finished off our meal with a cup of tea each. Other non-alcoholic drinks are available, including a peach slushie (34,000, or €2.53), a caramel frappé (45,000, or €3.36) and a “Blue Hawaii” (30,000, or €2.23).

Some diners were smoking argileh, or shisha, at their tables; it was available for 30,000 Syrian pounds (or €2.23) in flavours including apple, grape, bubblegum and blueberry. Desserts on the menu included a chocolate pancake (45,000 pounds, or €3.36) and a fettuccine crepe (65,000 pounds, or €4.85).

Another restaurant nearby had an oud player who performs as you eat, but Beit Jabri reserves musical performances for Monday nights, when it staff remove the tables and different singers and musicians are invited. Tickets can sell out a week in advance, according to a staff member.

If you want a starter or something sweet on the way to or from a meal in Damascus (or as a separate meal altogether), I recommend getting a “cocktail” – juice, which can include liquidised avocado, served with ashta (a type of cream), nuts and some chopped up fruit. It’s usually eaten with a spoon. Or you could get a serving of baklava, knafeh or another of the many desserts from one of shops and stands around the old city, which will set you back a few euro or less. instagram.com/beit.jabri.restaurant

Mark Paul in London

The concept of “the best meal available” is flexible and adaptable. What is “best” depends on what you fancy at a given moment, where you are, and who you’re with. Thankfully, London is a kaleidoscope of global cuisine – whatever your stomach’s desire, it is always available somewhere.

For example, there is a woman, Maureen Tyne, who serves world-class Caribbean jerk chicken in her back yard in Brixton. If I was on Electric Avenue some sunny day and the hunger pangs struck, the best – by far – meal available would be down at Maureen’s Kitchen: a hearty feed for about £15 (€17). In that moment, nothing else would beat it.

If it’s a Sunday afternoon during the football season and you’ve managed to get rid of the kids for a few hours, the best meal available is a British roast in a pub with a television and – this is crucial – dire mobile coverage (common in London). I never cared much for Yorkshire puddings until I moved here. I’ve since learned they make handy receptacles for gravy. Pour it in, dip your carrots, then wait for the pudding to burst.

For a reporter who spends more time in Westminster than any sane Irishman should, the “best meal available for €120 (£105)” usually means the best and most convenient political power lunch. For me, that is often to be found in Osteria dell’Angolo on Marsham Street, five minutes around the corner from Westminster Abbey.

Osteria dell’Angolo is a modern, fairly posh Italian restaurant across the street from the Home Office. It has white tablecloths and discreet staff. It is also packed full of politicos all week. It isn’t the best Italian restaurant in London, nor is it the poshest. But if you want to get an MP or political adviser talking in the middle of a work day (when you can’t get them too drunk), Osteria dell’Angolo’s all-round offering often does the trick.

The first thing you learn when meeting Westminster MPs for lunch is that most of them will never, ever pay for anything. MPs as a species are still collectively scarred from the Daily Telegraph expenses scandal of more than 15 years ago. The thought of someone discovering they claimed from taxpayers for a posh meal with Prosecco on a work day is enough to put the fear of God in them. I pay just to stop them from falling into panic before my eyes.

That means I always have to be mindful of the cost. In an ideal world, we both order from Osteria dell’Angolo’s three-course set lunch (£31.50 each) and the cheapest bottle of wine (about £30). Factor in the 12.5 per cent discretionary service charge automatically lobbed on to every bill, and it comes to exactly £105. Perfect.

The set lunch menu might include classic Italian dishes such as zuppa di piselli (pea soup), polipetti (stewed baby octopus) and fegato alla piastre (fried calf’s liver).

Osteria dell’Angolo restaurant in London

Osteria dell’Angolo restaurant in London  A dish from Osteria dell’Angolo

A dish from Osteria dell’Angolo

One of the first politicians I took to Osteria dell’Angolo was Alex Salmond, Scotland’s former first minister who was once an MP. It was soon after Nicola Sturgeon, his one-time protege and later enemy, quit. I wanted someone who really knew Edinburgh politics to give me a view on what this all meant for the push for Scottish independence.

Salmond was generous with his knowledge and wit, a charming companion. But whatever else he was, he wasn’t really a man for a fixed-price set lunch. Salmond joyfully waltzed his way through the dearer a-la-carte menu. He also liked good wine. The rogue blew my budget, but I didn’t care. He was worth it. While I spoke to him many times afterwards, I never ate lunch with Salmond again – he died the following year.

