This desire for unity between farmer, hunter, maker, forager, cook, and diner has inspired countless chefs in the decades since “Auberge” was published, including Alice Waters, Dan Barber, René Redzepi, Enrique Olvera, and Samin Nosrat. It hardly matters that the book is, essentially, a work of fiction. The text, which never acknowledges de Groot’s blindness, is full of descriptions of the auberge’s beauty that were likely flights of his imagination, such as the building’s gray stone walls, which are partly covered in roses and which de Groot first encounters washed in the pale light of a late-autumn morning.

In the years since the book was published, many “Auberge” devotees, including Waters, have made pilgrimages to the Alps in search of the mythic inn, and found something far less enchanting. “Of course, it existed for him,” Waters said tactfully, in a New Yorker Profile from 2014, when asked if the place was real. “It still exists for us, in the minds of the people around this table. Maybe that’s where the ideal restaurant always will be.” The cookbook author David Lebovitz told me that he didn’t even bother trying to find the auberge back when he was travelling in the region, even though the book had meant so much to him. He thought it’d be sad to go after so many years had passed.

In a 1966 Times profile by Craig Claiborne, published after de Groot’s first cookbook, “Feasts for All Seasons,” the blind writer explained how he cooked in his Greenwich Village kitchen by touching, smelling, and listening. “Small sounds from the oven hitherto unnoticed suddenly become imperative and indicative,” he said. He told Claiborne that the biggest obstacle was overcoming a fear of knives.

Petra Chu, a professor emerita at Seton Hall University, was a graduate student of art history at Columbia in 1967, when she began working as an assistant for de Groot at his home office in the West Village. “He coped with it incredibly well,” she said of his blindness, “but you knew that this was not something that was easy for him, at all. Maybe that’s why his descriptions are sometimes a little over the top. He was heightening everything.” His father was a Dutch painter who was friends with Piet Mondrian. Fiona Rhodes, de Groot’s daughter, told me that “the thing he missed most about not being sighted was not being able to look at art.”

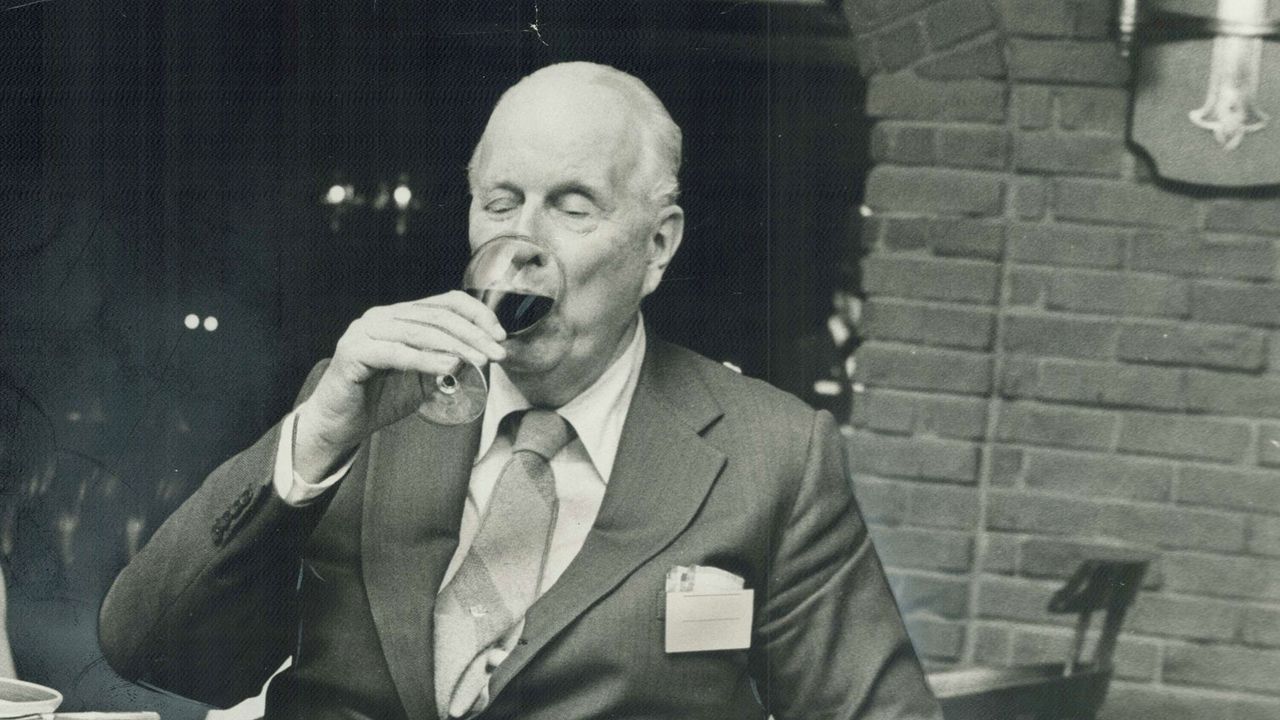

Chu and another young assistant, Bonnie Messenger, were with de Groot and his service dog, Nusta, on the fateful trip to France in 1968. He was reporting two stories. The first, “A Weekend of Incredible Gluttony,” published in Esquire, is a survey of the restaurant scene in Lyon, composed with the glib swagger of mid-century men’s magazines: he characterizes the city as a place where “everything smells deliciously of crackly crisp money and pink sauce Choron.” (In this story, too, his blindness goes unmentioned.) De Groot tasted his way through lavish meals, with Chu and Messenger describing the visuals into his tape recorder. “We had to tick the clock—if the plate was arranged, we had to describe where everything was: this is at twelve o’clock, this is at three o’clock,” Chu, now eighty-two, recalled. “When he wrote what I had described, it was all in Technicolor.”

Their second story, intended for Venture, a travel magazine, was about Chartreuse—the piece that brought the trio to the inn. But they didn’t spend much time there, in Chu’s recollection. “Maybe once or twice we had the lunch,” she said. “And maybe we had one or two dinners. He made a lot of stuff up.” The food was delicious, Chu said, though the inn itself was more basic than de Groot described. In photos that Chu and her husband took in 1971, her first and only time back, the dining room appears spartan and comfortless. But the idyllic natural scenery was real, as were Artaud and Girard, the inn’s charismatic proprietors. “I used to call them Gertrude Stein and Alice B. Toklas,” Chu said affectionately.

De Groot began to pitch the cookbook a few months after he returned from France. In January, 1969, he told his agent, Oliver Swan, that he’d floated the idea on the phone to Knopf’s Judith Jones, who had edited “Feasts for All Seasons.” “The great strength of this little book,” he told Swan, “would be its total reality.” Jones, who had perfected the technique-wired cookbook early in her career, with Julia Child’s “Mastering the Art of French Cooking,” was unpersuaded. “I’m afraid I can’t make a sound editorial judgment until Roy can show me the range and quality of the recipes,” she told Swan, a month later. “If that isn’t possible until he makes another trip back to the auberge, then, frankly, I would work on magazine support for the idea at this point.”

But it’s unlikely that de Groot ever returned to the auberge. Travel could be costly and difficult for him, and he sometimes found navigating unfamiliar places like toilets humiliating. By summer, he and Swan were still trying to sell Jones on the book that she called—possibly disdainfully—the “Auberge of the Flowering Chimneys.” The recipes still hadn’t materialized. “I may be wrong,” she told Swan in a rejection letter, “but I would hate to enter into a project that I had reservations about,” especially since de Groot had proved difficult to work with on “Feasts for All Seasons.” After at least two more publishers passed on the book, Bobbs-Merrill offered a contract.