Observations

Circinus was observed (ID: 4611; PI: Lopez-Rodriguez, E.) on 20240715 and 20250427 using the Aperture Masking Interferometry [AMI;32] mode of the Near Infrared Imager and Slitless Spectrograph [NIRISS;33] instrument on the JWST. We performed observations of Circinus and a standard star, HD119164, using the F380M (λc = 3.827 μm, Δλ = 0.21 μm), F430M (λc = 4.326 μm, Δλ = 0.20 μm), and F480M (λc = 4.817 μm, Δλ = 0.30 μm) filters. For all observations, the AMI pupil mask (Supplementary Fig. 1), the SUB80 (80 × 80 px2) array, and the NISRAPID readout pattern were used with a pixel scale of 65 mas px−1 and a readout of 75.44 ms. To avoid signal limit (26,000 e−) of the standard star during the observations, we used a setup with 145, 338, and 190 integrations and 4, 4, and 5 groups in the filter sequence of F480M, F380M, and F430M, respectively. This sequence is used to optimize the direction of rotation of the filter wheel and prolong the life of the mechanism. For both Circinus and standard star, the total/effective exposure times are 102/76 s, 57/72 s, and 44/33 s in the F380M, F430M, and F480M filters, respectively. The Stare mode without a dither pattern was used. These are the first two observations of a set of three from this JWST program to rotate the uv-plane of the observations. The V3 position angles are 4° and 87° for the first and second epoch of observations. The uv-plane has rotated by 87°−4° = 83° (Supplementary Fig. 1), which agrees with the 90° with a 10° margin offset between both epochs requested for these observations.

Data Reduction

We processed the NIRISS AMI observations using the JWST Calibration pipeline (version 1.15.1; CRDS version 11.17.26) and the CRDS context jwst_1258.pmap. We followed the standard NIRISS AMI data reduction recipe for stages 1 to 4. Stage 1 (calwebb_detector1) produces corrected count rate images (‘rate’ and ‘rateints’ files) after performing several detector-level corrections. Stage 2 (calwebb_image2) produces calibrated exposures (‘cal’ and ‘calints’ files), where we skip the photometric calibration (photo = False) and resampling (resample = False) of images. These steps produce the interferogram image in units of digital counts shown in Supplementary Fig. 1. Stage 3 (ami_analyze) is a specific pipeline step for the AMI observations. This step produces the interferometric observables (‘ami-oi’ files) after computing fringe parameters for each exposure producing an average fringe result of the full observations. The uv coverages of the observations for both epochs are shown in Supplementary Fig. 1. Stage 4 (ami_normalize) produces (‘amimorn-oi’ files) the final normalized interferometric observables after correcting the science target using the reference standard star. The normalized and calibrated visibilities, V2, and closure phases for both epochs are shown in Supplementary Fig. 2.

Additionally, we obtained calibrated interferometric observables using SAMPip51. This software uses a fringe-fitting routine to look for the amplitude and phase solutions that recover the structure of the interferogram, considering the non-redundant mask geometry of NIRISS/JWST. Each frame in the data cubes is fitted individually, and the final squared visibilities and closure phase values are averaged per data cube with their corresponding standard deviations. The observables from the science data cubes are corrected by the instrumental transfer function using the standard star HD 119164. The calibrated observables are stored in standard OIFITS files52 for posterior analysis.

