Study populations

All contributing cohorts (UKB, CKB and NHS) received ethical approval from their respective institutional review boards, and all participants consented to the use of their anonymized information for research purposes at the time of recruitment. All participants from the UKB and CKB provided written informed consent. In the NHS, institutional review boards approved questionnaire completion as implied consent.

The UKB is a prospective population-based cohort of more than 500,000 individuals aged 40–70 years who were recruited between 2006 and 2010 from the UK general population, with deep phenotyping and genomic data available67. Participants were followed up through data linkage to electronic health and medical records, including national primary and secondary care, as well as disease and mortality registries68, with validated reliability, accuracy and completeness69. Additional online surveys were conducted to facilitate the follow-up of cognitive and symptom-based mental well-being outcomes. In the current study, we included a subset of randomly selected, representative UKB participants with Olink proteomics data available at baseline (n = 46,785).

The CKB is a prospective cohort study of 512,724 adults aged 30–79 years who were recruited from ten geographically diverse (five rural and five urban) areas across China during 2004 to 2008 (ref. 70). We included CKB participants with baseline Olink data in a nested case–cohort study of ischemic heart disease and who were not genetically related (n = 3,977).

The NHS is a prospective cohort study involving 121,700 female registered nurses from 11 US states, aged 30–55 years at enrollment in 1976, with follow-up data collected using biennial questionnaires71. Between 1989 and 1990, a total of 32,825 participants provided blood samples. We included NHS participants with Olink data in a prospectively designed nested case–cohort study of colon cancer (n = 800).

Proteomic profiling

Proteomic profiling of baseline blood plasma samples was conducted for all three cohorts using the same Olink Explore 3072 assay, which includes four panels (cardiometabolic, inflammation, neurology and oncology) measuring 2,923 independent proteins. Among 54,219 UKB participants with available Olink data, we included 46,673 individuals who were randomly selected and shown to be highly representative of the broader UKB population72, excluding those manually selected for disease enrichment. In the UKB, no effects of batch and plate, or abnormalities in the protein coefficients of variation, were observed. The interplate and intraplate coefficients of variation for all Olink panels were lower than 20% and 10%, respectively, with a median of 6.7% (ref. 72). High correlations were observed for the same proteins across panels and between the Olink assay and independent assays. Details of Olink proteomic measurements, data processing and quality control in the UKB are described in the online document (https://biobank.ndph.ox.ac.uk/showcase/label.cgi?id=1839) and published work72. Details of proteomic profiling in the CKB and NHS are provided in Supplementary Notes 5 and 6. Proteomics data across all cohorts were provided as normalized protein expression values on a log2 scale. We excluded seven proteins that were missing in more than 20% of UKB participants (GLIPR1, NPM1, PCOLCE, CST1, CTSS, TACSTD2 and ENDOU). Participants with more than 50% missing proteins were further excluded. The final UKB dataset included 43,616 participants and 2,916 proteins. Normalized protein expression data were rescaled to range between 0 and 1 and then centered on the median.

Organ-specific protein mapping

Organ-enriched genes and plasma proteins were determined using human organ bulk RNA-seq data from the GTEx project (v8; 54 tissue types)11 and were validated using data from the Human Protein Atlas (HPA)73 (Extended Data Fig. 1 and Supplementary Tables 1–3). Genes were defined as organ-enriched when their expression was at least fourfold higher in one organ than in any other, following the HPA criteria validated in previous studies3. In GTEx, tissues were initially mapped to corresponding organs based on physiological function3, and organ-level gene expression was established by identifying the maximum expression value among its tissue subtypes. Identified organ-enriched genes were further tested using the same criteria in the HPA tissue-level data. We annotated the 2,916 plasma proteins measured by the Olink panel with this information.