Since then I have eaten at Osteria dell’Angolo with people from parties including Reform UK, Labour, the Tories and more. I have dined there with diplomats, lords, MPs and their advisers. There is cross-party consensus that Osteria dell’Angolo does a fine lunch. osteriadellangolo.co.uk

Derek Scally in Berlin

October – Oktober, even – is when German food has its chance to shine. Oktoberfest beer tents in Bavaria – and, increasingly, around the world –showcase popular pub grub fare like Bratwurst, Schnitzel, and roast pork knuckle. But there is a lot more to German food if you know where to look. Ask me about my best meal here in Germany and I would point to an unassuming restaurant in western Berlin called Weiss – White – named after the its owner-operator couple, Ewald and Ilona Weiss.

For 15 years, the couple from Swabia in southwestern Germany have served up food that, like their restaurant, is spectacularly unspectacular. Restaurant Weiss operates to an old-school principle that quality – in ingredients, preparation and presentation – speaks for itself.

It’s hard to pick just one good meal, but here is my most recent. To start, I had a house speciality: veal sausage, or Weisswurst, in breadcrumbs and baked in the oven, served with fresh sauerkraut with tangy vinegar and caraway seeds. It’s a deceptively simple dish, combining two kinds of crunch and a creamy meat consistency.

My partner went full Swabian with veal tongue, a cloud-like soft meat, on a bed of lentils in a juicy Madeira-based sauce. For the main course, we shared two dishes. One was the Weiss customer favourite: the juiciest, most tender breaded fried chicken you will ever taste (I could tell you the secret but Ewald would be mad), combined with the house potato salad, creamy yet light. The Weiss Backhendl is my definition of happiness on a plate, something that never disappoints.

Ilona and Ewald Weiss in their eponymous restaurant. Photograph: Derek Scally

Ilona and Ewald Weiss in their eponymous restaurant. Photograph: Derek Scally

The other dish was new to us: roast deboned quail with poultry stuffing, morel mushrooms, creamy mash and crunchy carrots. The stuffing is key here, as it enriches the quail with herby flavour while ensuring the bird stays moist and keeps its volume. The vegetable sides are mouth-poppingly flavourful; my partner is delighted at “how the carrots taste so carroty”. Both mains showcase the modest Weiss superpower: high-end Swabian country house cooking with the occasional detour to neighbouring France.

With that in mind, for dessert, we shared a light Crêpes Suzette with vanilla ice cream on a bed of triple sec sauce. To complete things, we each had a glass of home-made cherry schnapps. Accompanying us through our meal was a spectacular Chardonnay from Germany’s Pfalzregion, rich and elegant from oak barrique barrels. If you think German whites are all zingy Rieslings, this Petri vineyard wine will force you to think again.

The Weisses run the entire restaurant themselves, with Ewald in the kitchen and Ilona front-of-house. No corners are cut here: crisp tablecloths, fresh flowers and, on the walls, new art from local artist-customers. It’s a little off the tourist track, on a busy street in Berlin’s western Charlottenburg neighbourhood. But Weiss is well worth the visit. The three-course dinner for two menu – €44.50 each – with a bottle of white wine at €35, came to €124. You could add €15 to the menu price for accompanying wine with each course. restaurantweiss.de

Jack Power in Brussels

I had liked the look of a local vegan restaurant in Brussels so much that I’d taken to recommending it to people before I’d even eaten there myself.

After a while I thought that I better try the place, in case the food tasted like dried leaves and I picked up a reputation for giving out dodgy recommendations.

Verdō, in the suburb of Flagey, describes itself as the first “entirely plant-based brasserie in Brussels”.

On the evenings where I opt for the 40-or-so minute stroll home from work in the EU institutions, my walk usually takes me past the restaurant. It was on one of these walks back to my apartment in the neighbouring suburb of Ixelles that my partner and I stopped for dinner.

Verdō restaurant, in the suburb of Flagey, Brussels. Photograph: Jack Power

Verdō restaurant, in the suburb of Flagey, Brussels. Photograph: Jack Power

I’m not a vegan or vegetarian, bar a six-month period when I was 13 and listening to too much of The Smiths, but I have been happily surprised by plant-based restaurants in the past. Verdō is the best I have yet tried.

Traditional belge dishes tend to be centred around meat and carbs, which would be up my typical culinary street. The Belgians have got better at offering veggie and vegan options on menus in recent years, and you will get a choice in pretty much any restaurant now.

In Verdō I went for a zucchini risotto with vegetable parmesan and basil cream. On at least two occasions during the meal I remarked that it tasted so good I couldn’t believe it was vegan (sorry, vegans).