Image reconstruction

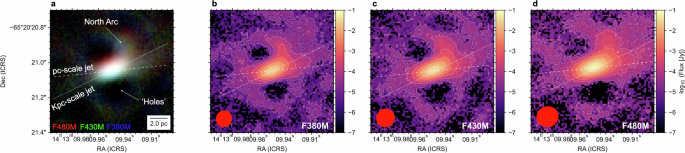

We reconstructed the Circinus images at each filter using SQUEEZE (GitHub repository of SQUEEZE: https://github.com/fabienbaron/squeeze) [version 2.7;36]. This algorithm has successfully been used to reconstruct the NIRISS AMI observations of the Wolf-Rayet, WR 13753. SQUEEZE reconstruction image algorithm uses a Markov Chain Monte-Carlo (MCMC) approach to explore the imaging probability space using the interferometric observables with its associated uncertainties. Using the SAMPip outputs, SQUEEZE images were recovered using a pixel grid of 129 × 129 px2 (FOV = 1.29 × 1.29 arcsec2), with a pixel scale of 10 mas. For the reconstruction, we used two regularization functions, a Laplacian and the L0-norm, with the following hyperparameter values μLa = 500 and μL0 = 0.2, respectively. With these parameters, the reconstructions converged with \({\chi }_{\nu }^{2}\) close to unity. To characterize the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) of the images, we recovered 100 images per data cube with different samples of the observed uv-plane. For this procedure, we randomly sampled the uv frequencies of the interferometer by changing their weights; at the same time, we kept the total number of uv points constant. Each image is the result of the MCMC from SQUEEZE from a random sample of the uv plane with a specific uv weight. Finally, we averaged the 100 different reconstructions per wavelength to construct the final image. We computed the dirty beam of each filter shown in Supplementary Fig. 3. The angular resolutions in the reconstructed images of Circinus are 93 × 88 mas2 (1.9 × 1.8 pc2), 105 × 101 mas2 (2.1 × 2.0 pc2), and 123 × 116 mas2 (2.5 × 2.3 pc2) in the F380M, F430M, and F480M filters, respectively, which corresponds to the theoretical angular resolution of λ/2B by the interferometric observations.

To estimate the validity of the reconstructed images compared with the calibrated observables, we computed the synthetic interferometric observables from each one of the recovered images per wavelength. The mean value and the standard deviation of the synthetic observables are shown in Supplementary Fig. 4. It can be observed that all data points from the images are consistent with the data within 1σ. Similarly, to estimate the statistically significant features with SNR above the noise level in the images, we estimated their noise statistics (μnoise, σnoise) using all the pixels values outside a box of 40 × 40 px2 (8 × 8 pc2) centered in the image. The interferometric observables of those filtered images are consistent within 1σ of the reported synthetic observables, allowing us to trust the significance of the recovered morphology.

WCS correction

The reconstructed images do not have a world coordinate system (WCS) associated with them. However, the interferogram pattern (Supplementary Fig. 1) has the WCS from the JWST observations. Thus, we use the sky coordinates of the peak from the interferogram pattern as the sky coordinates of the peak pixel from the reconstructed images at each filter. Here, we assume that the peak pixel of the reconstructed image is the position of the AGN, which dominates the IR emission of the object in both the interferogram pattern and the reconstructed images. A small WCS shift was then performed to align the AMI/JWST observations with the peak emission of the 1200 μm ALMA observations (Fig. 2). The 1200 μm ALMA observations trace the radio synchrotron emission from the jet and AGN, we assume this is the ‘true’ center of the AGN in our work.

Flux calibration

The standard star HD119164 (F12 μm = 1.2 Jy) was observed immediately after the science object using the same configuration as that for the Circinus galaxy. We took observations of the same standard star as previously used by the interferometric observations of Circinus with MATISSE/VLTI at L, M, and N-bands27,29. The standard star serves to perform the flux calibration and final visibilities of the science object. The flux calibration of the final reconstructed image of the science object was computed as:

$${F}_{{{{\rm{obj}}}}}^{{{{\rm{cal}}}}}(\lambda )\,[{{{\rm{Jy}}}}]={F}_{{{{\rm{obj}}}}}^{{{{\rm{norm}}}}}(\lambda )\times \frac{{F}_{\star }(\lambda )\,[{{{\rm{Jy}}}}]}{{F}_{\star }^{{{{\rm{T}}}}}(u=0,v=0,\lambda )\,[{{{\rm{ADU}}}}]}\times {F}_{{{{\rm{obj}}}}}^{{{{\rm{T}}}}}(u=0,v=0,\lambda )\,[{{{\rm{ADU}}}}],$$