Disease, biomarker and age-related phenotypes

In the UKB, the primary disease outcomes are major NDs, such as ACD, VD, AD, PD, MS and psychiatric diseases, including psychotic disorders, mood disorders, anxiety disorders, sleep disorders and substance use disorders. For psychiatric diseases, we assessed the major subtype in each category separately (for example, schizophrenia in psychotic disorders, depression in mood disorders and generalized anxiety disorder in anxiety disorders). Incident disease diagnoses were ascertained using International Classification of Diseases (ICD) codes from linked hospital inpatient, primary care (with read codes transformed into ICD codes) and death registry data. Self-reported cases were not considered to ensure the reliability of the diagnosis, but they were used to identify and exclude participants with relevant prevalent diseases. For comparison, we also included major chronic physical diseases directly relevant to specific organs, including hypertension, myocardial infarction, stroke, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, CKD, chronic liver disease and T2D. Detailed definitions of disease outcomes are provided in Supplementary Table 12. For additional benchmarking, we included all-cause mortality, which was ascertained through linkage to the national death registry. Details of the mapping process for incident disease outcomes are available online (https://biobank.ctsu.ox.ac.uk/crystal/refer.cgi?id=593).

Other phenotypes of interest included biomarkers (blood chemistry, blood count, nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) metabolites and neurobiomarkers), as well as age-related physiological, cognitive and mental well-being conditions available among participants with proteomic data. Detailed definitions of these phenotypes are provided in Supplementary Table 13.

Blood chemistry markers and blood counts were measured using nonfasting serum samples from all participants at baseline. Biochemical measures were adjusted for technical variation, with details of sample processing (https://biobank.ndph.ox.ac.uk/showcase/showcase/docs/serum_biochemistry.pdf) and quality control (https://biobank.ndph.ox.ac.uk/showcase/ukb/docs/biomarker_issues.pdf) provided online. A total of 30 biochemistry markers (related to liver and renal function, endocrine status and immunometabolism) and 31 blood cell counts (including white blood cells, red blood cells and platelets) were used.

NMR metabolites were measured using baseline plasma samples from approximately one third of randomly selected participants (n = 118,461) in the UKB, including absolute concentrations of 168 biomarkers (81% are lipids and lipoprotein subfractions) along with 81 ratios of these biomarkers. Details of sample processing and quality control are available online (https://biobank.ndph.ox.ac.uk/showcase/label.cgi?id=220). We included only nonratio NMR measures in the current analysis.

Plasma neurobiomarkers were measured for a subset of participants (n = 1,268) who engaged in the first brain imaging visit (2014 and thereafter), including plasma Aβ40, Aβ42, GFAP, NEFL and pTau-181.

Age-related physiological phenotypes measured at baseline included self-rated health (poor versus others), usual walking speed, self-rated facial aging (older than you are versus others), tiredness and lethargy (nearly every day versus others), sleeplessness (usually versus others), hand grip strength (standardized by weight), systolic and diastolic blood pressure (average of multiple readings), body mass index, lung function (forced expiratory volume in 1 s standardized by height squared) and leukocyte telomere length (T/S ratio—ratio of the telomere repeat copy number (T) to the copy number of the single-copy gene HBB (S)—corrected for technical variation, log-transformed and z-standardized).

Cognition and mental well-being outcomes were measured at baseline and follow-up surveys using questionnaires. Cognitive function phenotypes included reaction time (a measure of processing speed, which is a component of general cognitive function), numerical memory (a measure of numerical short-term memory), fluid intelligence (a score that assesses crystallized and fluid intelligence in both verbal and numerical aspects) and visual memory (a measure of visuospatial working memory). These four tests demonstrated high validity and reliability74, as well as predictive ability for incident dementia in the UKB. Reaction time was available for all participants at baseline and was phenotypically and genetically related to general cognitive function, which was then used as a major cognitive function phenotype. The last three cognition measures were available for a subset of participants at baseline and were tested in the online follow-up surveys (2014 and thereafter and 2021 and thereafter). Mental health and well-being outcomes included the Patient Health Questionnaire 4 (PHQ-4), which measures the general symptoms of depression and anxiety; self-rated health at baseline; the PHQ-9, which measures the severity of depressive symptoms; the Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7 Scale (GAD-7), which measures generalized anxiety symptoms; self-harm behavior, including self-harm and suicidal ideation/behavior; mental distress; happiness; satisfaction with one’s own health; and self-rated health from the online follow-up survey. Other general health outcomes included self-rated health at baseline and imaging visits. Details of the online cognition and mental well-being survey are available online (https://biobank.ndph.ox.ac.uk/showcase/refer.cgi?id=2800).