My partner went for a pressed aubergine steak glazed in a teriyaki sauce, with a potato and courgette mille-feuille, which was also delicious.

Verdō changes its menu every month or two and most of the wines are in the mid-€30s range for a bottle. The menu offers a two-course meal with organic or natural wine pairing for €55 per person, or a similar three-course option for €66.

Verdō advertises itself as more than just dog-friendly; its menu offers a dish “for our four-legged friends”.

Verdō Brussels: Salade d’Asperges. Photograph: Michael Binkin/YourStory Agency

Verdō Brussels: Salade d’Asperges. Photograph: Michael Binkin/YourStory Agency

I spotted at least two dogs accompanying owners during our visit. One was calmly lying under a table of four friends outside, across from us; another was sitting by a table inside.

This is the kind of restaurant that has a section on its website explaining the “concept”, beside tabs to have a look at the menu or book a table.

“We offer you gourmand dishes, inspired by Belgian gastronomy and concocted without any animal products,” it says. “From Wednesday to Friday evening, we bring together vegans and omnivores,” it goes on.

The vibe doesn’t feel holier-than-thou at all, although the lovely woman serving us was wearing those shoes that are actually more like socks. We had a table out on the street – this was still during the warmer evenings – so I’d say the shoes needed a decent wash at the end of a shift. Staff footwear aside, I’d very much recommend. verdo.brussels

Daniel McLaughlin, Ukraine

Odesa’s hospitality has long been celebrated in Ukrainian films and songs, and is reflected in the nickname given to this port city by the Black Sea: Odesa Mama.

It conjures up the image of a kindly but formidable matriarch, always fussing over loved ones, feeding them fantastic food and ignoring their indiscretions – and Odesa has always valued pleasure over propriety – before sending them on their way with a fierce bearhug that makes them, albeit briefly, consider the error of their ways and regret eating quite so lavishly.

Now let’s imagine that this Odesa Mama, some time in the late 19th century, was befriended by artistic and slightly eccentric aristocrats and asked to cook for them at their beautiful country home. The result would have been something like Dacha.

For two decades, this restaurant on Frantsuzky Bulvar (French Boulevard) has offered an escape from the quotidian and the clamour of modern life. It is more precious than ever now, after nearly four years of all-out war and frequent Russian missile and drone strikes on the city.

Dacha sits in a large garden that is allowed to run a little wild. In the warmer months, flowers grow where they will and cats snooze under hammocks strung up between the tall trees that provide shade for the tables dotted around the grounds.

Dacha restaurant in Odesa, Ukraine.

Dacha restaurant in Odesa, Ukraine.

A pale stone path meanders through the bushes and past a tinkling fountain to the main building, a small manor house whose dining rooms manage to be both elegant and homely, airy in summer and cosy in winter, when snow sometimes fills the garden.

The menu is as welcoming as the setting, combining fine renditions of Ukrainian classics with dishes that reflect the strong influence of the Jewish community on Odesa and its cuisine. It is satisfying food to be enjoyed at leisure, in any season.

The plate of Odesa appetisers includes bowls of forshmak, a traditional herring pate; a rich aubergine and red pepper spread that Ukrainians call “eggplant caviar”; an exquisitely light and melting gefilte fish; a fan of tiny silver sprats, and challah bread. It is a perfect introduction to the city’s food, for less than €25.

A selection of dishes at Dacha restaurant in Odesa, Ukraine.

A selection of dishes at Dacha restaurant in Odesa, Ukraine.

The aroma of wood smoke can be hard to resist, especially on a warm day in the garden, so how about something from the barbecue to follow, perhaps grilled trout, tender veal chops or juicy pieces of pork or chicken roasted on the skewer, shashlik style. They all go well with a bowl of tiny buttered new potatoes in summer or, in the chillier months, creamy porcini mushrooms on a bed of mashed potato.

Favourite Ukrainian desserts on the menu include nalysnyky – sweet pancake rolls stuffed with curd cheese and baked in a pot – and plump varenyky dumplings with cherries.

Dacha is a celebration of this city and of Ukraine, of their food and hospitality and resilience during wartime. So why not toast them with a bottle of sparkling Kolonist Bisser Brut (€45), made from chardonnay grapes grown near the coast in Odesa region. Savva-libkin.com/en/restaurant/odessa/dacha

Keith Duggan in Washington DC

You won’t live the high life in Washington DC on a dining budget of €120, but nor will you starve. The return of Donald Trump in January this year coincided with a prolonged winter blast of snow and the sense of an entirely new era in the city. Within weeks, Butterworth’s, on Capitol Hill, began appearing in news and magazine articles as a popular meeting spot among the ascendant Maga set – it was the restaurant of choice for Steve Bannon when he participated in the “Lunch with the FT” feature, cheerfully assuring readers that Trump would run for a third term.