(1)

where \({F}_{{{{\rm{obj}}}}}^{{{{\rm{norm}}}}}(\lambda )\) is the normalized reconstructed image of the science object with a total flux equal to unity, F⋆(λ) is the total flux of the standard star in units of Jy, \({{{{\rm{F}}}}}_{\star }^{{{{\rm{T}}}}}(u=0,v=0,\lambda )\) is the total flux of the zero-baseline of the standard star in units of counts (i.e., ADU: analog digital unit), and \({{{{\rm{F}}}}}_{{{{\rm{obj}}}}}^{{{{\rm{T}}}}}(u=0,v=0,\lambda )\) is the total flux of the zero-baseline of the science object in units of counts (i.e., ADU). All these fluxes are at a given wavelength, λ.

F⋆(λ) was estimated using the spectral type, G8II, of the standard star, scaled to have a flux of 1.2 Jy at 12 μm27,29. Then, we estimated the total flux of the standard star within the bandpass (The NIRISS throughputs can be found at https://jwst-docs.stsci.edu/jwst-near-infrared-imager-and-slitless-spectrograph/niriss-instrumentation/niriss-filters#NIRISSFilters-NIRISSsystemthroughput) of the NIRISS/AMI filters to be 8.55, 7.09, and 5.95 Jy at F380M, F430M, and F480M, respectively. \({F}_{\star }^{{{{\rm{T}}}}}(u=0,v=0,\lambda )\) was estimated using the total flux of zero-baseline from the image of the mirrored Hermitian counterparts in this uv-plane coverage, or Modulation Transfer Function [MTF; see Fig. 1 by ref. 32]. The zero-baseline contains the total flux of the observations. We computed the total flux from the central peak of the MTF image using two methods. First, we perform aperture photometry with a radius of 3.5 pixels. Second, we fit a 2D Gaussian profile with two free parameters: the amplitude and the FWHM, which is assumed to be axisymmetric. We estimate that the aperture photometry (i.e., first method) misses about 12–22% of the flux arising from the wings of the 2D Gaussian profile. We use the total flux of the zero-baseline estimated with the 2D Gaussian fitting profile. NIRISS AMI mode has a photometric calibration uncertainty (NIRISS AMI photometric calibration: https://jwst-docs.stsci.edu/depreciated-jdox-articles/jwst-data-calibration-considerations/jwst-calibration-uncertainties#JWSTCalibrationUncertainties-Photometriccalibration.10) of 5% in the F380M and F430M filters and 8% in the F480M filter.

Emission line contribution

To estimate the potential contribution of spectral features within the filters, we use synthetic photometry on both the observed spectra and the feature-free continuum spectra of local AGN. First, we establish a baseline representing the continuum emission from the central spectrum by fitting feature-free continuum anchor points with straight lines [e.g.,54]. Using the fitted baseline, we then perform synthetic photometry for the NIRISS imaging bands by convolving the spectra with the corresponding filter transmission curves (http://svo2.cab.inta-csic.es/svo/theory/fps/index.php?mode=browse&gname=JWST&gname2=NIRISS&asttype=, as in ref. 55 (see also Donnelly et al.56). The main features contributing to the F380M, F430M, and F480M filters include gas-phase and icy molecular bands such as the 12CO (4.45 − 4.95 μm) molecular gas-phase absorption band and the 4.27 μm stretching mode of the CO2 ice [e.g.,54,57,58]. We utilize local AGN (NGC 3256 and NGC 7469) observed with MRS/JWST from the Director’s Discretionary Early Release Science Program #1328 (PIs: L. Armus & A. Evans) to calculate the fractional contribution of the continuum to the photometry of type 1 and type 2 AGN. For type 2 AGN, we find a continuum contribution of 94%, 71%, and 84% in the F380M, F430M, and F480M filters, respectively. Note that these continuum contributions should be considered a lower limit, as the lines are known to be stronger in luminous IR galaxies, such as NGC 3256, which was used in this estimation. In the case of the type 1 NGC 7469, the continuum dominated the emission in all the filters used in this work.