Modifiable lifestyle factors included smoking, alcohol consumption, physical activity, sedentary time, sleep duration, intake of fruits and vegetables, intake of oily fish, intake of red meat and intake of processed meat. Detailed definitions and classifications of lifestyle factors are provided elsewhere75.

In the CKB, incident diseases and cause-specific mortality were ascertained through electronic linkage to national registries and health insurance records70. All disease diagnoses were coded using ICD-10, with baseline information kept blinded. Participants were followed until death, loss to follow-up (14.

In the NHS, deaths were ascertained through state vital records, the National Death Index, next of kin and postal authorities. Incident cases of cancer, myocardial infarction and stroke were initially self-reported on biennial questionnaires and subsequently confirmed through a physician review of medical records. Self-reported diagnoses of incident T2D were validated using a supplementary questionnaire. Dementia cases were identified based on physician-reviewed death records and biennial self-reported physician diagnoses of AD or other dementias.

Brain MRI data

All brain MRI data in the UKB were acquired using a 3-T Siemens Skyra scanner, preprocessed with quality control and summarized as image-derived phenotypes (IDPs). We used the data (n = 49,002) from the first brain imaging visit (2014 and thereafter). Details of image acquisition, processing, quality control and phenotype calculation are described in the online document (https://biobank.ctsu.ox.ac.uk/showcase/showcase/docs/brain_mri.pdf) and published work76. Tissue type and gray matter segmentation of magnetic resonance images was performed using FAST (FMRIB’s Automated Segmentation Tool), while subcortical structures were modeled using FIRST (FMRIB’s Integrated Registration and Segmentation Tool). The GMVs of 139 cortical, subcortical and cerebellar regions based on the Harvard–Oxford atlas and the Diedrichsen cerebellar atlas were then derived from T1-weighted MRI. The tWMH and microstructural measures of white matter tracts (fractional anisotropy, mean diffusivity, intracellular volume fraction, orientation dispersion and isotropic volume fraction) were derived from diffusion MRI. Other IDPs, such as total brain volume and subcortical volume, were also included. Extreme outliers (outside ±4 s.d.) that may reflect processing errors or brain abnormalities were excluded on a case-wise basis (

Polygenic risk score

PRSs were generated by the UKB using a Bayesian approach applied to summary statistics of external (ancestry-specific, when applicable) GWAS meta-analysis with no sample overlap with the UKB population, as described online (https://biobank.ndph.ox.ac.uk/showcase/refer.cgi?id=5202). We extracted PRSs for AD, PD, schizophrenia, MS and bipolar disorder.

Calculation of biological age gap and extreme ageotypes

Chronological age as a decimal value was calculated by taking the number of days between the baseline assessment date and the approximate birth date (based on the month and year of birth, with the first day of the birth month assigned as the birth date) and dividing that number by 365.25 in all three cohorts.

