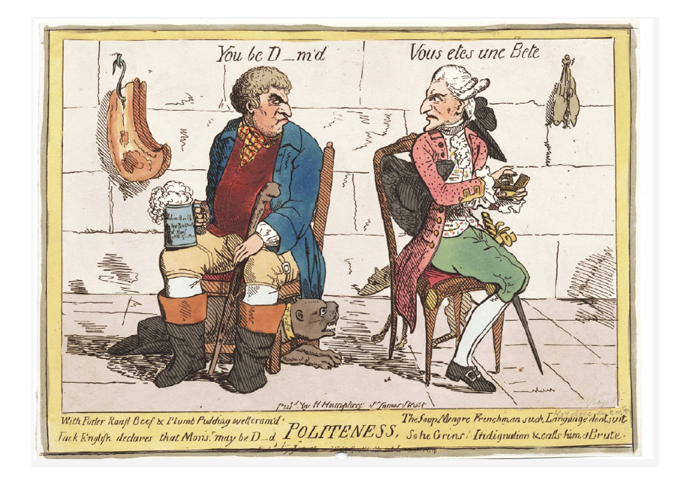

James Gillray’s Politeness,1779 [Lewis Walpole Library]

IN Paris, journalist Louis-Sebastien Mercier wrote: “They imagine a Frenchman could not cross the street in London without being insulted, that every Englishman is fierce and devours raw flesh. In London, they think that all Frenchmen are thin, flat-stomached, carry a large purse, a long sword and that they live on nothing but frogs.”

That was one of the many observations the writer made while enjoying a spring excursion in London in 1780: and now, the manuscript he produced from the trip is being published for the first time in English.

Islington-based publisher Pallas Athene has produced Neighbours and Rivals, an Eighteenth Century Journey Between Paris and London, put together by history professors Laurent Turcot and Jonathan Conlin.

It reveals Mercier was part of a new journalism growing in the build-up to the French Revolution.

“A new form of urban literary discourse emerged, which broke with the rigid and by then somewhat hackneyed conventions of travelogue,” say the authors. “Mercier became one of the most important representatives of this shift away from antiquarian and topographical approaches, which treated the city as a collection of monuments, to more reflexive, journalistic and emotive representations of the city as a collection of experiences, habits and personalities.”

Mercier was born in Paris in 1740, the son of a sword cutter.

He would boast of a literary childhood, and as a teenager, he soaked up Parisian culture.

His first break came with his novel, Memoirs of the Year 2440 – a precursor to the utopian sci-fi, which also saw him turn the pre-Revolution ancien régime into a figure of satire.

He wrote plays and edited the Journales des Dames, which he packed with observations of city life.

“For Mercier, the city was much more than a convenient framework in which to recount witty anecdotes to satisfy cravings for novelties,” they add.

“His project was to capture the essence by laying bare its inner workings and liaisons which kept its countless parts in incessant movement.”

It was the spring of 1780 he embarked to London. His stay lasted months.

In the opening, Mercier says: “The two capitals are so close and so different, yet bear so strong a resemblance to each other that my study of Paris would be incomplete were I not to consider some aspects of the other.”

Mercier says Paris’s river has well-built quays, which means “The Seine is a beautiful woman who disports herself leisurely. The Thames is a hardworking mother with a great many children… her happy position close to the Channel makes her mistress of the seas. Her position secures her freedom by means of a strong navy, while her maritime trade means she feels a closer connection to all countries than she does to Paris.”

Mercier’s eye reveals wonderful clichés:

He claims: “The English national character seems less scatterbrained than the French. This composure has become so prevalent, after so many civil wars, that the precious hard-won right to meddle in the affairs of state as well as the need to guard that right vigilantly has been imprinted on their minds.”

He finds a city which welcomes immigrants.

“The people are partly made up of sailors, or of people whose ancestors hailed from distant maritime countries.”

He compares food – citing how the French seem to live on soup “over-stewed… hard to digest… spicy sauces, seasoned fricassees…” compared to London: “roast meat is consumed everywhere. Potatoes are boiled and generally speaking sauces are scarcely to be found”.

He considers how capital punishment is approached, how relief for the poor is managed, and banking systems.

Mercier compares everything from balls to how horses are treated: “The English take their humane feelings for horses to extremes, he adds. “Whoever unjustly or brutally mistreats his horse in public is liable to be seized and mistreated himself.”

Mercier’s work reveals a London recognisable today – his journalist’s eye captured the city and offers a stylised vision of what a metropolis could be.

They say he used a small notebook called a carnet to scribble down his impressions and then polished the work up when he returned to Paris.

“The state of the manuscript reproduced here certainly suggests it was the product of careful thought, rather than a series of notes made on the spot,” they state.

But the manuscript lay unpublished until 1982 – while this edition by Pallas Athene is the first time his worlds have been translated and published in English.

It was never published in his lifetime – “even at a time of Anglomania in France, Mercier may have judged this text to be too Anglophile,” they consider.

“Or else his enthusiasm for the larger project simply overlooks its progenitor.”

The larger project was a two-volume “tableau” that considered looking at London as a way of considering his home city with fresh eyes.

Mercier’s works reflects a growing sense of a relationship between the two cities, which became “more striking and numerous” to contemporaries in the latter stages of the 18th century, the authors state.

Writers no longer sized up both cities and accentuated the differences for the reader’s mirth and curiosity: instead, writers began to emphasise similarities and areas that showed mutual emulation, and ways both cities could improve.

They cite books by John Andrews and John Moores in English and Pidansat de Mairobert and Jean-Jacques Rutlidge as authors who tried to illuminate each other’s capitals for mass readership.

Mercier wanted to find the best elements to highlight how capital living could be improved.

“His version of London is, in fact, a projection of his philosophical imagination – not simply a rounded portrait of the British capital but also a reflection of what Mercier hoped Paris could become,” they say.

The Grand Tour took hold in the same century, sending British aristos through Paris and then beyond: but by the time Mercier made the journey in the other direction, to and fro journeys were more commonplace: “during the course of the century such exchanges ceased to be an aristocratic appendage,” the book says.

“Individuals of middling rank, among them merchants, officers, artists and even some skilled labourers also took the road.

“They read travelogues and guides, adding their own marginalia as they travelled or in some cases writing their own manuscripts travel diaries.”

Mercier offered a wide-eyed approach, curious about all he came across – and his book today sheds light on a key period of London life.

• Neighbours and Royals: An Eighteenth-Century Journey Between London and Paris. By Louis Sebastien Mercier, Pallas Athene, £24.99

pallasathene.co.uk/mercier