Archival observations

For our imaging analysis, we use the following archival observations. NACO/VLT images at L’-band (3.8 μm, Δλ = 0.62 μm) with an FWHM of 0.12”28. VISIR/VLT at N-band (10.5 μm; Δλ = 0.01 μm) with an FWHM of 0.3”30. MATISSE/VLTI at 12.0 μm with an FWHM of 10 mas29. Dust continuum emission at 700 μm and non-thermal emission at 1200 μm using ALMA with beam sizes of 107 × 64 mas2 at a PA = 74° and 27 × 24 mas2 and PA = 15°, respectively25. Dust and radio continuum emission at 890 μm with a beam size of 100 × 80 mas2 and PA = −1. 7° (ALMA ID 2022.1.00222.S), [CI] 3P1-0P1 with a beam size of 119 × 76 mas2 and PA = 75°, H36α with a beam size of 62 × 43 mas2 and PA = −8°, and HCN(3-2) with a beam size of 29 × 24 mas° and PA = 20° 25. CO(6-5) with a beam size of 95 × 66 mas2 and PA = 34° 40.

Photometry

We perform photometric measurements using a circular aperture and an elongated 2D Gaussian. We compute circular aperture photometry with (a) a diameter equal to the FWHM at each wavelength, (b) a fixed aperture equal to the lowest resolution of our observations, i.e., 123 mas (2.5 pc at 4.8 μm), and c) a fixed aperture encompassing the full extended emission of the Circinus, e.g., 640 mas (12.3 pc). In addition, to optimize the extraction of the fluxes from the elongated emission, we performed photometric measurements using a 2D Gaussian profile. The 2D Gaussian profiles are fixed at the location of the peak pixel at each wavelength and have four free parameters: the x and y axes of the FWHM, the PA, and the total amplitude of the peak of the 2D Gaussian profile. We computed a Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) approach using the No-U-Turn Sampler [NUTS;59] method in the python code pymc360. We set flat prior distributions within the ranges of x = y = [0, 3] × FWHM at a given wavelength, \(\theta={\left[0,180\right)}^{\circ }\) East of North, and I0 = [0, 1] (peak has been normalized to unity). We run the code using 5 chains with 5,000 steps and a 1000 burn-in per chain, which provides 20,000 steps for the full MCMC code useful for data analysis. Supplementary Fig. 5 shows the best fits of the 2D Gaussian models per wavelength and the residuals. Supplementary Table 1 shows the photometric measurements of all the methods described above.

SED

We took the 1−20 μm SED with apertures of 0.1–0.4″ used by Stalevski et al.30, and added the 3.8−4.8 μm AMI/JWST photometric points from our analysis (Supplementary Table 1), and the photometric measurements of the central 123 mas using the 700−1200 μm ALMA observations shown in Fig. 2. The 1−1000 μm SED is shown in Fig. 3, and in Supplementary Figs. 6, and 7. To estimate the relative contribution of non-thermal synchrotron emission at 700 μm, we use the radio observations from 3 to 20 cm observed by the Australia Telescope Compact Array (ATCA)61. We estimate that the non-thermal synchrotron emission at 700 μm contributes <50%. Note that the ATCA data have a low angular resolution 20”, compared to the 100 mas resolution from the ALMA observations. Thus, this relative contribution is an overestimated upper-limit to the synchrotron emission at 700 μm.

Torus models

We took four torus models comprising several geometries with the main goal of distinguishing between a disk-like or wind-like structure20,62. For all models, we fixed the inclination of the disk to be edge-on, i = 90°, and let the dust screen be a free parameter, E(B-V).

Smooth41 torus model uses a torus-like geometry with a smooth dust distribution. The torus parameters are: i is the viewing angle toward the torus, σ is the half opening angle of the torus, γ and β are the exponents of the logarithmic azimuthal and radial density distributions, respectively, Y = Ro/Ri is the ratio between the outer and inner radii of the torus, and τV is the edge-on optical depth at 0.55 μm.

clumpy42,43 torus model uses a clumpy distribution distributed in a torus-like structure. The free parameters are: i is the viewing angle toward the torus, N0 is the mean number of clouds radially across the equatorial plane, σ is the half opening angle of the torus width measured from the equatorial plane, Y = Ro/Ri is the ratio between the outer and inner radii of the torus, q is the slope of the radial density distribution, and τV is the optical depth at 0.55 μm of individual clouds.