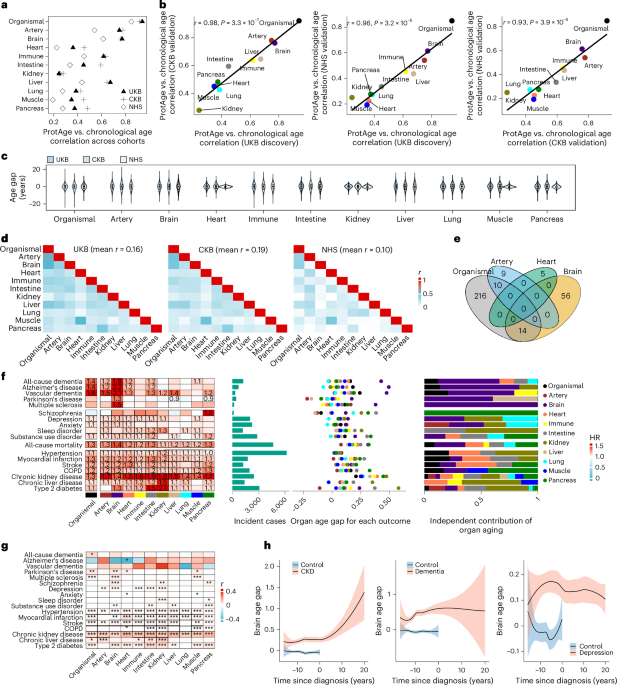

All eligible UKB participants (n = 43,616) were randomly split into training and testing sets with a 7:3 ratio. To identify APs and estimate proteomic age, we used the LightGBM77 model, which outperformed five other alternative machine learning models, including LASSO, Elastic Net and three artificial neural network architectures (multilayer perceptron, ResNet and TabR), in predicting overall organismal proteomic age (Supplementary Note 7)7. Sex-specific models for organismal aging showed high correlations with the overall model for both sexes (r = 0.99 and 0.98, respectively), supporting the use of combined-sex models to enhance the generalizability of findings.

In the UKB training set (n = 30,536), using LightGBM, we trained one organismal aging model based on all 2,916 proteins and ten organ-specific aging models based on the selected proteins enriched in the brain, heart, lung, immune system, artery, intestine, liver, muscle or pancreas (Supplementary Table 3). First, we tuned the model hyperparameters through fivefold cross-validation using the Optuna module in Python78. Across 200 trials, parameters were tested and optimized to maximize the average model R2 across all folds. Second, we performed Boruta feature selection using the shap-hypetune module, which randomly permutes all model features (referred to as shadow features, representing random noise)79 and helps distinguish the true signal from noise. Shadow features were generated at each iteration, and a model was trained using all features and the shadow features. Features were then evaluated based on their mean Shapley Additive Explanations (SHAP) values, a measure of feature importance. Features with absolute mean SHAP values lower than those of all random shadow features were removed. We conducted Boruta selection with 200 trials, setting a 100% threshold to compare shadow features and real features. Third, we retuned the model hyperparameters for a new model based on the selected protein subset, using the same procedure as above. Both tuned LightGBM models—before and after feature selection—were evaluated for overfitting and validated using fivefold cross-validation on the combined training set, followed by performance testing on the independent holdout test set. The holdout testing set was reserved during parameter tuning and feature selection and was used only for performance evaluation.

Based on the final trained model with Boruta-selected APs, we calculated organismal and organ-specific proteomic age for the full UKB sample (n = 43,616) using fivefold cross-validation. Within each fold, predicted age values were calculated by training a LightGBM model using the final hyperparameters, which were then aggregated across folds to generate the proteomic age for the full sample. Finally, based on proteomic age, we defined two aging phenotypes: age gap (the residual of proteomic age regressed on chronological age, reflecting accelerated or delayed aging compared to same-aged peers) and extreme ageotypes (a 1.5 s.d. increase or decrease in at least one organ age gap, reflecting individuals with extremely aged or youthful organs).

Given the prior knowledge that hundreds of proteins are related to organismal and organ aging3, we further refined the selection of associated proteins through RFE using SHAP. This process aims to identify the minimum number of proteins necessary for the accurate prediction of aging. In the RFE analysis, we started with the full set of APs identified by Boruta. We trained models using fivefold cross-validation on the training set and calculated the mean R2 and absolute SHAP values for each protein across the folds. We then iteratively eliminated the protein with the lowest SHAP value at each step and trained a new model until the final model included only one protein. We recalculated proteomic age and aging phenotypes based on the refined proteins using the same methods as described above, with the number of proteins determined by visual inspection of R2 following RFE. We compared the association of outcomes between the refined aging clock with decreasing number of proteins and the original clock that uses the full set of Boruta-selected proteins.