Aside from attracting Maga-ites it has drawn rave reviews for an unfussy reimagining of standard bistro favourites and terrific staff. They’ll happily let you in the door in Butterworth’s with your modest budget. But it won’t take them long to serve you. You could book an evening dinner table, split the crispy cauliflower with miso caramel ($18), have mains of dry-aged duck breast with kale and sauce verjus ($37) or lamb heart Bolognese ($29, and a Maga fave, one imagines), definitely forsake the cocktail menu and have a couple of glasses of Sancerre – and still leave a standard tip of at least 20 per cent.

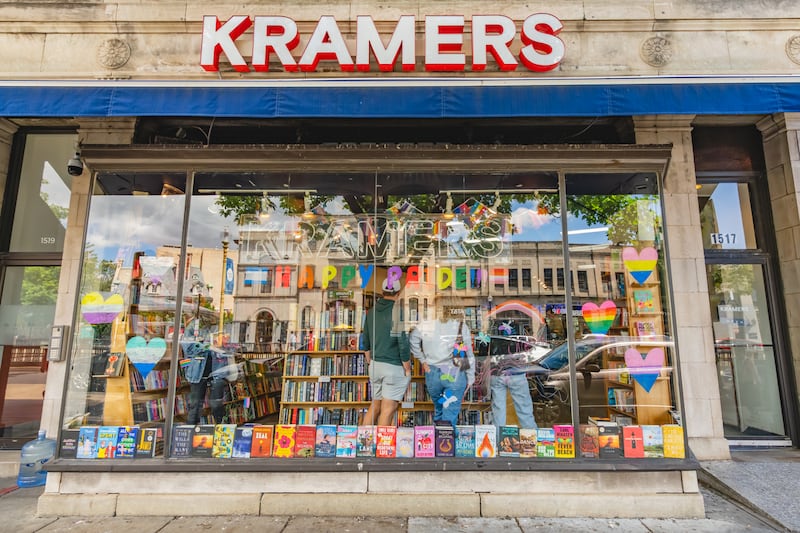

But a better option, on this budget, would be to take yourself off to one of Washington’s venerable old haunts, Kramers. It’s essentially a wonderful independent bookshop masquerading as both a bar and cafe/restaurant that has been a fixture on Connecticut avenue, just above the famous green and water fountain on Dupont Circle, since the 1940s. It was where the concept of the bookshop cafe originated in the United States and for a time, in the boozier decades, it remained open all night.

Now, like much of Washington, the shutters come down early. Celebrated past visitors include Maya Angelou and Barack Obama, but the place hit national headlines in 1998 when the owner, Bill Kramer, fought a court petition from independent counsel Kenneth Starr to have the bookshop reveal the titles of the books bought by one of its customers, Monica Lewinsky.

Kramers bookshop cafe in Washington, DC. Photograph: Getty

Kramers bookshop cafe in Washington, DC. Photograph: Getty

It’s a hugely popular weekend brunch location, particularly when it’s still warm enough to sit outside. Unsuspecting first-time visitors often move from the poetry section through a narrow doorway and in to the darkened bar, mirroring the pathway of many an actual poet. The bar is low-lit, even during the day, The restaurant is at the rear.

Decor is minimalist, to put it politely, but the menu is eclectic and everything is good. Steak and eggs ($29) and Kramers Benedict ($22) are brunch staples. For dinner, the cream of crab soup ($14) is served with grilled ciabatta and the crispy Brussels sprouts ($12), with lemon, parmesan and a side of ranch dressing, do much to rehab the reputation of that maligned veg.

Pizzas and those ginormous American sandwiches also feature, but highlights on the mains are blackened salmon ($25) and the shrimp and grits with andouille sausage in a spicy tomato sauce ($22). It’s the sort of place that invites parking of calorific anxieties at the door.

The Triple Chocolate Devil’s Food Cake ($12) is the best reason to visit Kramers, and possibly Washington itself. It’s an obscenity, in the best sense. The wine list is short and modestly priced: a bottle of the (only) Sauvignon Blanc is $35. So that’s a three-course meal for two for $120 (if you skip the caffeine) – a bill which would suggest a tip of around $30. And you might even pick up a book. kramers.com