2-phase clumpy44 torus model uses a torus geometry with high-density clumps and low-density, and a smooth interclump dust component. The free parameters are: i is the viewing angle toward the torus, σ is the half opening angle of the torus, p and q are the indices that set the dust density distributions along the radial and polar directions, respectively, Y = Ro/Ri is the ratio between the outer and inner radii of the torus, τV is the average edge-on optical depth at 0.55 μm, and maximum dust grain sizes, \({P}_{{{{\rm{size,max}}}}}\). The extinction by dust grains was taken from ref. 63 and website https://heasarc.gsfc.nasa.gov/xanadu/xspec/manual/node291.html.

CAT3D-WIND45 torus model uses a clumpy disk and a dusty polar outflow. The free parameters are: i is the viewing angle toward the torus, N0 is the number of clouds along the equatorial plane, a is the exponent of the radial distribution of clouds in the disk, θ is the half-opening angle of the dusty wind, σθ is the angular width of the hollow dusty wind cone, aw is the index of the dust cloud distribution power-law along the dusty wind, h is the height of the inner edge of the torus, and fwd is the wind-to-disk ratio.

We fit each of the torus models to the 1–1000 μm SED with and without the AMI/JWST photometric measurements (Supplementary Fig. 7). We use the same fitting routine described in González-Martín et al.62, which uses a χ2 minimization approach. The model parameters and 1σ uncertainties associated with the best-fit model are shown in supplementary Table 2. We estimate the χ2 of the models within the 1–1000 μm SED, \({\chi }_{ALL}^{2}\) and within the 1–20 μm SED, \({\chi }_{IR}^{2}\).

We estimate the dust mass of the two favored torus models: clumpy and 2-phase torus using the best-fit parameters of the fixed aperture (123 mas; 2.5 pc). The median dust masses are \(\log ({M}_{{{{\rm{dust}}}}}[{M}_{\odot }])=3.61\) and \(\log ({M}_{{{{\rm{dust}}}}}[{M}_{\odot }])=3.74\) for the clumpy and 2phase models, respectively. For the clumpy torus modes, σ and Y are upper limits, so the maximum torus mass is \(\log ({M}_{{{{\rm{dust}}}}}[{M}_{\odot }])=4.61\). For the 2-phase torus model, we have a lower-limit for p > 1.3 and an upper limit for q < 1.5. Using both limits, we estimate a mass range of \(\log ({M}_{{{{\rm{dust}}}}}[{M}_{\odot }])=3.38-5.54\). Note that in all cases q is at the upper-bound of its range, which indicates that the torus has its mass mainly concentrated on the inner side of the torus (i.e., radial distribution of clouds: r−q, where r is the radial distance). For comparison, the molecular masses of the torus are estimated to have a median of \(\log ({M}_{{{{\rm{dust}}}}}[{M}_{\odot }])=5.77\)64. This mass is estimated using CO observations using ALMA of nearby AGN with higher bolometric luminosities \(\log ({L}_{{{{\rm{bol}}}}}[{{{\rm{erg{s}}}^{-1}}}])=44.0\) than the Circinus galaxy \(\log ({L}_{{{{\rm{bol}}}}}[{{{\rm{erg{s}}}^{-1}}}])=43.6\). Lower dust mass is expected in the torus of Circinus.

HyperCAT

The emergent thermal emission as a function of wavelength for the best fit of the clumpy torus model at the native resolution (1.2 mas) of the model is shown in Supplementary Fig. 8. Note that the thermal emission distribution changes as a function of wavelength. At 4.3 μm and 10 μm the emission is along the funnel of the torus, while the 700 μm thermal emission is along the equatorial axis of the torus. At all wavelengths, the emission drops at the core due to the column density along the LOS, and the emission peaks at the inner walls of the torus, directly radiated by the AGN and directly viewed by the observer LOS.