Proteomic organ age in the CKB and NHS was predicted using the trained UKB model (full or RFE-refined panel), and the organ age gap was calculated in these datasets following the same approach as in the UKB.

For comparison, we also measured biological age based on clinical traits using the validated KDM-biological age (KDM-BA)59 and PhenoAge58 algorithms, which predict the risk of death and morbidity. These aging measures were trained using data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey and projected onto the UKB data (Supplementary Note 8). PhenoAge was calculated based on albumin, alkaline phosphatase, C-reactive protein and glucose levels, along with lymphocyte proportion, mean cell volume, white blood cell count and red cell distribution width. The KDM-BA was calculated based on albumin, alkaline phosphatase, C-reactive protein, creatinine, glycated hemoglobin, total cholesterol, blood urea nitrogen and systolic blood pressure levels.

Missing data imputation

Missing values for all covariates, except age, in the UKB were imputed using the R package missRanger, which combines random forest imputation with predictive mean matching. Proteomic data were not imputed, leveraging the default capability of LightGBM to handle missing values. During model training, missing values for numerical features were assigned to the side of the ongoing split that yields the greatest reduction in loss, maximizing the information gain within the decision tree construction process without necessitating imputation. The imputation dataset comprised 100 baseline variables across multiple domains (physical health, environment and lifestyle) as predictors for imputation, excluding variables with nested response patterns. Responses of ‘do not know’ were treated as missing values (NA) and imputed. However, responses of ‘prefer not to answer’ were not imputed and were set to NA in the final analysis dataset. Study outcomes were not imputed. CKB and NHS data had no missing values for imputation.

Statistical analysis

Associations of age gap or extreme ageotypes (presence and number) across organ systems with incident diseases, multimorbidity and all-cause mortality in the UKB were assessed using Cox proportional hazards regression models, adjusting for age at recruitment, sex, ethnicity, education level, Townsend deprivation index, International Physical Activity Questionnaire activity group, smoking status and recruitment center. The follow-up period commenced from the date of baseline recruitment to the earliest date of disease diagnosis from the three data sources, the date of death, or the last available date provided by the hospital or general practitioner, whichever came first. Participants with a history of the corresponding outcome before the start of follow-up were excluded. The proportional hazards assumption was tested using Schoenfeld residuals, with no violations observed. The FDR calculated using the Benjamini–Hochberg method was applied to correct for multiple comparisons. Kaplan–Meier plots were generated to depict the cumulative incidence of outcomes over time. To further evaluate the potential clinical utility of organ aging clocks for risk stratification, we tested the association of organ age gaps in combination with other biomarkers using a multivariate Cox model, adjusting for the same covariates.

Associations of organ age gaps and biological aging acceleration (KDM-BA and PhenoAge gaps) with blood chemistry measures, blood counts, neurobiomarkers, age-related physiological conditions, cognition and mental well-being, NMR metabolites, and modifiable lifestyle factors were assessed using linear or logistic regression models, with adjustments for age, sex, education level, Townsend deprivation index, International Physical Activity Questionnaire activity group, smoking status and recruitment center, where applicable. P values were corrected for multiple comparisons using the FDR.

To test the role of the organ age gap in the transition of cognitive function and disease in the UKB, we assessed the association of organ age gaps with three sets of longitudinal changing patterns: (1) transition from cognitively normal at baseline (without NDs) to MCI at 12 years of follow-up. MCI at follow-up was defined as a global cognitive score 1.5 s.d. below the baseline mean of cognitively normal participants stratified by educational level80. (2) Transition from MCI at baseline to incident NDs at follow-up. MCI at baseline was defined as a global cognitive score 1.5 s.d. lower than the stratified baseline mean score. (3) Transition from psychological distress at baseline (without psychiatric disease) to incident psychiatric diseases at the follow-up. Psychological distress (subclinical symptoms of depression and anxiety) at baseline was defined as a PHQ-4 score of ≥6 (ref. 81). Baseline cognitive and mental health conditions were adjusted for in the Cox regression model.

