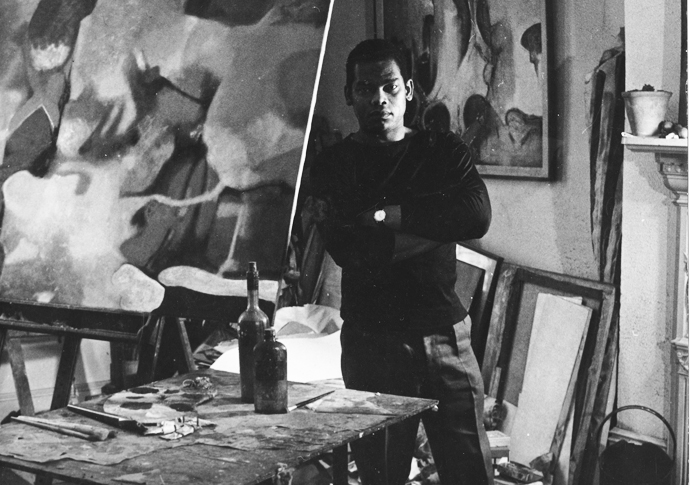

Aubrey Williams, circa 1961, in his studio at Greencroft Gardens (detail). [Courtesy Estate of Aubrey Williams]

TODAY considered one of the most important artists of the 20th century, Aubrey Williams always thought outside the box and defied easy categorisation. The results are the startling canvasses currently on show at the October Gallery, hard to fathom but holding your gaze with their drama and colour.

Aptly titled Elemental Force, it is Williams’ eighth solo exhibition at the Bloomsbury-based gallery, whose championship of his work over the past four decades has helped see his star dramatically rise in recent years, with a show last year at Tate Britain.

“For years, Aubrey’s work wasn’t recognised properly and it is only now people are realising how stunning an artist he was,” said the October’s director Chili Hawes.

On display are a variety of pieces from the 1950s through to the 1980s, including work that has never been seen before, paintings that are now considered ahead of their time in their abstract depiction of Williams’ piercing “cosmosvision”.

He arrived in the UK from Guyana in 1952 aged 26 to become a professional artist, developing a highly distinctive practice that drew chiefly on his passion for pre-Columbian art but also American abstract expressionists like Jackson Pollack, Mark Rothko and Arshile Gorky, and the music of Russian composer Dimitri Shostakovich.

A prolific painter, he worked out of studios at his home in Greencroft Gardens, West Hampstead, where he lived with his wife and daughter, and also frequently undertook artistic expeditions to Guyana, Jamaica and the US. But in England he came up against an antipathy towards abstract art and art considered to be outside the Western canon and, after moderate success in the 1950s and 1960s with a number of small exhibitions, struggled to find a larger platform. To help pay the bills, he taught at Exeter University and the Camden Arts Centre.

“The situation is England was dire – there was so much prejudice against work that wasn’t European,” said Hawes, who co-founded the October Gallery in 1979 to breech such cultural insularity. “There was just the Commonwealth Institute and Africa Centre. People came to us because there was nowhere else to go.”

After Williams’ death from cancer in 1990 his work faded from view. “We formed a committee to discuss how we can progress Aubrey’s work so that it gets greater public attention,” added Hawes.

“We saw that he was really a great artist and we needed to do everything we could to get him more exposure. We banged on a lot of doors and pushed for Tate Britain to take a look at his work. In the end [in 2023-2024], it dedicated a whole room to him in recognition of his contribution to 20th century British art.”

Aubrey Williams: Quartet No 5, Opus 92 (Shostakovich Series), 1981 oil on canvas,132 x 208cm. © Estate of Aubrey Williams. Courtesy the Estate of Aubrey Williams and October Gallery. [©Jonathan Greet]

Williams was born into a middle-class family in Georgetown and proved artistically gifted early on, joining the pioneering Working People’s Art Class at the age of 12. However, at his father’s behest, he trained as an agronomist, becoming an official responsible for increasing sugar production. But his efforts to improve the lot of sugar cane workers instead led to him being effectively banished to the remote north-west, Guyana’s equivalent to Siberia, to work with the Warrau, one of the Amerindian tribes that populate the country’s vast Amazonian interior.

In Imruh Bakari’s fascinating 1987 documentary, Mark of the Hand, which is to be shown as part of a series of events accompanying the exhibition, Williams reveals that it was his accidental encounter with the Warrau, their artefacts and rituals, that would prove life-changing, saying, “In a sense, I didn’t really discover art until I got to know the Warrau Indians.”

Thereafter, much of his work came to incorporate pre-Columbian iconography that he came across during his two years in the bush, to express not only his profound reverence for nature but his fears about its destruction, using the spectacular collapse of the Mayan civilisation – as alluded to in his painting Time and the Elements (Olmec-Maya and now) – to show what happens when technology gets ahead of itself and destroys the environment that gave rise to it. “We are doing the same thing today. We are fast running behind our technology,” he said, long before the word “ecocide” had entered public consciousness.

In the film, which was shot in Guyana, we see him lovingly restoring the totemic murals he painted at the former Timehri International Airport in 1970 on behalf of the government which, on paper at least, also considered Amerindian culture an important part of the national story. “Timehri” means “mark of the hand” in Arawak – in other words, “art” – and forms the title of several of his works.

Later, in an emotional return to the Warrau village he once stayed in, and surrounded by jungle foliage, he talks of his love of Shostakovich, which produced a series of related paintings, among them the thrilling Quartet No 5, Opus 92: “The first time I heard his first symphony I was in my early teens and this music hit me, it hit me really hard because I was hearing for the first time a total sound of music that had rather profound visual connotations. I could feel colour.”

For Williams, the cosmos has no borders or distinctions and, by the same token, neither has art.

• Aubrey Williams: Elemental Force at October Gallery, Old Gloucester Street, WC1N 3AL, runs until July 26, Tues-Sat, free. The screening of Mark of the Hand takes place at 6.30pm, Wed, July 2 (free but booking required) octobergallery.co.uk/events/