Receiver operating characteristic curve analyses were conducted to compare the predictive performance of the proteomic aging clock to that of clinical and genetic biomarkers for disease and mortality, based on the logistic regression model. We tested the predictive performance of organ aging both independently and in combination with other measures, including cognitive function, PhenoAge and PRS (when applicable), while adjusting for basic demographic measures (age, sex and education). Differences in the AUC between models were assessed using bootstrap tests with 2,000 iterations.

External validation of the association of organ aging with diseases and death in the CKB and NHS was conducted using Cox regression models, as in the UKB. Models were adjusted for age, sex, ethnicity, education, study region, smoking and physical activity in the CKB. In the NHS, models were adjusted for age, ethnicity, neighborhood socioeconomic status, smoking and physical activity. To account for potential bias from the case–control design, analyses were performed on both the full and control samples, with cross-cohort comparisons based on estimates from the control groups of the CKB and NHS.

All analyses and data visualizations were conducted using R (v.4.2) and Python (v.3.6).

Genotyping, genome-wide association analysis and annotation

DNA extraction, genotyping and initial quality control of the genomic data in the UKB have been detailed elsewhere67. Briefly, 488,377 participants were genotyped using two similar genotyping arrays (UK BiLEVE and UKB Axiom Array), and data were imputed using the UK10K reference panel, the 1000 Genomes phase 3 panel and the Haplotype Reference Consortium panel. The GWAS on the proteomic aging clock was conducted using REGENIE, which better accounts for potential population stratification and family relatedness82. The regression models were adjusted for age, sex, genetic batch and the first ten genetic PCs. Data were filtered to include SNPs with a minor allele frequency of >1%, a minor allele count of ≥20, an imputation quality INFO score of >0.1 and a Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium value of ≥1 × 10−15 for participants with available proteomic data. To further account for population stratification, the current analysis was restricted to participants of European ancestry, as confirmed by the PCs of the genotyped variants.

GWAS summary results were then mapped and annotated using the SNP2GENE module in FUMA v1.5.2. A precalculated linkage disequilibrium structure based on the 1000 Genomes European reference population was used. Independent significant SNPs (P −8 and r2 r2

Gene-based association analysis was conducted using MAGMA. SNPs were mapped to 19,839 protein-coding genes (0-kb window). Gene-based P values were calculated using an SNP-wide mean model, with 1000 Genomes phase 3 used as a reference panel. Bonferroni correction was applied to correct for multiple testing (P = 0.05/19,839). MAGMA tissue enrichment analysis was then conducted for related genes using gene expression data from 30 general tissues in GTEx v8. Based on these expression data, differentially expressed gene sets were created, and the prioritized genes were tested against these sets to determine whether the genes were upregulated or downregulated in a specific tissue compared to others. Finally, to test the overrepresentation of biological functions, the prioritized genes were evaluated against predefined gene sets such as MSigDB (Molecular Signatures Database), WikiPathways and GWAS Catalog-reported genes.

Functional enrichment and protein–protein interaction

Functional enrichment analysis based on Gene Ontology (GO) biological processes, GO molecular functions and KEGG (Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes) pathways was performed using all human genes as the background distribution. Enrichment was assessed using the hypergeometric test, and P values were adjusted for multiple testing using the Benjamini–Hochberg method. Sensitivity analyses were conducted using only proteins included in the Olink Explore platform as the statistical background. Protein–protein interaction networks were generated using the STRING database83.

Single-cell and bulk RNA sequencing

Preprocessed human scRNA-seq data for the brain40 and peripheral vasculature45 were accessed from studies in the Human Cell Atlas (https://cellxgene.cziscience.com/gene-expression). Preprocessed human scRNA-seq data for the brain vasculature were accessed from ref. 44. Gene expression count data were log(transcripts per million + 1)-transformed and z-scored for visualization. Differential expression data of RNA and proteins between AD and control cases were obtained from ref. 84

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.